Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Grant Sanderson: Why Laplace transforms are so useful

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Notes On Joni Mitchell

Rick Moody at Salamgundi:

1. The day on which we embarked to see Joni Mitchell play the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles (“we” defined as myself, my wife Laurel Nakadate, and our son Theo), having flown west from Boston, was the date of my own parents’ wedding anniversary, namely, October 19.

2. My parents had been divorced since, I think, 1971, or 53 years, on the occasion of the concert. I still think of them on October 19.

3. Is not divorce, any divorce, on the list of “petty wars” that the Joni Mitchell narrator of “Traveller (Hejira)” describes in that bit of song ravishment? (I’m using the demo/early version here.)

4. There are things I find keenly uncomfortable about Los Angeles. I like to walk, but L.A., because of its scale, requires a lot of driving. A constancy of highway transit, yes. A city of travelers.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Modeling the geopolitics of AI development

Alex Amadori, Gabriel Alfour, Andrea Miotti, and Eva Behrens at AI Scenarios:

We model national strategies and geopolitical outcomes under differing assumptions about AI development. We put particular focus on scenarios with rapid progress that enables highly automated AI R&D and provides substantial military capabilities.

Under non-cooperative assumptions—concretely, if international coordination mechanisms capable of preventing the development of dangerous AI capabilities are not established—superpowers are likely to engage in a race for AI systems offering an overwhelming strategic advantage over all other actors.

If such systems prove feasible, this dynamic leads to one of three outcomes:

- One superpower achieves an unchallengeable global dominance;

- Trailing superpowers facing imminent defeat launch a preventive or preemptive attack, sparking conflict among major powers;

- Loss-of-control of powerful AI systems leads to catastrophic outcomes such as human extinction.

Middle powers, lacking both the muscle to compete in an AI race and to deter AI development through unilateral pressure, find their security entirely dependent on factors outside their control: a superpower must prevail in the race without triggering devastating conflict, successfully navigate loss-of-control risks, and subsequently respect the middle power’s sovereignty despite possessing overwhelming power to do otherwise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Giorgio Agamben And “Inoperativity”

Adam Kirsch at the NYRB:

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz.

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz.

Born in Rome in 1942, Agamben began his career in the 1970s and 1980s as what Adam Kotsko, who has translated many of his books into English, calls “a hermetic aesthetic thinker” mainly interested in problems of language. But starting with the publication of his book Homo Sacer in 1995 he became, Kotsko writes, “one of the foremost political minds of our era.” In nine densely argued and dizzyingly erudite books published over the next two decades, Agamben investigated the concepts of law, sovereignty, and power in the Western political tradition.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Lanterns

The summer we placed my mother in the psychiatric hospital,

the July sunlight spray-painted itself as glare along the building’s walls

as we drove away. I peered out the back window while our father

told us that our mother’s thoughts had strayed deep into the woods

and had lost their way, though the doctors had lanterns to help her

find her way back out. Years later, I imagined my mother was a mystic,

that her fever dreams that summer were whispering deeper truths,

that the mechanical thump of her heart was a secret numerology.

She told me once she was grateful for the lights of the nightly stars,

that they were trying to be gardens. And she told me once that

the years were like fingertips brushing lightly across the surface

of some imagined drum, and that naming something was forever

a way of sending it into exile, banishing it to its own separate sphere,

landlocked and lonely. And once—after our father divorced her—

he described how, in his childhood summers in Michigan’s

Upper Peninsula, turkey vultures with blood-red heads had circled

above the roadkill as he rode his bike to school, as though

a death watch were a form of sleepy hypnosis. Not one of us, I think,

is fully part of this world but lives inside the body’s ossuary.

We are three parts dreaming and two parts disappointment.

I remember listening to an argument once between my father

and my brother about statutes of limitations over his treatment

of our mother. That was maybe a year before his death,

and our father grew quieter and more patient than usual

while a blur of morning light fell through the windows

and transformed one half of his body into a smudge of photons,

the words pummeling him into something almost incorporeal.

My mother had once claimed she’d been wintering all her life,

and I remembered her standing one January in our backyard,

coatless in the snow, in bare feet, huddling her arms

around her body like a junco motionless on a power line,

gazing toward the bright bruise of sun.

by Doug Ramspeck

from Rattle Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Szalay’s ‘Flesh’ Wins 2025 Booker Prize

Alex Marshall in The Guardian:

When David Szalay’s novel “All That Man Is” was nominated for the 2016 Booker Prize, the author described the award ceremony as “a horrible experience.” He sat through a “very stressful” dinner, wondering whether his book would triumph, only for it to lose to Paul Beatty’s “The Sellout.” He later told The Guardian newspaper, “Only trauma imprints memories that clearly.”

When David Szalay’s novel “All That Man Is” was nominated for the 2016 Booker Prize, the author described the award ceremony as “a horrible experience.” He sat through a “very stressful” dinner, wondering whether his book would triumph, only for it to lose to Paul Beatty’s “The Sellout.” He later told The Guardian newspaper, “Only trauma imprints memories that clearly.”

On Monday night in London, Szalay sat through another Booker Prize dinner. But this time his latest novel, “Flesh,” won the prestigious literary award. The author Roddy Doyle, who chaired this year’s judging panel, called it a “singular” and “extraordinary” novel. “It’s just not like any other book,” Doyle told a news conference before Monday’s announcement about the novel, in which Istvan, a lonely Hungarian teenager, makes an unexpected rise to the height of British society. The sparseness of Szalay’s writing compels readers to “climb into the novel and be involved,” Doyle added.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Humans Didn’t Invent Mathematics, It’s What the World Is Made Of

Sam Baron in The Singularity Hub:

Bees in hives produce hexagonal honeycomb. Why? According to the “honeycomb conjecture” in mathematics, hexagons are the most efficient shape for tiling the plane. If you want to fully cover a surface using tiles of a uniform shape and size while keeping the total length of the perimeter to a minimum, hexagons are the shape to use. Charles Darwin reasoned that bees have evolved to use this shape because it produces the largest cells to store honey for the smallest input of energy to produce wax. The honeycomb conjecture was first proposed in ancient times, but was only proved in 1999 by mathematician Thomas Hales.

Bees in hives produce hexagonal honeycomb. Why? According to the “honeycomb conjecture” in mathematics, hexagons are the most efficient shape for tiling the plane. If you want to fully cover a surface using tiles of a uniform shape and size while keeping the total length of the perimeter to a minimum, hexagons are the shape to use. Charles Darwin reasoned that bees have evolved to use this shape because it produces the largest cells to store honey for the smallest input of energy to produce wax. The honeycomb conjecture was first proposed in ancient times, but was only proved in 1999 by mathematician Thomas Hales.

Here’s another example. There are two subspecies of North American periodical cicadas that live most of their lives in the ground. Then, every 13 or 17 years (depending on the subspecies), the cicadas emerge in great swarms for a period of around two weeks. Why is it 13 and 17 years? Why not 12 and 14? Or 16 and 18? One explanation appeals to the fact that 13 and 17 are prime numbers. Imagine the cicadas have a range of predators that also spend most of their lives in the ground. The cicadas need to come out of the ground when their predators are lying dormant.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, November 12, 2025

‘Flesh’ wins 2025 Booker Prize: ‘We had never read anything quite like it’

Andrew Limbong at NPR:

István isn’t one of the most talkative characters in literary fiction. He says “yeah” and “okay” a lot, and is mostly reactive to the world around him. But that quietness covers up a tumultuous life — from Hungary to England, from poverty to being in close contact with the super-rich.

István isn’t one of the most talkative characters in literary fiction. He says “yeah” and “okay” a lot, and is mostly reactive to the world around him. But that quietness covers up a tumultuous life — from Hungary to England, from poverty to being in close contact with the super-rich.

He’s the center of David Szalay’s latest novel, Flesh, which just won this year’s Booker Prize. “We had never read anything quite like it,” said Roddy Doyle, chair of this year’s prize, in a statement announcing the win. “I don’t think I’ve read a novel that uses the white space on the page so well. It’s as if the author, David Szalay, is inviting the reader to fill the space, to observe — almost to create — the character with him.”

The Booker Prize is one of the most prestigious awards in literature. It honors the best English-language novels published in the U.K. Winners of the awards receive £50,000, and usually a decent bump in sales.

Szalay is a Hungarian-British author. Flesh is his sixth novel.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

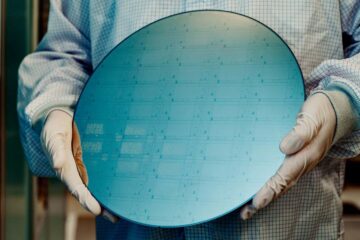

IBM has unveiled two unprecedentedly complex quantum computers

Karmela Padavic-Callaghan in Nature:

As a contender in the race to build an error-free quantum supercomputer, IBM has been taking a different tack than its most direct competitors. Now, the firm has unveiled two new quantum computers, called Nighthawk and Loon, that may validate its approach and could provide innovations needed to make the next generation of these devices truly useful.

As a contender in the race to build an error-free quantum supercomputer, IBM has been taking a different tack than its most direct competitors. Now, the firm has unveiled two new quantum computers, called Nighthawk and Loon, that may validate its approach and could provide innovations needed to make the next generation of these devices truly useful.

IBM’s quantum supercomputer design is modular and relies on developing new ways to connect superconducting qubits within and across different quantum computer units. When the firm first debuted it, some researchers questioned the practicality of these connections, says Jay Gambetta at IBM. He says it was as if people were saying to the IBM team: “‘You’re in theory land, you cannot realise that.’ And [now] we’re going to show that [to be] wrong.”

Within Loon, each qubit is connected to six others and those connections can “break the plane”, which means they don’t just travel across a chip but can move vertically as well, a capability that no other superconducting quantum computer has had so far.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Geoffrey Hinton: What Is Understanding?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Amitav Ghosh: How visions of catastrophe shape the ‘climate solutions’ imposed by aid agencies

Amitav Ghosh at Equator:

I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids.

I came of age as a reader in the 1970s, when apocalyptic fiction was much in vogue because of intensifying nuclear anxieties. As a teenager, I devoured books set in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe, like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids.

Apocalyptic fiction was then more or less exclusively the preserve of Western writers: as far as I know, no Indian novels of this kind existed at that time. Perhaps this was because we, in India, did not have nuclear weapons targeted directly at us back then; we were merely spectators in a conflict that had two blocs of powerful nations as its main protagonists. In the event of a nuclear war, we would be merely collateral damage; our elimination would be an afterthought.

Today the risk of nuclear war is greater than ever before, yet it hardly merits so much as a headline. This is possibly because the world as we know it could now be brought to an end in many other ways as well – for instance, through biodiversity loss, runaway artificial intelligence, unstoppable viruses and, of course, abrupt climate change.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Romantic Revolution in Politics & Morals – Isaiah Berlin

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Are All Animals Of Moral Concern?

Jeff Sebo at Aeon Magazine:

You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s essay ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ (1972), raises big questions. Are ants sentient – able to experience pleasure and pain? Do they deserve moral concern? Should you take a moment out of your day to help one out?

You notice an ant struggling in a puddle of water. Their legs thrash as they fight to stay afloat. You could walk past, or you could take a moment to tip a leaf or a twig into the puddle, giving them a chance to climb out. The choice may feel trivial. And yet this small encounter, which resembles the ‘drowning child’ case from Peter Singer’s essay ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ (1972), raises big questions. Are ants sentient – able to experience pleasure and pain? Do they deserve moral concern? Should you take a moment out of your day to help one out?

Historically, people have had very different views about such questions. Exclusionary views – dominant in much of 20th-century Western science – err on the side of denying animals sentience and moral status. On this view, only mammals, birds and other animals with strong similarities to humans merit moral concern. Attributions of sentience and moral status require strong evidence. Human exceptionalist perspectives reinforced this view as well, holding that other animals were created for human use.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Are we doomed?

David Runciman in London Review of Books:

People are living longer than they used to. They are also having fewer children. The evidence of what this combination can do to a society is growing around the world, but some of the most striking stories come from Japan. For decades the Japanese health ministry has released an annual tally of citizens aged one hundred or over. This year the number of centenarians reached very nearly a hundred thousand. When the survey started in 1963, there were just 153. In 1981 there were a thousand; in 1998 ten thousand. Japan now produces more nappies for incontinent adults than for infants. There is a burgeoning industry for the cleaning and fumigating of apartments in which elderly Japanese citizens have died and been left undiscovered for weeks, months or years. Older people have far fewer younger people to take care of them or even to notice their non-existence. That neglect is a brute function of some simple maths.

People are living longer than they used to. They are also having fewer children. The evidence of what this combination can do to a society is growing around the world, but some of the most striking stories come from Japan. For decades the Japanese health ministry has released an annual tally of citizens aged one hundred or over. This year the number of centenarians reached very nearly a hundred thousand. When the survey started in 1963, there were just 153. In 1981 there were a thousand; in 1998 ten thousand. Japan now produces more nappies for incontinent adults than for infants. There is a burgeoning industry for the cleaning and fumigating of apartments in which elderly Japanese citizens have died and been left undiscovered for weeks, months or years. Older people have far fewer younger people to take care of them or even to notice their non-existence. That neglect is a brute function of some simple maths.

In 1950, Japan had a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 4, which represents the average number of children a woman might expect to have in her lifetime. Continued over five generations, that would mean a ratio of 256 great-great-grandchildren to every sixteen great-great-grandparents – in other words, each hundred-year-old might have sixteen direct descendants competing to look after them. Today Japan’s TFR is approaching 1: one child per woman (or one per couple, half a child each). That pattern continued over five generations means that each solitary infant has as many as sixteen great-great-grandparents vying for his or her attention. Within a century the pyramid of human obligation has been turned on its head.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cell-Electronic Hybrid Chips Could Enable Surgery-Free Brain Implants

RJ Mackenzie in The Scientist:

Brain implants can provide important insights into the nervous system and even relieve the symptoms of brain diseases. But getting implants into a patient’s head is an operation fraught with risks of tissue damage and infection.

Brain implants can provide important insights into the nervous system and even relieve the symptoms of brain diseases. But getting implants into a patient’s head is an operation fraught with risks of tissue damage and infection.

Some approaches use blood vessels to deliver implants to the fringes of the brain, but these cannot access deep-lying areas at the roots of some of the most stubborn brain disorders. To overcome this, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led by bioengineer Deblina Sarkar, took up the challenge of designing an implant with minimal footprint and maximum efficacy. In a new paper, published in Nature Biotechnology, Sarkar and her colleagues unveiled a novel implant design approach which piggybacks subcellular electronic devices to circulating immune cells. 1 The team’s wireless electronic-cell hybrids, which are powered by light, are 10 micrometers in diameter, which is smaller than a single droplet of mist. The researchers found that these devices could migrate to areas of inflammation in the mouse brain and then stimulate brain tissue with micrometer-level precision. They called their hybrids the first in a new field of “circulatronic” devices.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

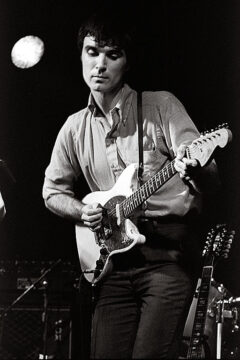

David Byrne’s Career of Earnest Alienation

Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.)

If you spend enough time wandering around downtown Manhattan, the odds are that you’ll eventually encounter the musician David Byrne riding a bicycle. (He owns four: a folding bike, an electric, an eight-speed, and a single-speed, which he recently lent to the pop singer Lorde.) One day this past June, pedalling alongside Byrne from his apartment in Chelsea to the Governors Island ferry, I watched at least a dozen New Yorkers clock his profile, whipping around to squint, softly pinching the arm of their companion and whispering, “Was that . . . ?” By then, Byrne was gone, a tuft of white hair whizzing toward the horizon. Spotting Byrne on two wheels has become a New York City rite of passage, like sussing out the best halal cart in midtown, or dropping something important onto the subway tracks. During the few months that Byrne and I spent together, I never saw him traverse the city via any other mode of transportation, even when the heat index was approaching hellscape and he was overdue for a meeting in Brooklyn. He simply reapplied sunscreen and pushed off. In 2023, he rode a custom white Budnitz single-speed directly onto the red carpet at the Met Gala while wearing a cream-colored turtleneck under a bespoke white suit by Martin Greenfield Clothiers. (The bike featured a belt drive, which prevented chain grease from smearing his pants; he had placed his parking placard for the gala in the basket.) In 2019, Byrne rode a bicycle onstage at the “Tonight Show” while promoting “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” a Broadway production that he wrote and starred in that year. (In 2020, it became a film, directed by Spike Lee.)

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

On a Squirrel Crossing the Road

in Autumn, In New England

It is what he does not know,

Crossing the road under the elm trees,

About the mechanism of my car,

About the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

About Mozart, India, Arcturus,

That wins my praise. I engage

At once in whirling squirrel-praise.

He obeys the orders of nature

Without knowing them.

It is what he does not know

That makes him beautiful.

Such a knot of little purposeful nature!

I who can see him as he cannot see himself

Repose in the ignorance that is his blessing.

It is what man does not know of God

Composes the visible poem of the world.

. . . Just missed him!

by Richard Eberhart

from Poet’s Choice

Time Life Books 1962

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, November 11, 2025

Tom Cat: On duality, detachment, and life and death decisions

Jennifer Thuy Vi Nguyen at Longreads:

When I arrived in Harlem, I felt anguished responsibility and resentment toward the cat. He could die, I perseverated. I had imagined Manhattan from the vantage point of a twenty-something with her lover, but was now relegated to “indoor New York lesbian with dying cat.” I searched his litter for pee and poop, as though playing a weird Where’s Waldo? Tom needed anti-anxiety medication with his wet food, and I was careful with the timing and dosage. I bypassed New York City nightlife to keep the cat alive.

When I arrived in Harlem, I felt anguished responsibility and resentment toward the cat. He could die, I perseverated. I had imagined Manhattan from the vantage point of a twenty-something with her lover, but was now relegated to “indoor New York lesbian with dying cat.” I searched his litter for pee and poop, as though playing a weird Where’s Waldo? Tom needed anti-anxiety medication with his wet food, and I was careful with the timing and dosage. I bypassed New York City nightlife to keep the cat alive.

Despite my worries as a feline caretaker, Tom displayed what I have since learned are normal cat behaviors. He stared out the living room window overlooking the Harlem River with longing and disdain. He walked across my keyboard with apathetic audacity. One moment he would lay like a cherub, the next he would reach for a feather toy attached to a string. He protracted and retracted his claws with a bored cadence, as if to say, I’m a cat and this shit is just what I do.

I oscillated between wondering whether Tom was fighting to live or actively trying to die.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

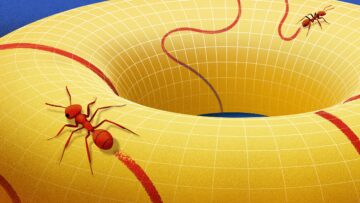

What Is a Manifold?

Paulina Rowińska in Quanta:

Standing in the middle of a field, we can easily forget that we live on a round planet. We’re so small in comparison to the Earth that from our point of view, it looks flat.

Standing in the middle of a field, we can easily forget that we live on a round planet. We’re so small in comparison to the Earth that from our point of view, it looks flat.

The world is full of such shapes — ones that look flat to an ant living on them, even though they might have a more complicated global structure. Mathematicians call these shapes manifolds. Introduced by Bernhard Riemann in the mid-19th century, manifolds transformed how mathematicians think about space. It was no longer just a physical setting for other mathematical objects, but rather an abstract, well-defined object worth studying in its own right.

This new perspective allowed mathematicians to rigorously explore higher-dimensional spaces — leading to the birth of modern topology, a field dedicated to the study of mathematical spaces like manifolds. Manifolds have also come to occupy a central role in fields such as geometry, dynamical systems, data analysis and physics.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.