Nina Power in Compact:

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of beauty, the passé concerns of previous centuries, the art world has become the moral directorate of the social order. Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square” became 2020’s Instagram BLM square—and woe betide anyone who failed to correctly perform the ritual. As Guy Debord put it in his 1988 “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” “since art is dead, it has evidently become extremely easy to disguise police as artists.”

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of beauty, the passé concerns of previous centuries, the art world has become the moral directorate of the social order. Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square” became 2020’s Instagram BLM square—and woe betide anyone who failed to correctly perform the ritual. As Guy Debord put it in his 1988 “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” “since art is dead, it has evidently become extremely easy to disguise police as artists.”

The growing tendency of artists to pronounce on everything from microaggressions to macropolitics shows that we need a fundamentally different understanding of the role played by artists and their institutions. The trend reached an apex last week, as a whole spate of open letters about Israel and Gaza were furiously signed and published. The frenzy culminated in the sacking on Thursday of David Velasco, editor in chief of Artforum, the prestigious contemporary-art monthly. Since then, several other Artforum editors—Chloe Wyma, Zack Hatfield, and Kate Sutton—have resigned. The hashtag #BoycottArtforum is circulating on social media, asking people to refuse to open or share links to Artforum content or to participate in any Artforum interviews or events. As the critic Adam Lehrer acerbically commented on X, “I haven’t opened an Artforum link in years, so I’ve been doing hella activism.”

More here.

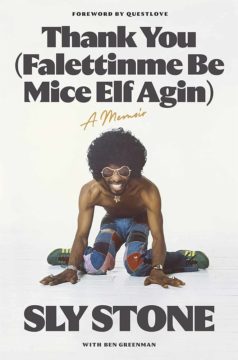

One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.”

One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.” Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like.

Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like. The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other.

The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other. Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle.

Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle. When I was in graduate school, I couldn’t make it through most of the talks presented in my department. I got bored and frustrated and tuned out. It was before smartphones, so I would doodle or fall asleep.

When I was in graduate school, I couldn’t make it through most of the talks presented in my department. I got bored and frustrated and tuned out. It was before smartphones, so I would doodle or fall asleep. Last week, we

Last week, we  This month marks an instructive centenary. On the morning of November 9, 1923, a 34-year-old Adolf Hitler led a column of 2,000 armed men through central Munich. The goal was to seize power by force in the Bavarian capital before marching on to Berlin. There, they would destroy the Weimar Republic – the democratic political system that had been established in Germany during the winter of 1918-19 – and replace it with an authoritarian regime committed to violence.

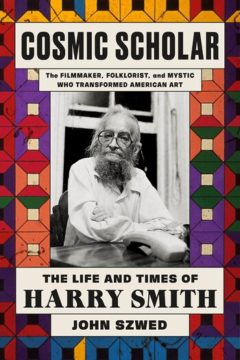

This month marks an instructive centenary. On the morning of November 9, 1923, a 34-year-old Adolf Hitler led a column of 2,000 armed men through central Munich. The goal was to seize power by force in the Bavarian capital before marching on to Berlin. There, they would destroy the Weimar Republic – the democratic political system that had been established in Germany during the winter of 1918-19 – and replace it with an authoritarian regime committed to violence. Smith was a loud ghost running wires between worlds, a “gnomish” saint who made connections more often than he made stuff. Hostile to the existence of galleries and museums and other obstacles to free circulation, Smith spent his life feeling for a pattern that might connect all the holy detritus in his ark: crushed Coke cans, paper airplanes, Seminole quilts, Ukrainian eggs, books, records, dead birds, string figures. The movies he painstakingly built from Vaseline and dye and paper cutouts changed how filmmakers saw the material of film itself. The problem for the historian is that Smith excelled in eliminating his own “excreta” (his word), throwing films under buses and tossing projectors out of windows. His close friend during the “Berkeley Renaissance” of 1948, the artist Jordan Belson, said that Smith “had nothing but insults and sarcasm for most art and most artists.” (This quote comes from the fantastic American Magus, a collection of interviews with those in Smith’s close circle first published in 1996, and one of Szwed’s sources.)

Smith was a loud ghost running wires between worlds, a “gnomish” saint who made connections more often than he made stuff. Hostile to the existence of galleries and museums and other obstacles to free circulation, Smith spent his life feeling for a pattern that might connect all the holy detritus in his ark: crushed Coke cans, paper airplanes, Seminole quilts, Ukrainian eggs, books, records, dead birds, string figures. The movies he painstakingly built from Vaseline and dye and paper cutouts changed how filmmakers saw the material of film itself. The problem for the historian is that Smith excelled in eliminating his own “excreta” (his word), throwing films under buses and tossing projectors out of windows. His close friend during the “Berkeley Renaissance” of 1948, the artist Jordan Belson, said that Smith “had nothing but insults and sarcasm for most art and most artists.” (This quote comes from the fantastic American Magus, a collection of interviews with those in Smith’s close circle first published in 1996, and one of Szwed’s sources.)