Yagnishsing Dawoor in The Guardian:

The Bengali-American writer Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection is an urgent and affecting portrait of Rome in nine stories featuring characters, both native and non-native, who inhabit the city without ever feeling fully at home. As one remarks, “Rome switches between heaven and hell.” Like Whereabouts, Lahiri’s previous book, this collection was composed in Italian and then translated into English. Lahiri self-translated six out of the nine stories, entrusting editor Todd Portnowitz with the remaining three. The translation is supple and elegant throughout; sentences gleam and flow, adding to the vividness and immediacy of these tales about buried grief, belonging and unbelonging, the meaning of home and the cost of exile.

The Bengali-American writer Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection is an urgent and affecting portrait of Rome in nine stories featuring characters, both native and non-native, who inhabit the city without ever feeling fully at home. As one remarks, “Rome switches between heaven and hell.” Like Whereabouts, Lahiri’s previous book, this collection was composed in Italian and then translated into English. Lahiri self-translated six out of the nine stories, entrusting editor Todd Portnowitz with the remaining three. The translation is supple and elegant throughout; sentences gleam and flow, adding to the vividness and immediacy of these tales about buried grief, belonging and unbelonging, the meaning of home and the cost of exile.

The characters, always unnamed, are sick and homesick; they worry about their bodies and they reminisce about past homes and past lives. Sometimes a parent, a friend or a child is remembered or mourned; always, a degree of guilt is involved. In The Procession, set during the festivities of La Festa de Noantri, a couple arrive in Rome to celebrate the wife’s 50th birthday. The city, we learn, holds a special place in her heart; it was where she had studied for a year when she was 19 and where she had fallen in love for the first time. But peace will repeatedly elude her during her stay. Upsetting details accumulate. Morning light that startles “like an electric charge”; a chandelier that threatens to come crashing down. French doors that slam and shatter. A room that will not unlock. Another that brings to mind an operating theatre and a dead son.

More here.

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer.

Bacteria may seem like a strange ally in the battle against cancer. “What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

“What’s that thing with the fire?” a woman from the table behind me asks, tugging on the vents of my tuxedo jacket and gesturing toward the dessert I just finished flambéing. I’m tempted to lie and tell her we just sold out, but instead I explain the Bananas Foster — caramelized bananas flamed with dark rum over house-made banana-buttermilk ice cream — the restaurant’s most popular dessert. But she isn’t listening. I can already sense her plans to cast me as the lead in her TikTok video or the poster child for her “en fuego” meme. “Oh my God, I hate bananas,” she says, turning toward her tablemates, “but we should totally order it anyway!” They haven’t even finished their appetizers.

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my

If you’re new to my work, I’m a self-taught researcher, driven to learn through fortunate access to high sample sizes and sheer curiosity. As of this writing, over 700,000 people have responded to my

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon.

‘That’s our mountain,’ a wordy Neapolitan told Hester Piozzi, ‘which throws up money for us, by calling foreigners to see the extraordinary effects of so surprising a phenomenon.’ The hermits were only one part of a flourishing and lucrative Vesuvius service industry that visitors encountered as they began their ascents. As Brewer says, what the industry was ‘selling was a sublime experience’. Making your own way up the mountain to see the extraordinary effects was perilous, but help was at hand. Your first encounter upon arrival would be with a disorganised horde of vociferous guides, all offering their services. The spectacle seems to have been distinctly off-putting: the poet Shelley, generally a friend of humanity, thought these particular humans ‘degraded, disgusting & odious’. Degraded or not, some guides became celebrities: Salvatore Madonna (‘il capo cicerone’) was well-known for his narrative skills and general charm, as well as for his knowledge of the territory, and he even appeared in guidebooks as a colourful feature of the scene to be looked out for. Madonna seems to have been a professional type, but untrustworthy guides were not uncommon. Aviation produces about

Aviation produces about Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “

Staring into the mirror, on a Tuesday morning, you decide that your self needs all the help it can get. But where to turn? You were reading James Clear’s “ Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the

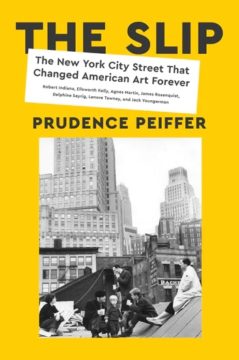

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the  BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist.

BETWEEN 1956 AND 1967, the Coenties Slip on the lower tip of Manhattan was home to a group of artists who had moved to the city with grand ambitions for their work and little money to their names. In those lean years, before they were canonized, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, Jack Youngerman, and Delphine Seyrig all took up residence in this “down downtown,” on a dead-end street on the East River where they nested themselves among fishing ships and sailors, the changing tides and unremitting grime, living at a remove from the New York City art world. Here on “the Slip”—a commercial dock designed for transience and exchange—they lived in cheap and drafty lofts, nurturing intuitions and ideas into radical practices, producing bodies of work that would, in the end, be very much a part of the zeitgeist. Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations.

Noisy. Hysterical. Brash. The textual version of junk food. The selfie of grammar. The exclamation point attracts enormous (and undue) amounts of flak for its unabashed claim to presence in the name of emotion which some unkind souls interpret as egotistical attention-seeking. We’ve grown suspicious of feelings, particularly the big ones needing the eruption of a ! to relieve ourselves. This trend started sometime around 1900 when modernity began to mean functionality and clean straight lines (witness the sensible boxes of a Bauhaus building), rather than the “extra” mood of Victorian sensitivity or frilly playful Renaissance decorations. David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of

David Deutsch is one of the most creative scientific thinkers working today, who has as a goal to understand and explain the natural world as best we can. He was a pioneer in quantum computing, and has long been an advocate of the Everett interpretation of quantum theory. He is also the inventor of  What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly.

What happens when lonely men, embittered by a sense of failure in the sexual marketplace, find each other and form communities on the internet? The result can be deadly.