Category: Recommended Reading

How to monitor cell health in real-time

From Nature:

Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy — where a patient’s T cells are engineered to fight cancer — works well against blood cancers in young people, that success drops dramatically for older patients. The impact of ageing on an older patient’s T cells, so-called cell fitness, could be the problem.1 “By measuring key markers of cell health and metabolic state it should be possible to determine whether CAR-T cells are developing correctly,” says James Cali, director of research for the assay design department at Promega, a biotechnology company in Madison, Wisconsin. “By providing assays for those markers, we hope to help scientists understand the fitness of CAR-T cells for their intended therapeutic purpose.”

Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy — where a patient’s T cells are engineered to fight cancer — works well against blood cancers in young people, that success drops dramatically for older patients. The impact of ageing on an older patient’s T cells, so-called cell fitness, could be the problem.1 “By measuring key markers of cell health and metabolic state it should be possible to determine whether CAR-T cells are developing correctly,” says James Cali, director of research for the assay design department at Promega, a biotechnology company in Madison, Wisconsin. “By providing assays for those markers, we hope to help scientists understand the fitness of CAR-T cells for their intended therapeutic purpose.”

For CAR-T cells and other applications, scientists would like to track the health of cells in real time. Most cell health assays are endpoint assays, often including a reagent that kills the cells. As a result, these assays provide just one reading, and tracking the time course of changes in cell health requires multiple experiments — say, one at 30 minutes after a treatment, another at 60 minutes, and so on. With a kinetic assay, cells stay alive, and scientists can continuously monitor their health over a single experiment, saving time and resources.

More here.

Max Tegmark on superhuman AI, future architectures, and the meaning of human existence

Wednesday Poem

Clarinet

She’s a voice, they say

but when did you hear a human voice

sing such grace

in baroque quintets and ragtime bands alike?

lilt through the ornaments

and lament with so much reason?

glow

like a low star

then slide on up and scatter notes

far and wide, a firework

under the blackwood skies of the Jazz Age?

This is the world as sung to you by a long-

serving, sensible

weary angel

compassionate after all she’s seen but

not deceived.

Her saddest song

has a whisper deep inside

of translunary laughter:

the sorrows of all the people of all the world

shadow the phrases

she makes dance.

And with such sweet tears

– you realize

when it’s too late – she sings

that same old song again

for you, distingué lovers

so newly met in the garden

by Judith Taylor

from The Open Mouse

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

‘Without death, there is no art’: How Amitava Kumar’s new novel came to be

Amitava Kumar at Scroll.in:

For the first half of my life, certainly, when I was in my twenties, I was a great disappointment to my parents. College had held no interest for me. I was threatened that I had such a bad record of attendance at Hindu College that I would not be allowed to sit for my final-year exams. Each morning I boarded the University Special, the shuttle bus that the DTC provided for students, but I did so with the sole aim of sitting close to a girl I liked. (In three years, the sum total of our conversation had gone like this: “Would you like to read my poems?” “No.”) Then, I fell in love with another woman, from a different year, a year junior to me. I wrote her many letters, and even received responses, but we spent very little time together. We never even held hands. But I was happy. Instead of going to class, I sat on the college lawns smoking cigarettes, or reading in various libraries in the city, discovering poetry and fiction.

For the first half of my life, certainly, when I was in my twenties, I was a great disappointment to my parents. College had held no interest for me. I was threatened that I had such a bad record of attendance at Hindu College that I would not be allowed to sit for my final-year exams. Each morning I boarded the University Special, the shuttle bus that the DTC provided for students, but I did so with the sole aim of sitting close to a girl I liked. (In three years, the sum total of our conversation had gone like this: “Would you like to read my poems?” “No.”) Then, I fell in love with another woman, from a different year, a year junior to me. I wrote her many letters, and even received responses, but we spent very little time together. We never even held hands. But I was happy. Instead of going to class, I sat on the college lawns smoking cigarettes, or reading in various libraries in the city, discovering poetry and fiction.

I believed I was improving my mind.

More here.

Self-driving cars are underhyped

Matthew Yglesias in Slow Boring:

The Obama administration saw a flurry of tech sector hype about self-driving cars. Not being a technical person, I had no ability to assess the hype on the merits, but companies were putting real money into it, and so I wrote pieces looking at the labor market, land use, and transportation policy implications. But the tech turned out to be way overhyped, progress was much slower than advertised, and then Elon Musk further poisoned the water by marketing some limited (albeit impressive) self-driving software as “Full Self-Driving.”

The Obama administration saw a flurry of tech sector hype about self-driving cars. Not being a technical person, I had no ability to assess the hype on the merits, but companies were putting real money into it, and so I wrote pieces looking at the labor market, land use, and transportation policy implications. But the tech turned out to be way overhyped, progress was much slower than advertised, and then Elon Musk further poisoned the water by marketing some limited (albeit impressive) self-driving software as “Full Self-Driving.”

That whole experience seems to have left most people with the sense that self-driving cars are 10 years away and always will be.

I am still not a technical person, but at this point I am prepared to make a technical judgment: The current conventional wisdom is wrong and autonomous vehicle technology has become underhyped.

More here.

Ken Burns: Address to Brandeis University’s 2024 Graduates

How justified are recent claims that China has been buying significant quantities of debt to undermine the sovereignty of African nations?

Jamie Linsley-Parrish at JSTOR Daily:

In 2017, strategic studies scholar Brahma Chellaney accused China of using “debt-trap diplomacy” in its lending activities with African countries: in other words, buying significant quantities of debt to increase political leverage in the region. The accusation was leapt upon in the United States, with then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson claiming Chinese complicity in “miring nations in debt and undercutting their sovereignty.” Sixteen US senators and Tillerson’s successor, Mike Pompeo, subsequently used the term to decry Chinese “corruption” through such lending. But are such claims justified, or are they borne from anxiety around China’s rise to become a superpower and the subsequent implications for the West?

In 2017, strategic studies scholar Brahma Chellaney accused China of using “debt-trap diplomacy” in its lending activities with African countries: in other words, buying significant quantities of debt to increase political leverage in the region. The accusation was leapt upon in the United States, with then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson claiming Chinese complicity in “miring nations in debt and undercutting their sovereignty.” Sixteen US senators and Tillerson’s successor, Mike Pompeo, subsequently used the term to decry Chinese “corruption” through such lending. But are such claims justified, or are they borne from anxiety around China’s rise to become a superpower and the subsequent implications for the West?

More here.

What Is Stoicism?

Ketamine

Dan Piepenbring at The Baffler:

There’s the crux of the issue: the k-hole. Ketamine gets you really, elaborately, bizarrely high. Doctors have never quite known how to describe this high or what to do about it. During the drug’s clinical trials in 1964, recovering patients reported that they’d been dead, suspended among the stars, or living in a movie. One researcher observed that ketamine “produced ‘zombies’ who were totally disconnected from their environment.” Investigators had to find the right word to broach these effects; hallucinations and zombies wouldn’t go over well with the FDA. An early contender, schizophrenomimetic (i.e., mimicking schizophrenia), was tossed out for obvious reasons. They settled on dissociative, which suggested a gossamer untethering of body and brain. A hot air balloon dissociates from the earth; the two halves of a Venn diagram are a dissociated circle. Confusingly, there was already a long history of dissociation in psychology, where the word describes someone too detached from reality to function. Dissociative anesthesia is technically unrelated, but people understandably conflate the two, especially now that ketamine is used in mental health contexts. Hence ketamine clinics speak of “the healing powers of dissociation”—seemingly the very thing of which you’d want to be healed.

There’s the crux of the issue: the k-hole. Ketamine gets you really, elaborately, bizarrely high. Doctors have never quite known how to describe this high or what to do about it. During the drug’s clinical trials in 1964, recovering patients reported that they’d been dead, suspended among the stars, or living in a movie. One researcher observed that ketamine “produced ‘zombies’ who were totally disconnected from their environment.” Investigators had to find the right word to broach these effects; hallucinations and zombies wouldn’t go over well with the FDA. An early contender, schizophrenomimetic (i.e., mimicking schizophrenia), was tossed out for obvious reasons. They settled on dissociative, which suggested a gossamer untethering of body and brain. A hot air balloon dissociates from the earth; the two halves of a Venn diagram are a dissociated circle. Confusingly, there was already a long history of dissociation in psychology, where the word describes someone too detached from reality to function. Dissociative anesthesia is technically unrelated, but people understandably conflate the two, especially now that ketamine is used in mental health contexts. Hence ketamine clinics speak of “the healing powers of dissociation”—seemingly the very thing of which you’d want to be healed.

more here.

Remembering Alice Munro

Sterling HolyWhiteMountain and others at The Paris Review:

I reread “Family Furnishings” this morning because it is one of my favorite stories and because I will be discussing it soon with my students and because Alice Munro, possibly the greatest short-story writer there ever was and certainly the greatest in the English language, is dead. One of my teachers at the University of Montana introduced me to the story when I was an undergrad who had just begun to write and was utterly lost and did not know yet that these two things were one and the same. The story was so far beyond me I had almost no sense of what was going on except that by the end the narrator had been exposed to her own ignorance and arrogance and emotional irresponsibility in a way that was permanently imprinted on me, most likely because I understood it as a premonition of what was to come in my own life. But it is also a story about how the narrator becomes a fiction writer, about the ways a person from a small town might become such a thing, the ways high art will come into your life and separate you from the people who don’t live for art—this is most of them—and the things you must give up in order to commit yourself to the discipline of writing, the ways you will almost certainly piss people off back home when you finally find a way to fork the lightning of the sentence. Munro is one of the only writers whose work has haunted me not just on the first read but more and more as I’ve gotten older. A good story will hold your attention for a while, but a great story will open a new door in your head and then will change with you as you go and “Furnishings” is that kind of story. Each time I read it I see a thing I somehow did not before and understand something about life I did not before or had purposely forgotten; Munro’s best work is always a step past me and no matter what I do or how much older I get it remains that way and I hope it stays that way.

I reread “Family Furnishings” this morning because it is one of my favorite stories and because I will be discussing it soon with my students and because Alice Munro, possibly the greatest short-story writer there ever was and certainly the greatest in the English language, is dead. One of my teachers at the University of Montana introduced me to the story when I was an undergrad who had just begun to write and was utterly lost and did not know yet that these two things were one and the same. The story was so far beyond me I had almost no sense of what was going on except that by the end the narrator had been exposed to her own ignorance and arrogance and emotional irresponsibility in a way that was permanently imprinted on me, most likely because I understood it as a premonition of what was to come in my own life. But it is also a story about how the narrator becomes a fiction writer, about the ways a person from a small town might become such a thing, the ways high art will come into your life and separate you from the people who don’t live for art—this is most of them—and the things you must give up in order to commit yourself to the discipline of writing, the ways you will almost certainly piss people off back home when you finally find a way to fork the lightning of the sentence. Munro is one of the only writers whose work has haunted me not just on the first read but more and more as I’ve gotten older. A good story will hold your attention for a while, but a great story will open a new door in your head and then will change with you as you go and “Furnishings” is that kind of story. Each time I read it I see a thing I somehow did not before and understand something about life I did not before or had purposely forgotten; Munro’s best work is always a step past me and no matter what I do or how much older I get it remains that way and I hope it stays that way.

more here.

A portrait of the artist as a young woman

Note: A tribute by Dr. Azra Raza to her beloved friend Mansoora Hasan

Tuesday Poem

Three Poems by Nils Peterson

By the Sea

To watch a seagull fly overhead,

a girl child on the beach in red pajamas

tilts her head back and back,

impossibly back to anyone a second older.

Now she digs a hole

tossing the sand back between her legs

as if her hands were forepaws.

Now she sits on her haunches

in the hole and draws a circle

all about herself.

Now she is safe from everything.

With William

With Black William, half Lab and half

Golden Retriever, at the percolation ponds.

He is learning he likes the water and stands in it

up to his chest, snaps three times at the midges, then

erupts up the bank in a great larruping horsey gallop

surrounded for a moment by a fine thin silvery shield

of water curved like the battle shields of the Assyrians.

Tao from a Train Window

……….. a white cow

……….. picks up her

……….. right foot and

……….. places it

……….. down again.

from: All the Marvelous Stuff

Caesura Editions, Poetry Center of San José, 2019

Ozempic keeps wowing: trial data show benefits for kidney disease

Rachel Fairbank in Nature:

The blockbuster diabetes drug Ozempic — also sold as the obesity drug Wegovy — can add another health condition to the list of maladies it alleviates. Researchers presented clinical-trial data today at a conference in Stockholm, showing that it significantly reduces the risk of kidney failure and death for people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Scientists are thrilled with the result, and think that the drug, otherwise known by its generic name, semaglutide, will eventually be proved to help a more general population of people with kidney disease. This trial is a first step towards that goal, they say.

The blockbuster diabetes drug Ozempic — also sold as the obesity drug Wegovy — can add another health condition to the list of maladies it alleviates. Researchers presented clinical-trial data today at a conference in Stockholm, showing that it significantly reduces the risk of kidney failure and death for people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Scientists are thrilled with the result, and think that the drug, otherwise known by its generic name, semaglutide, will eventually be proved to help a more general population of people with kidney disease. This trial is a first step towards that goal, they say.

Semaglutide manufacturer Novo Nordisk, based in Bagsværd, Denmark, announced in October that it had halted its kidney-disease trial because of a recommendation from an independent data-safety monitoring board that the overwhelmingly positive results made it unethical to continue to give some participants a placebo. But until now, it hadn’t revealed the full data analysis, which is also published today in The New England Journal of Medicine.

More here.

Sunday, May 26, 2024

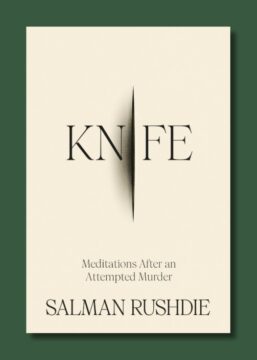

On Salman Rushdie’s ‘Knife’

Michael O’Donnell at The Millions:

Is Salman Rushdie an artist or a symbol? Can he be one but not the other? Or perhaps it’s an all-or-nothing affair and he is both or else neither. Ever since Rushdie, the author of 13 novels, was violently attacked onstage in August 2022 at a literary event, one line of thinking has it that his books should perforce be celebrated. The New Yorker embodied this view when it made the case, with very little discussion of Rushdie’s work, to award him the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was not an unpersuasive editorial, but in it, what Rushdie’s work represented outweighed what it contained. Yet if that’s the “both” case, the “neither” perspective feels even less satisfactory. Six days after the attempted murder, the American Conservative poured disdain on Rushdie as a free-speech icon and as a novelist, suggesting that anyone who mocks religion deserves a punch at the least and crassly asserting, “the fact that someone tried to kill an author doesn’t make that author’s books any good.”

Is Salman Rushdie an artist or a symbol? Can he be one but not the other? Or perhaps it’s an all-or-nothing affair and he is both or else neither. Ever since Rushdie, the author of 13 novels, was violently attacked onstage in August 2022 at a literary event, one line of thinking has it that his books should perforce be celebrated. The New Yorker embodied this view when it made the case, with very little discussion of Rushdie’s work, to award him the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was not an unpersuasive editorial, but in it, what Rushdie’s work represented outweighed what it contained. Yet if that’s the “both” case, the “neither” perspective feels even less satisfactory. Six days after the attempted murder, the American Conservative poured disdain on Rushdie as a free-speech icon and as a novelist, suggesting that anyone who mocks religion deserves a punch at the least and crassly asserting, “the fact that someone tried to kill an author doesn’t make that author’s books any good.”

More here.

What mosquitoes are most attracted to in human body odor is revealed

Kate Golembiewski at CNN:

“We were really motivated to try and develop a system where we could study the behavior of the African malaria mosquito in a naturalistic habitat, reflective of its native home in Africa,” McMeniman said. The researchers also wanted to compare the mosquitoes’ smell preferences across different humans, to observe the insects’ ability to track scents across distances of 66 feet (20 meters), and to study them during their most active hours, between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m.

“We were really motivated to try and develop a system where we could study the behavior of the African malaria mosquito in a naturalistic habitat, reflective of its native home in Africa,” McMeniman said. The researchers also wanted to compare the mosquitoes’ smell preferences across different humans, to observe the insects’ ability to track scents across distances of 66 feet (20 meters), and to study them during their most active hours, between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m.

To tick all these boxes, the researchers created a screened facility the size of a skating rink. Dotting the perimeter of the facility were six screened tents where study participants would sleep. Air from their tents, carrying the participants’ unique breath and body odor scents, was pumped through long tubes to the main facility onto absorbent pads, warmed and baited with carbon dioxide to mimic a sleeping human.

More here.

Ken Roth: Why is the west defending Israel after the ICC requested Netanyahu’s arrest warrant?

Ken Roth in The Guardian:

In a terse statement, Joe Biden called the charges “outrageous”, stating that “there is no equivalence – none – between Israel and Hamas”. The German government, while saying it “respects the independence” of the court, echoed this “false equivalence” charge. But Khan made no claim of equivalence. He simply charged both Israeli and Hamas officials for their own separate war crimes. Indeed, given the severity of the offenses, it would have been outrageous had Khan ignored one side’s crimes. The dual charges underscore a fundamental principle of international humanitarian law: war crimes by one side never justify war crimes by another.

In a terse statement, Joe Biden called the charges “outrageous”, stating that “there is no equivalence – none – between Israel and Hamas”. The German government, while saying it “respects the independence” of the court, echoed this “false equivalence” charge. But Khan made no claim of equivalence. He simply charged both Israeli and Hamas officials for their own separate war crimes. Indeed, given the severity of the offenses, it would have been outrageous had Khan ignored one side’s crimes. The dual charges underscore a fundamental principle of international humanitarian law: war crimes by one side never justify war crimes by another.

Ironically, Hamas responded to the proposed charges with a variation of this theme, saying that Khan’s action “equates the victim with the executioner”. But regardless of the perceived justness of one’s cause, it never justifies war crimes.

More here.

AI chatbots are intruding into online communities where people are trying to connect with other humans

Casey Fiesler in The Conversation:

A parent asked a question in a private Facebook group in April 2024: Does anyone with a child who is both gifted and disabled have any experience with New York City public schools? The parent received a seemingly helpful answer that laid out some characteristics of a specific school, beginning with the context that “I have a child who is also 2e,” meaning twice exceptional.

A parent asked a question in a private Facebook group in April 2024: Does anyone with a child who is both gifted and disabled have any experience with New York City public schools? The parent received a seemingly helpful answer that laid out some characteristics of a specific school, beginning with the context that “I have a child who is also 2e,” meaning twice exceptional.

On a Facebook group for swapping unwanted items near Boston, a user looking for specific items received an offer of a “gently used” Canon camera and an “almost-new portable air conditioning unit that I never ended up using.”

Both of these responses were lies. That child does not exist and neither do the camera or air conditioner. The answers came from an artificial intelligence chatbot.

More here.