Rachel Yoder at Harper’s Magazine:

What the old Amish woman named Rachel Smoker and others like her practice is called, depending on whom you ask, powwow or Braucherei or pulling pain or active prayer or witchcraft or folk-cultural religious ritual, though Rachel Smoker would never call it any of these things. She prefers “natural healing” and “reflexology.”

What the old Amish woman named Rachel Smoker and others like her practice is called, depending on whom you ask, powwow or Braucherei or pulling pain or active prayer or witchcraft or folk-cultural religious ritual, though Rachel Smoker would never call it any of these things. She prefers “natural healing” and “reflexology.”

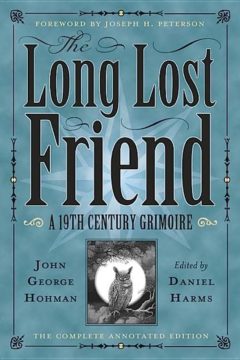

I came to find her because of a book of spells. And I sought out this book because it seemed to me one of the more compelling corners of my Amish and Mennonite heritage, though it had never once been mentioned to me growing up. The book—The Long Lost Friend: A Collection of Mysterious and Invaluable Arts and Remedies, also called the “Famous Witchbook of the Pennsylvania Dutch”—was compiled in the early nineteenth century by John George Hohman, a German-speaking immigrant.

more here.

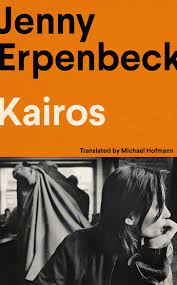

How is a totalitarian state like a love affair? They both leave archives behind when they go. How is a totalitarian state like a bad love affair? The archive that survives the end of each is a monument to abuse, surveillance and betrayal.

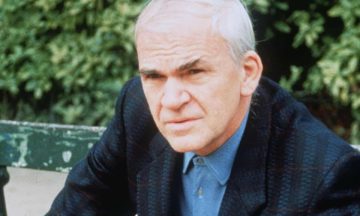

How is a totalitarian state like a love affair? They both leave archives behind when they go. How is a totalitarian state like a bad love affair? The archive that survives the end of each is a monument to abuse, surveillance and betrayal. For a long time before his death this week at the age of 94, the novelist Milan Kundera seemed to have fallen out of fashion with critics. Jonathan Coe wrote of his “problematic sexual politics” with their “ripples of disquiet.” Alex Preston complained about the “adolescent and posturing” flavour of the books which had thrilled him in his youth, adding of Kundera’s later novels that reading them was an “increasingly laboured process of digging out the occasional gems from the abstraction and tub-thumping philosophising… a series of retreats into mere cleverness.” Diane Johnson of the New York Times seemed to ring the death knell loudest: “what he has to tell us seems to have less relevance… the world has run beyond some of the concerns that still preoccupy him.”

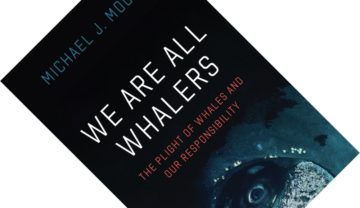

For a long time before his death this week at the age of 94, the novelist Milan Kundera seemed to have fallen out of fashion with critics. Jonathan Coe wrote of his “problematic sexual politics” with their “ripples of disquiet.” Alex Preston complained about the “adolescent and posturing” flavour of the books which had thrilled him in his youth, adding of Kundera’s later novels that reading them was an “increasingly laboured process of digging out the occasional gems from the abstraction and tub-thumping philosophising… a series of retreats into mere cleverness.” Diane Johnson of the New York Times seemed to ring the death knell loudest: “what he has to tell us seems to have less relevance… the world has run beyond some of the concerns that still preoccupy him.” We Are All Whalers is veterinary scientist Michael J. Moore’s account of a life spent studying different whale species and what is killing them. He argues that anyone participating in our global economy has blood on their hands, often without realising it. Readers are warned that this book does not avoid graphic details. His research has ultimately drawn him to the problems of whales getting entangled in fishing gear and being struck by ships. However, it is the path that took him there, through both industrial and subsistence whaling, that might leave some readers more upset.

We Are All Whalers is veterinary scientist Michael J. Moore’s account of a life spent studying different whale species and what is killing them. He argues that anyone participating in our global economy has blood on their hands, often without realising it. Readers are warned that this book does not avoid graphic details. His research has ultimately drawn him to the problems of whales getting entangled in fishing gear and being struck by ships. However, it is the path that took him there, through both industrial and subsistence whaling, that might leave some readers more upset. Major economies are on the “cusp of an AI revolution” that could trigger job losses in skilled professions such as law, medicine and finance, according to an influential international organisation.

Major economies are on the “cusp of an AI revolution” that could trigger job losses in skilled professions such as law, medicine and finance, according to an influential international organisation. Czech writer

Czech writer  There are a handful of topics that I almost force myself to not think about because the thoughts lead to a dead end. At the top of that list is climate change. It’s one of those problems that starts to overwhelm me when I consider the scale and the implications and all the barriers to tackling it.

There are a handful of topics that I almost force myself to not think about because the thoughts lead to a dead end. At the top of that list is climate change. It’s one of those problems that starts to overwhelm me when I consider the scale and the implications and all the barriers to tackling it. The Maharaja of Whereverstan sends his daughter to Harvard so that she appears meritorious. In exchange, Harvard gets the credibility boost of being the place the Maharaja of Whereverstan sent his daughter. And Harvard’s other students get the advantage of networking with the Princess Of Whereverstan. Twenty years later, when one of them is an oil executive and Whereverstan is handing out oil contracts, she puts in a word with her old college buddy the Princess and gets the deal. It’s obvious what the oil executive has gotten out of this, but what does the Princess get? I think she gets the right to say she went to Harvard, an honor which is known to go mostly to the meritorious.

The Maharaja of Whereverstan sends his daughter to Harvard so that she appears meritorious. In exchange, Harvard gets the credibility boost of being the place the Maharaja of Whereverstan sent his daughter. And Harvard’s other students get the advantage of networking with the Princess Of Whereverstan. Twenty years later, when one of them is an oil executive and Whereverstan is handing out oil contracts, she puts in a word with her old college buddy the Princess and gets the deal. It’s obvious what the oil executive has gotten out of this, but what does the Princess get? I think she gets the right to say she went to Harvard, an honor which is known to go mostly to the meritorious. In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it.

In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it. CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry. The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence?

The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence? In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”

In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”