Rachel Brazil in Nature:

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”.

She clarifies that the editorial board of the journal, which launched in 2020, isn’t interested in papers in which “you did a shitty study and you found nothing. We’re interested in stuff that was done methodologically soundly, but still yielded a result that was unexpected.” These types of result — which do not prove a hypothesis or could yield unexplained outcomes — often simply go unpublished, explains Field, who is also an open-science researcher at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. Along with Stefan Gaillard, one of the journal’s founders, she hopes to change that.

Calls for researchers to publish failed studies are not new. The ‘file-drawer problem’ — the stacks of unpublished, negative results that most researchers accumulate — was first described in 1979 by psychologist Robert Rosenthal. He argued that this leads to publication bias in the scientific record: the gap of missing unsuccessful results leads to overemphasis on the positive results that do get published.

More here.

Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you?

Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you? In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and

In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and  Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history.

Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history. Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.

Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system.

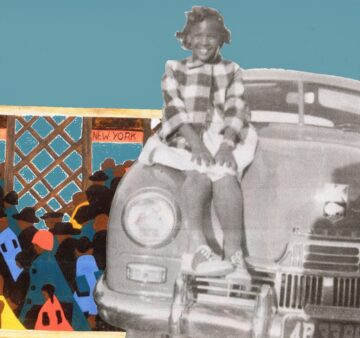

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by the late actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures aiming to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system. As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places.

As the historian Nell Irvin Painter has learned over the course of her eight decades on this earth, inspiration can come from some unlikely places. Since the 19th century, large numbers of villagers in the poorer parts of Italy have migrated to more prosperous regions and countries. The migration continues; in some places, populations have shrunk so dramatically that there are no longer enough patients to keep the local doctor in business, or enough children to fill the school. Young people who moved away to study or work didn’t want to return, and when their parents died, the family homes stood empty, sometimes for decades. Around 2010, the village of Salemi in western Sicily was one of the first towns to come up with an idea: What if you could fill them again by offering the properties for sale at a ridiculously low price?

Since the 19th century, large numbers of villagers in the poorer parts of Italy have migrated to more prosperous regions and countries. The migration continues; in some places, populations have shrunk so dramatically that there are no longer enough patients to keep the local doctor in business, or enough children to fill the school. Young people who moved away to study or work didn’t want to return, and when their parents died, the family homes stood empty, sometimes for decades. Around 2010, the village of Salemi in western Sicily was one of the first towns to come up with an idea: What if you could fill them again by offering the properties for sale at a ridiculously low price?