Vybarr Cregan-Reid in Anthropocene:

Why are there no chairs in the King James Bible, or in all 30,000 lines of Homer? Neither are there any in Shakespeare’s Hamlet—written in 1599. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, it is a completely different story. Charles Dickens’s Bleak House suddenly has 187 of them. What changed? With sitting being called “the new smoking,” we all know that spending too much time in chairs is bad for us. Not only are they unhealthy, but like air pollution, they are becoming almost impossible for modern humans to avoid.

Why are there no chairs in the King James Bible, or in all 30,000 lines of Homer? Neither are there any in Shakespeare’s Hamlet—written in 1599. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, it is a completely different story. Charles Dickens’s Bleak House suddenly has 187 of them. What changed? With sitting being called “the new smoking,” we all know that spending too much time in chairs is bad for us. Not only are they unhealthy, but like air pollution, they are becoming almost impossible for modern humans to avoid.

When I started researching my book about how the world we have made is changing our bodies, I was surprised to discover just how rare chairs used to be. Now they’re everywhere: offices, trains, cafés, restaurants, pubs, cars, trains, concert halls, cinemas, doctors’ surgeries, hospitals, theaters, schools, university lecture halls, and all over our houses. (I guarantee you have more than you think.)

More here.

Scientists have created a neural network with the human-like ability to make generalizations about language

Scientists have created a neural network with the human-like ability to make generalizations about language W

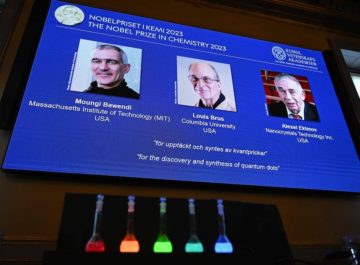

W When you were working at Bell Labs in the 1980s and discovered quantum dots, it was something of an accident. You were studying solutions of semiconductor particles. And when you aimed lasers at these solutions, called colloids, you noticed that the colors they emitted were not constant.

When you were working at Bell Labs in the 1980s and discovered quantum dots, it was something of an accident. You were studying solutions of semiconductor particles. And when you aimed lasers at these solutions, called colloids, you noticed that the colors they emitted were not constant. Yascha Mounk: I admire you as a writer, but there’s one book of yours that I sort of stumbled across again recently which I found to be deeply insightful and also personally meaningful, and that is The Happiness Curve.

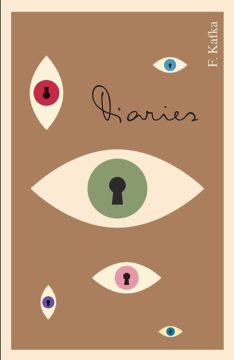

Yascha Mounk: I admire you as a writer, but there’s one book of yours that I sort of stumbled across again recently which I found to be deeply insightful and also personally meaningful, and that is The Happiness Curve. Franz Kafka was a champion of defeat, but he was also critically alive in the struggle to become himself. A prolific writer, he is thought to have burned or otherwise destroyed much of his own production. When he knew he was dying of tuberculosis, he asked his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to burn the rest, excluding only the short stories that had already been published and had established his growing reputation. We can be grateful that Brod disobeyed his friend and saw to the publication of the unfinished novels, The Missing Person (as Amerika), The Trial, and The Castle. These books and assorted stories and fragments established Kafka posthumously as a singular genius, not only a great modernist, but a writer who transcended his time, dramatizing psychic battles between individuals and the savage powers of family, law, and the state. These are the very nets that Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus had wanted to fly past, and found he could not. Kafka’s fictions are not allegories, but dreams. Their absurdist logic is absolute and insane, sometimes hilarious, more often nightmarish. Yet they seem true to the world. Only a breathtakingly original artist could have devised them.

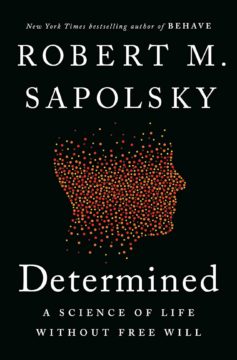

Franz Kafka was a champion of defeat, but he was also critically alive in the struggle to become himself. A prolific writer, he is thought to have burned or otherwise destroyed much of his own production. When he knew he was dying of tuberculosis, he asked his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to burn the rest, excluding only the short stories that had already been published and had established his growing reputation. We can be grateful that Brod disobeyed his friend and saw to the publication of the unfinished novels, The Missing Person (as Amerika), The Trial, and The Castle. These books and assorted stories and fragments established Kafka posthumously as a singular genius, not only a great modernist, but a writer who transcended his time, dramatizing psychic battles between individuals and the savage powers of family, law, and the state. These are the very nets that Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus had wanted to fly past, and found he could not. Kafka’s fictions are not allegories, but dreams. Their absurdist logic is absolute and insane, sometimes hilarious, more often nightmarish. Yet they seem true to the world. Only a breathtakingly original artist could have devised them. JULIEN CROCKETT: Most of the discoveries you reference in Determined are from the last 50 years, and half are from the last five, pointing towards a recent shift in biology and related fields. How has the answer to the fundamental question in biology—what is life?—changed during your career?

JULIEN CROCKETT: Most of the discoveries you reference in Determined are from the last 50 years, and half are from the last five, pointing towards a recent shift in biology and related fields. How has the answer to the fundamental question in biology—what is life?—changed during your career? Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and contributes to 15 percent of all cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. Though 20–30 percent of patients with early-stage breast cancers eventually develop

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and contributes to 15 percent of all cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. Though 20–30 percent of patients with early-stage breast cancers eventually develop  T

T Whoever governs America, dysfunctionally or not, speculating about a post-American world, is a waste of time. And there a few key areas of global affairs in which American institutions today play a crucial organizational role. I have written often in this newsletter about the

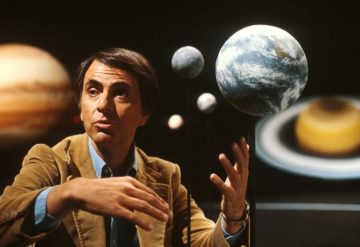

Whoever governs America, dysfunctionally or not, speculating about a post-American world, is a waste of time. And there a few key areas of global affairs in which American institutions today play a crucial organizational role. I have written often in this newsletter about the  Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote.

Early in 1993, a manuscript landed in the Nature offices announcing the results of an unusual — even audacious — experiment. The investigators, led by planetary scientist and broadcaster Carl Sagan, had searched for evidence of life on Earth that could be detected from space. The results, published 30 years ago this week, were “strongly suggestive” that the planet did indeed host life. “These observations constitute a control experiment for the search for extraterrestrial life by modern interplanetary spacecraft,” the team wrote. The acclaimed British philosopher

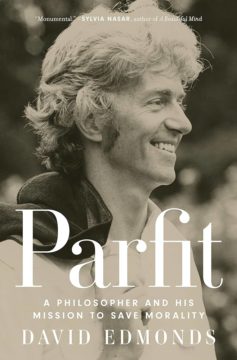

The acclaimed British philosopher  The subtitle of David Edmonds’s biography of the English philosopher Derek Parfit (1942-2017) is liable to raise more than a few eyebrows. Surely a mission to save morality is something only a God-like being could take on. And since God is dead, or rather has ceased to be believable, the prospect of rescuing morality must have vanished too. So is the subtitle to suggest that Parfit really was blessed with superhuman powers? Or are we to read it ironically, perhaps as a satirical comment on one philosopher’s exaggerated view of his own importance?

The subtitle of David Edmonds’s biography of the English philosopher Derek Parfit (1942-2017) is liable to raise more than a few eyebrows. Surely a mission to save morality is something only a God-like being could take on. And since God is dead, or rather has ceased to be believable, the prospect of rescuing morality must have vanished too. So is the subtitle to suggest that Parfit really was blessed with superhuman powers? Or are we to read it ironically, perhaps as a satirical comment on one philosopher’s exaggerated view of his own importance? Invisible Cities is built like a Boolean Truth Table. The mathematical table shows all possible combinations of inputs, and for each combination the output that the circuit will produce. It’s a logic operation. The categories we find in Invisible Cities – Hidden Cities, Cities and Desire, Cities and Memory, Thin Cities, Dead Cities, and so on – aren’t random. Once chosen, these “inputs” will reveal their “outputs”. Think of a Truth Table as including a column for each variable in the expression and a row for each possible combination of truth values (or cities in our case). Then add a column that shows the outcome of each set of values. That’s the dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan.

Invisible Cities is built like a Boolean Truth Table. The mathematical table shows all possible combinations of inputs, and for each combination the output that the circuit will produce. It’s a logic operation. The categories we find in Invisible Cities – Hidden Cities, Cities and Desire, Cities and Memory, Thin Cities, Dead Cities, and so on – aren’t random. Once chosen, these “inputs” will reveal their “outputs”. Think of a Truth Table as including a column for each variable in the expression and a row for each possible combination of truth values (or cities in our case). Then add a column that shows the outcome of each set of values. That’s the dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan.