From City Journal:

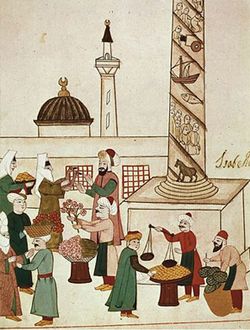

Muslim economies haven’t always been low achievers. In his seminal work The World Economy, economist Angus Maddison showed that until the twelfth century, per-capita income was much higher in the Muslim Middle East than in Europe. Beginning in the twelfth century, though, what Duke University economist Timur Kuran calls the Long Divergence began, upending this economic hierarchy, so that by Rifaa’s time, Europe had grown far more powerful and prosperous than the Arab Muslim world. A key factor in the divergence was Italian city-states’ invention of capitalism—a development that rested on certain cultural prerequisites, Stanford University’s Avner Greif observes. In the early twelfth century, two groups of merchants dominated Mediterranean sea trade: the European Genoans and the Cairo-based Maghrebis, who were Jewish but, coming originally from Baghdad, shared the cultural norms of the Arab Middle East. The Genoans outpaced the Maghrebis and eventually won the competition, Greif argues, because they invented various corporate institutions that formed the core of capitalism, including banks, bills of exchange, and joint-stock companies, which allowed them to accumulate enough capital to launch riskier but more profitable ventures. These institutions, in Greif’s account, were an outgrowth of the Genoans’ Western culture, in which people were bound not just by blood but also by contracts, including the fundamental contract of marriage. The Maghrebis’ Arab values, by contrast, meant undertaking nothing outside the family and tribe, which limited commercial expeditions’ resources and hence their reach. The bonds of blood couldn’t compete with fair, reliable institutions (see “Economics Does Not Lie,” Summer 2008).

Muslim economies haven’t always been low achievers. In his seminal work The World Economy, economist Angus Maddison showed that until the twelfth century, per-capita income was much higher in the Muslim Middle East than in Europe. Beginning in the twelfth century, though, what Duke University economist Timur Kuran calls the Long Divergence began, upending this economic hierarchy, so that by Rifaa’s time, Europe had grown far more powerful and prosperous than the Arab Muslim world. A key factor in the divergence was Italian city-states’ invention of capitalism—a development that rested on certain cultural prerequisites, Stanford University’s Avner Greif observes. In the early twelfth century, two groups of merchants dominated Mediterranean sea trade: the European Genoans and the Cairo-based Maghrebis, who were Jewish but, coming originally from Baghdad, shared the cultural norms of the Arab Middle East. The Genoans outpaced the Maghrebis and eventually won the competition, Greif argues, because they invented various corporate institutions that formed the core of capitalism, including banks, bills of exchange, and joint-stock companies, which allowed them to accumulate enough capital to launch riskier but more profitable ventures. These institutions, in Greif’s account, were an outgrowth of the Genoans’ Western culture, in which people were bound not just by blood but also by contracts, including the fundamental contract of marriage. The Maghrebis’ Arab values, by contrast, meant undertaking nothing outside the family and tribe, which limited commercial expeditions’ resources and hence their reach. The bonds of blood couldn’t compete with fair, reliable institutions (see “Economics Does Not Lie,” Summer 2008).

Greif’s theory suggests that cultural differences explain economic development better than religious beliefs do. Indeed, from a strictly religious perspective, one could view Muslims as having an advantage at creating wealth. After all, Islam is the only religion founded by a trader—one who also, by the way, married a wealthy merchant.The Koran has only good words for successful businessmen. Entrepreneurs must pay a 2.5 percent tax, the zakat, to the community to support the general welfare, but otherwise can make money guilt-free. Private property is sacred, according to the Koran. All this, needless to say, contrasts with the traditional Christian attitude toward wealth, which puts the poor on the fast track to heaven and looks down in particular on merchants (recall Jesus’s driving them from the Temple).

More here.