Jeremy Waldron in Political Philosophy:

What makes something a damned lie? It’s an odd question, but I want to use the phrase as a lens for examining the wrongness (and variations in the wrongness) of lying in a number of different areas of public life.

Towards the end of his (first) presidency, headlines in several op-ed pieces talked about the “damned lies” of President Trump. Paul Krugman had a column in the New York Times titled “Lies, Damned Lies and Trump Rallies.” John Nichols wrote that “The President’s Damned Lies Are Killing Us.” And way back in 2018, the National Catholic Reporter headlined an opinion piece “Lies, Damned Lies, and Presidential Tweets.”1 It’s a familiar phrase, and it sounded good. But what were they getting at? Is “damned lies” anything more than rhetoric? Our authors offered no insight into what they meant. The phrase “damned lies,” which appears only in titles but not in texts, is evidently just an expression—a way to denounce the former President’s lying.2 The phrase looks like it’s meant to pick out a particularly egregious kind of lie—qualitatively different from ordinary lies. But Krugman et al. didn’t tell us what a lie horrendous enough to be damned would consist in.

Donald Trump, we know, is a liar—not just in the sense that he has told lies (which most of us do sometimes), but in the sense of being an inveterate lie-teller, thousands upon thousands of lies, a man whose propensity to falsehood is one of the leading hallmarks of his character. Here too, terminology is interesting…

More here.

Dakwar explores the myths and misconceptions of addiction, as well as the science, and shows how the patient’s experience is at least as important as what the latest research tells us. He describes in detail the use of ketamine given in combination with psychotherapy, and of the difficulties he has faced acquiring permission and funding to pursue his research into a treatment that itself suffers from being labelled a dangerous “street” drug.

Dakwar explores the myths and misconceptions of addiction, as well as the science, and shows how the patient’s experience is at least as important as what the latest research tells us. He describes in detail the use of ketamine given in combination with psychotherapy, and of the difficulties he has faced acquiring permission and funding to pursue his research into a treatment that itself suffers from being labelled a dangerous “street” drug. L

L The region, we’re told, extends from the deserts of Sonora to the straits of Tierra del Fuego, encompassing 7.7 million square miles that are home to 660 million people who share two Latinate languages: Spanish and Portuguese. What complicates the picture is that many in that vast expanse also speak Nahuatl, Quechua, and hundreds of other tongues. But it’s not just the language: the people of this region, we hear, are

The region, we’re told, extends from the deserts of Sonora to the straits of Tierra del Fuego, encompassing 7.7 million square miles that are home to 660 million people who share two Latinate languages: Spanish and Portuguese. What complicates the picture is that many in that vast expanse also speak Nahuatl, Quechua, and hundreds of other tongues. But it’s not just the language: the people of this region, we hear, are  “Any Person Is the Only Self,” the poet and critic Elisa Gabbert’s third collection of nonfiction, opens with an essay that should be, but isn’t quite, a mission statement. She starts by describing the Denver Public Library’s shelf for recent returns, a miscellaneous display of disconnected works she habitually browsed in the years she lived in Colorado. In part, Gabbert (who is also the Book Review’s poetry columnist) was drawn to the shelf for its “negative hype,” its opposition to the churn of literary publicity. But mainly, she enjoyed playing the odds. “Randomness is interesting,” she writes; “randomness looks beautiful to me.” At the essay’s end, she declares, “I need randomness to be happy.”

“Any Person Is the Only Self,” the poet and critic Elisa Gabbert’s third collection of nonfiction, opens with an essay that should be, but isn’t quite, a mission statement. She starts by describing the Denver Public Library’s shelf for recent returns, a miscellaneous display of disconnected works she habitually browsed in the years she lived in Colorado. In part, Gabbert (who is also the Book Review’s poetry columnist) was drawn to the shelf for its “negative hype,” its opposition to the churn of literary publicity. But mainly, she enjoyed playing the odds. “Randomness is interesting,” she writes; “randomness looks beautiful to me.” At the essay’s end, she declares, “I need randomness to be happy.” We live in a weird time for autonomous vehicles. Ambitions come and go, but genuinely autonomous cars are further off than solid-state vehicle batteries. Part of the problem with developing autonomous cars is that teaching road cars to take risks is unacceptable.

We live in a weird time for autonomous vehicles. Ambitions come and go, but genuinely autonomous cars are further off than solid-state vehicle batteries. Part of the problem with developing autonomous cars is that teaching road cars to take risks is unacceptable.

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), led by India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), led by India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has  The specter of failure, of course, looms large over creative people, whose identities are particularly bound up with their work; the stock character of the tortured artist dates back to Plato. Culturally, we tend to romanticize grandiose failure—artists who toiled in bitter agony or isolation or with complete lack of recognition their whole lives, only to become demigods after death (van Gogh, Emily Dickinson). In an essay in Boston Review, the critic Tom Bissell considers how fragile the phenomenon of writerly success is, exploring how names that are iconic and enduring today, like Herman Melville and Walt Whitman, could easily have been long lost, had it not been for an assortment of arbitrary occurrences: “Remaindered copies bought from book peddlers. A man, sitting at his desk, an oxidized copy of a forgotten novel beside him, cobbling together an essay with no idea of what it would accomplish.… Essays published at the right time, in the right journals or books, noticed by the right people.” The reasons many famous writers of yore continue to have star status has little to do with fate, Bissell writes, but rather with “the stagecraft of chance.” He quotes Melville—notoriously unsuccessful in his lifetime, writing to a friend in 1849 upon the flop of his novel Mardi. “[It] may possibly—by some miracle, that is—flower like aloe, a hundred years hence—or not flower at all, which is more likely by far, for some aloes never flower.”

The specter of failure, of course, looms large over creative people, whose identities are particularly bound up with their work; the stock character of the tortured artist dates back to Plato. Culturally, we tend to romanticize grandiose failure—artists who toiled in bitter agony or isolation or with complete lack of recognition their whole lives, only to become demigods after death (van Gogh, Emily Dickinson). In an essay in Boston Review, the critic Tom Bissell considers how fragile the phenomenon of writerly success is, exploring how names that are iconic and enduring today, like Herman Melville and Walt Whitman, could easily have been long lost, had it not been for an assortment of arbitrary occurrences: “Remaindered copies bought from book peddlers. A man, sitting at his desk, an oxidized copy of a forgotten novel beside him, cobbling together an essay with no idea of what it would accomplish.… Essays published at the right time, in the right journals or books, noticed by the right people.” The reasons many famous writers of yore continue to have star status has little to do with fate, Bissell writes, but rather with “the stagecraft of chance.” He quotes Melville—notoriously unsuccessful in his lifetime, writing to a friend in 1849 upon the flop of his novel Mardi. “[It] may possibly—by some miracle, that is—flower like aloe, a hundred years hence—or not flower at all, which is more likely by far, for some aloes never flower.” For Billie Holiday, solitude was no bargain. “In my solitude,” she tells us in one of her signature songs, she sits in her room, filled with despair, gloom everywhere, eminently sad, certain she’ll soon go mad. Were she alive today, Ms. Holiday would be astonished to learn that solitude is no longer the dark and dreary state described by the lyricists Eddie DeLange and Irving Mills, but one, au contraire, that needs to be cultivated on the way to a rounder, fuller, in many ways more healthy mental life.

For Billie Holiday, solitude was no bargain. “In my solitude,” she tells us in one of her signature songs, she sits in her room, filled with despair, gloom everywhere, eminently sad, certain she’ll soon go mad. Were she alive today, Ms. Holiday would be astonished to learn that solitude is no longer the dark and dreary state described by the lyricists Eddie DeLange and Irving Mills, but one, au contraire, that needs to be cultivated on the way to a rounder, fuller, in many ways more healthy mental life. The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently

The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently  This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit.

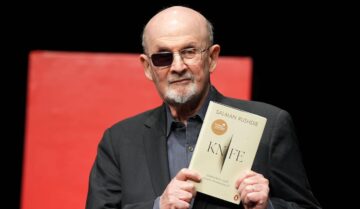

This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit. My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.

My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.