Heidi Ledford in Nature:

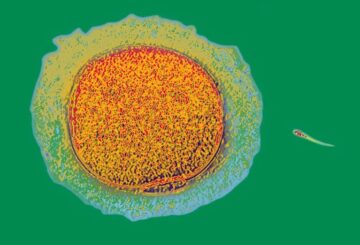

The day when human sperm and eggs can be grown in the laboratory has inched a step closer, with the discovery of a way to recreate a crucial developmental step in a dish1. The advance, described 20 May in Nature, addresses a major hurdle: how to ensure that the chemical tags on the DNA and associated proteins in artificially produced sperm and eggs are placed properly. These tags are part of a cell’s ‘epigenome’ and can influence whether genes are turned on or off. The epigenome changes over a person’s lifetime; during the development of the cells that will eventually give rise to sperm or eggs, these marks must be wiped clean and then reset to their original state.

The day when human sperm and eggs can be grown in the laboratory has inched a step closer, with the discovery of a way to recreate a crucial developmental step in a dish1. The advance, described 20 May in Nature, addresses a major hurdle: how to ensure that the chemical tags on the DNA and associated proteins in artificially produced sperm and eggs are placed properly. These tags are part of a cell’s ‘epigenome’ and can influence whether genes are turned on or off. The epigenome changes over a person’s lifetime; during the development of the cells that will eventually give rise to sperm or eggs, these marks must be wiped clean and then reset to their original state.

“Epigenetic reprogramming is key to making the next generation,” says Mitinori Saitou, a stem-cell biologist at Kyoto University in Japan, and a co-author of the paper. He and his team worked out how to activate this reprogramming — something that had been one of the biggest challenges in generating human sperm and eggs in the laboratory, he says. But Saitou is quick to note that there are further steps left to conquer, and that the epigenetic reprogramming his lab has achieved is not perfect. “There is still much work to be done and considerable time required to address these challenges,” agrees Fan Guo, a reproductive epigeneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Zoology in Beijing.

More here.

‘C

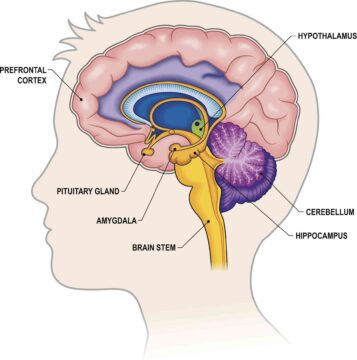

‘C I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions that

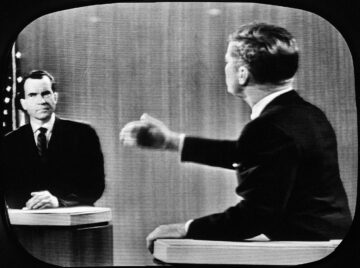

I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions that  Donald Trump is incapable of meaningful participation in such an event. Only in the sense that “match” can apply to both chess and mud wrestling could the word “debate” apply both to the Kennedy-Nixon event and to Trump’s on-stage behavior. Trump cannot help but distort a debate into a cage-fight. He will, again, shamelessly lie and endlessly interrupt.

Donald Trump is incapable of meaningful participation in such an event. Only in the sense that “match” can apply to both chess and mud wrestling could the word “debate” apply both to the Kennedy-Nixon event and to Trump’s on-stage behavior. Trump cannot help but distort a debate into a cage-fight. He will, again, shamelessly lie and endlessly interrupt. Earlier this year, the singer and songwriter Billie Eilish, who is twenty-two, became the youngest two-time Oscar winner in history, collecting the Best Original Song award for “What Was I Made For?,” a delicate existential ballad that she co-wrote for the film “

Earlier this year, the singer and songwriter Billie Eilish, who is twenty-two, became the youngest two-time Oscar winner in history, collecting the Best Original Song award for “What Was I Made For?,” a delicate existential ballad that she co-wrote for the film “ On the edge of the Alameda, practically bumping up against the old Church of Saint Francis, the gay club flashes a fuchsia neon sign that sparks the sinful festivities. An invitation to go down the steps and enter the colorful furnace of music-fever sweating on the dance floor. The fairy parade descends the uneven staircase like goddesses of a Mapuche Olympus. High and mighty, their stride gliding right over the threadbare carpet. Magnificent and exacting as they adjust the safety pins in their freshly ironed pants. Practically queens, if not for the loose red stitches of a quickie fix. Practically stars, except for the fake jeans logo tattooed on one of the asscheeks.

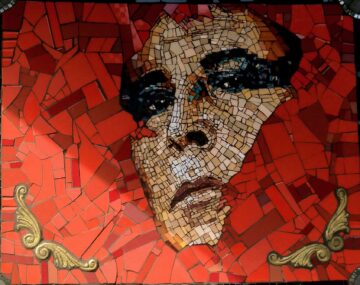

On the edge of the Alameda, practically bumping up against the old Church of Saint Francis, the gay club flashes a fuchsia neon sign that sparks the sinful festivities. An invitation to go down the steps and enter the colorful furnace of music-fever sweating on the dance floor. The fairy parade descends the uneven staircase like goddesses of a Mapuche Olympus. High and mighty, their stride gliding right over the threadbare carpet. Magnificent and exacting as they adjust the safety pins in their freshly ironed pants. Practically queens, if not for the loose red stitches of a quickie fix. Practically stars, except for the fake jeans logo tattooed on one of the asscheeks. Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the  H

H The

The  Getting microbes to eat plastic is a frequently touted solution to our growing waste problem, but making the approach practical is tricky. A new technique that impregnates plastic with the spores of plastic-eating bacteria could make the idea a reality. The impact of plastic waste on the environment and our health has gained increasing attention in recent years. The latest round of UN talks aiming for a global treaty to end plastic pollution

Getting microbes to eat plastic is a frequently touted solution to our growing waste problem, but making the approach practical is tricky. A new technique that impregnates plastic with the spores of plastic-eating bacteria could make the idea a reality. The impact of plastic waste on the environment and our health has gained increasing attention in recent years. The latest round of UN talks aiming for a global treaty to end plastic pollution  Whether mobilizing for war or (re)constructing advanced manufacturing capabilities in peacetime, success turns on the functioning of complex supply chains. But this truth was long forgotten – or at least under-appreciated. Not until recent supply-chain shocks did academics, policymakers, and others start paying more attention to the complicated, barely studied “meso” (middle) domain between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Whether mobilizing for war or (re)constructing advanced manufacturing capabilities in peacetime, success turns on the functioning of complex supply chains. But this truth was long forgotten – or at least under-appreciated. Not until recent supply-chain shocks did academics, policymakers, and others start paying more attention to the complicated, barely studied “meso” (middle) domain between microeconomics and macroeconomics. For thousands of years, humankind has fancied itself the apex of creation and the dominant force in the world. Yet humans are now gripped by the fear that yet another species of our own creation—artificially intelligent machines—will presently displace us from our position of unchallenged domination, perhaps even enslaving us.

For thousands of years, humankind has fancied itself the apex of creation and the dominant force in the world. Yet humans are now gripped by the fear that yet another species of our own creation—artificially intelligent machines—will presently displace us from our position of unchallenged domination, perhaps even enslaving us. I spent

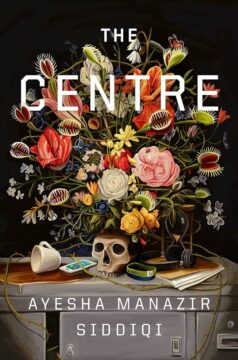

I spent  Language as self, language learning as magic, the mortifications of the flesh: these themes run through The Centre, a debut novel by British-Pakistani writer and translator Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi. Its narrator, Anisa, is a Pakistani translator of Urdu living in London, grappling with tensions of her immigrant identity and cosmopolitan desires. Yes, she had achieved her dream of moving to England but dislikes the cold and the myriad forms of casual racism she encounters. She complains that living outside of Pakistan has tainted her Urdu (her mother tongue) with Hindi words, and she resents the fact that she uses Urdu merely to translate Bollywood film subtitles — as opposed to the great literature she admires. To top it off, her other language, French, is mediocre. « Not like French-person French, » she complains to a friend.

Language as self, language learning as magic, the mortifications of the flesh: these themes run through The Centre, a debut novel by British-Pakistani writer and translator Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi. Its narrator, Anisa, is a Pakistani translator of Urdu living in London, grappling with tensions of her immigrant identity and cosmopolitan desires. Yes, she had achieved her dream of moving to England but dislikes the cold and the myriad forms of casual racism she encounters. She complains that living outside of Pakistan has tainted her Urdu (her mother tongue) with Hindi words, and she resents the fact that she uses Urdu merely to translate Bollywood film subtitles — as opposed to the great literature she admires. To top it off, her other language, French, is mediocre. « Not like French-person French, » she complains to a friend.