Nick Whitaker & J. Zachary Mazlish at Works in Progress:

Many entrepreneurs have tried to create prediction markets, contracts that trade on the outcome of future events. Luke Nosek, cofounder of PayPal, once worked on the problem. Sam Bankman-Fried, the jailed founder of cryptocurrency exchange FTX, is supposed to have originally wanted to build a prediction markets platform. A number of venture capital–backed start-ups are currently building prediction markets, including Kalshi, a prediction market regulated by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC); Manifold, a play money prediction market; and Polymarket, a crypto-based prediction market currently illegal in the US.

Many entrepreneurs have tried to create prediction markets, contracts that trade on the outcome of future events. Luke Nosek, cofounder of PayPal, once worked on the problem. Sam Bankman-Fried, the jailed founder of cryptocurrency exchange FTX, is supposed to have originally wanted to build a prediction markets platform. A number of venture capital–backed start-ups are currently building prediction markets, including Kalshi, a prediction market regulated by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC); Manifold, a play money prediction market; and Polymarket, a crypto-based prediction market currently illegal in the US.

Many academics have advocated for the creation of prediction markets. Economics Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow argued for their deregulation in Science, alongside Cass Sunstein, the most cited legal scholar; Thomas Schelling, one of the foremost game theorists; and Philip Tetlock, who created superforecasting. Economist Bryan Caplan’s Substack is called Bet On It, alluding to the value of wagering on beliefs: bets are costly for people with wrong beliefs and profitable for people with accurate ones. This is the promise of prediction markets: they could use the wisdom of crowds and the price mechanism of markets to land on highly accurate probabilities.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

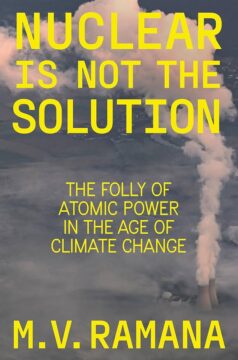

As someone trained in physics, and as an academic paid to research, I have been drawn to studying one essential contributor to these crises: how energy and electricity are produced, especially those methods proposed to mitigate climate change. Prominent among these proposals is nuclear energy.

As someone trained in physics, and as an academic paid to research, I have been drawn to studying one essential contributor to these crises: how energy and electricity are produced, especially those methods proposed to mitigate climate change. Prominent among these proposals is nuclear energy. Running a finger over a row of books in a Delhi library one afternoon, I stopped at a title that promised danger. The stacks were abundant in books like RSS Misunderstood and Is RSS the Enemy?, which often turned out to be self-published polemics that were too long, however short they were. This one was different. On its front was the full title,

Running a finger over a row of books in a Delhi library one afternoon, I stopped at a title that promised danger. The stacks were abundant in books like RSS Misunderstood and Is RSS the Enemy?, which often turned out to be self-published polemics that were too long, however short they were. This one was different. On its front was the full title,  Hundreds of millions of people across the globe now earn their living less with their backs and more with their brains, relying on sharp reasoning and creative thinking. So how about seeing who’s best at that?

Hundreds of millions of people across the globe now earn their living less with their backs and more with their brains, relying on sharp reasoning and creative thinking. So how about seeing who’s best at that? W

W OPEN ANY BOOK BY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD and you will encounter the same woman. Articulate, adrift, callous, cosmically self-absorbed. She’s in the middle of her life, a retired actress or model, once striking and sought-after. Her misery has a predatory quality. Decisions made idly and capriciously she now clings to as essential facets of her “character.” She rebels continually against the restraints and privations she inflicts upon herself. She behaves as though she were onstage, thundering dramatic monologues of deceit and self-justification. What’s clearest is her anger: pure, whole, just beneath the surface, like a calcium deposit under the skin.

OPEN ANY BOOK BY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD and you will encounter the same woman. Articulate, adrift, callous, cosmically self-absorbed. She’s in the middle of her life, a retired actress or model, once striking and sought-after. Her misery has a predatory quality. Decisions made idly and capriciously she now clings to as essential facets of her “character.” She rebels continually against the restraints and privations she inflicts upon herself. She behaves as though she were onstage, thundering dramatic monologues of deceit and self-justification. What’s clearest is her anger: pure, whole, just beneath the surface, like a calcium deposit under the skin. At the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, Jim Thorpe easily won the decathlon in the first modern version of the event. The grueling, ten-part feat was not the only addition to the burgeoning modern games. Other events that debuted at the 1912 Olympics included architecture, sculpture, painting, music… and literature.

At the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, Jim Thorpe easily won the decathlon in the first modern version of the event. The grueling, ten-part feat was not the only addition to the burgeoning modern games. Other events that debuted at the 1912 Olympics included architecture, sculpture, painting, music… and literature. Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results.

Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results. Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –

Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –  My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way.

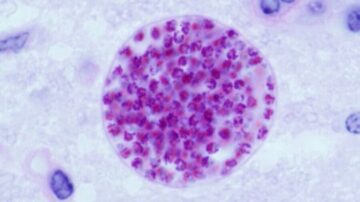

My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way. The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A

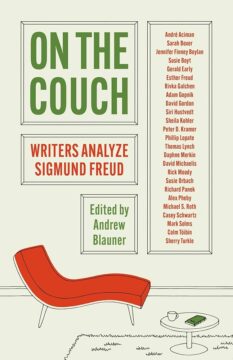

The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A  Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like

Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like