Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Light Devoured: From Surrogate Kings To Sun Shields

Mats Bigert at Cabinet Magazine:

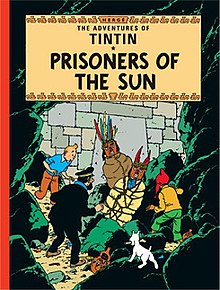

When Tintin is captured by an ancient Inca tribe in his fourteenth adventure, Prisoners of the Sun, he finds an article on his cell floor that forecasts a coming solar eclipse. This will prove to be significant since he, Captain Haddock, and Professor Calculus are to be burned at the stake. Tintin manages to see to it that the execution is staged at the right moment. When the Inca Prince of the Sun orders the pyre to be lit, Tintin invokes the Sun God: “O God of the Sun, sublime Pachacamac, display thy power, I implore thee! … If this sacrifice is not thy will, hide thy shining face from us!” In this patronizing Occidental fable of mathematical calculation triumphing over traditional belief, the weather god gives way to the scientist, whose knowledge gives Tintin the power to produce an apparent miracle.

When Tintin is captured by an ancient Inca tribe in his fourteenth adventure, Prisoners of the Sun, he finds an article on his cell floor that forecasts a coming solar eclipse. This will prove to be significant since he, Captain Haddock, and Professor Calculus are to be burned at the stake. Tintin manages to see to it that the execution is staged at the right moment. When the Inca Prince of the Sun orders the pyre to be lit, Tintin invokes the Sun God: “O God of the Sun, sublime Pachacamac, display thy power, I implore thee! … If this sacrifice is not thy will, hide thy shining face from us!” In this patronizing Occidental fable of mathematical calculation triumphing over traditional belief, the weather god gives way to the scientist, whose knowledge gives Tintin the power to produce an apparent miracle.

The scientist who made such exact prognostications possible was the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. In 1600, he was hired as an assistant by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and was given the painstaking task of analyzing observations of Mars made by Tycho and compiling them into a new set of astronomical tables.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

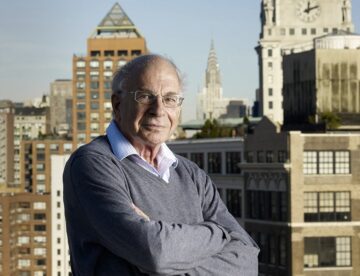

John Tooby (1952-2023)

From Edge:

JOHN TOOBY (July 26, 1952-November 9, 2023) was the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology, co-director (with his wife, Leda Cosmides) of the Center for Evolutionary Psychology, and professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara. He received his PhD in biological anthropology from Harvard University in 1989 and was professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Tooby and Cosmides also co-founded and co-directed the UCSB Center for Evolutionary Psychology and jointly received the 2020 Jean Nicod Prize.

JOHN TOOBY (July 26, 1952-November 9, 2023) was the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology, co-director (with his wife, Leda Cosmides) of the Center for Evolutionary Psychology, and professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara. He received his PhD in biological anthropology from Harvard University in 1989 and was professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Tooby and Cosmides also co-founded and co-directed the UCSB Center for Evolutionary Psychology and jointly received the 2020 Jean Nicod Prize.

Tooby was known for his work with his collaborators to integrate cognitive science, cultural anthropology, evolutionary biology, paleoanthropology, cognitive neuroscience, and hunter-gatherer studies to create the new field of evolutionary psychology, toward the goal of the progressive mapping of the universal evolved cognitive and neural architecture that constitutes human nature and provides the basis of the learning mechanisms responsible for culture. This involves using knowledge of specific adaptive problems our hunter-gatherer ancestors encountered to experimentally map the design of the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that evolved among our hominid ancestors to solve them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cancers with an Exceptional Cause

Kamal Nahas in The Scientist:

Cancers typically arise when cells accumulate mutations in their DNA that prevent them from keeping cell division in check.1 However, for some tumor types, researchers have struggled to find mutations, leading scientists to question their causes.2 Now, in a study published in Nature, researchers found that short-lived epigenetic changes can permanently alter gene expression and trigger cancer.3 While most cancers develop following mutations, their findings suggest that a few tumor types might deviate from this rule. For years, Giacomo Cavalli, a geneticist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and his colleagues have studied the role that epigenetic factors called Polycomb proteins play in cancer.4 These proteins form complexes that wind up chromatin and switch off genes that promote cell division. The team previously found that mutations in Polycomb factors cause chromatin unraveling, which cascades into cell proliferation and cancer initation.5 They wondered whether they could achieve the same effect by temporarily switching Polycomb genes off.

Cancers typically arise when cells accumulate mutations in their DNA that prevent them from keeping cell division in check.1 However, for some tumor types, researchers have struggled to find mutations, leading scientists to question their causes.2 Now, in a study published in Nature, researchers found that short-lived epigenetic changes can permanently alter gene expression and trigger cancer.3 While most cancers develop following mutations, their findings suggest that a few tumor types might deviate from this rule. For years, Giacomo Cavalli, a geneticist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and his colleagues have studied the role that epigenetic factors called Polycomb proteins play in cancer.4 These proteins form complexes that wind up chromatin and switch off genes that promote cell division. The team previously found that mutations in Polycomb factors cause chromatin unraveling, which cascades into cell proliferation and cancer initation.5 They wondered whether they could achieve the same effect by temporarily switching Polycomb genes off.

To test their hypothesis, they turned to the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster; the species has only one copy of each gene involved in the Polycomb machinery, making it easier to disrupt the system. Polycomb proteins play key roles during development by influencing the timing of cell differentiation. Cavalli and his team studied the impact of losing this epigenetic control on early, larval structures called imaginal discs. Using a temperature-sensitive RNA interference system, they exposed the discs to warmer temperatures for 24 hours, which temporarily turned off the Polycomb genes for two days. “They very nicely showed that with this transitory system they could switch off this development gene briefly, switch it back on, and that was enough to trigger tumorigenesis,” said Douglas Hanahan, a cancer biologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne who was not involved with the work.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

American Civil Wars

Richard Carwardine at Literary Review:

A mountain of historical studies testifies to enduring interest in the American Civil War, a conflict still politically relevant in a nation riven over how to remember it. Those doubting that there is anything fresh to say about the bloodiest event in the republic’s history should read Pulitzer Prize winner Alan Taylor’s brilliant, panoramic account of the conflict. Applying a wide continental lens, he explores this crux of United States history and how it shook neighbouring Mexico and Canada. In all three settings, liberals and social and political conservatives were involved in parallel struggles to build a modern nation. After a French invasion, the creation of a short-lived monarchy and a devastating civil war, the Liberal Party leader Benito Juárez returned to power in Mexico. Fearing the growing power and rapacity of the United States, meanwhile, Canadians navigated internal divisions to create a continental confederation. And in the United States, the pulsing heart and geographical centre of events, Abraham Lincoln’s Union forces subdued the reactionary and rebel slave power to achieve emancipation and the constitutional basis for a more liberal and democratic nation.

A mountain of historical studies testifies to enduring interest in the American Civil War, a conflict still politically relevant in a nation riven over how to remember it. Those doubting that there is anything fresh to say about the bloodiest event in the republic’s history should read Pulitzer Prize winner Alan Taylor’s brilliant, panoramic account of the conflict. Applying a wide continental lens, he explores this crux of United States history and how it shook neighbouring Mexico and Canada. In all three settings, liberals and social and political conservatives were involved in parallel struggles to build a modern nation. After a French invasion, the creation of a short-lived monarchy and a devastating civil war, the Liberal Party leader Benito Juárez returned to power in Mexico. Fearing the growing power and rapacity of the United States, meanwhile, Canadians navigated internal divisions to create a continental confederation. And in the United States, the pulsing heart and geographical centre of events, Abraham Lincoln’s Union forces subdued the reactionary and rebel slave power to achieve emancipation and the constitutional basis for a more liberal and democratic nation.

Taylor’s lively account of the conflict in the United States follows mostly familiar lines. Insisting that enslavement was a positive good for the people of African origin and that slavery had to grow to survive, Southerners demanded the right to settle the vast western territories beyond the Mississippi.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, July 29, 2024

Why I’ll never forget the day I met Daniel Kahneman for lunch

Namir Khaliq at Psyche:

The day I met Daniel Kahneman, he had asked me to join him for lunch at the Bowery Road restaurant in Lower Manhattan. Danny proposed this venue because it has comfortable booths and ‘is mostly deserted’. I arrived 15 minutes early, palms sweaty with the anticipation of meeting the world’s most famous psychologist. He had agreed to discuss making a film of his life’s work. I’d been preparing my pitch all week, and had brought a stack of notes with me to the restaurant. Half an hour passed, and he hadn’t arrived. I sent his secretary an email. Another 45 minutes ticked by before I abandoned hope. I headed back uptown, expectations shot.

The day I met Daniel Kahneman, he had asked me to join him for lunch at the Bowery Road restaurant in Lower Manhattan. Danny proposed this venue because it has comfortable booths and ‘is mostly deserted’. I arrived 15 minutes early, palms sweaty with the anticipation of meeting the world’s most famous psychologist. He had agreed to discuss making a film of his life’s work. I’d been preparing my pitch all week, and had brought a stack of notes with me to the restaurant. Half an hour passed, and he hadn’t arrived. I sent his secretary an email. Another 45 minutes ticked by before I abandoned hope. I headed back uptown, expectations shot.

As I walked through the apartment door, my phone buzzed. Danny’s name shone on the caller ID. ‘I’m terribly sorry,’ he said as soon as I answered. ‘Please tell me where to find you.’ I told him I could head back downtown in a few minutes. Before hanging up, he apologised once more: ‘I’m very sorry. This doesn’t usually happen. But I sometimes make mistakes.’

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

DeepMind AI gets silver medal at International Mathematical Olympiad

Alex Wilkins in New Scientist:

The IMO is considered the world’s most prestigious competition for young mathematicians. Correctly answering its test questions requires mathematical ability that AI systems typically lack.

The IMO is considered the world’s most prestigious competition for young mathematicians. Correctly answering its test questions requires mathematical ability that AI systems typically lack.

In January, Google DeepMind demonstrated AlphaGeometry, an AI system that could answer some IMO geometry questions as well as humans. However, this was not from a live competition, and it couldn’t answer questions from other mathematical disciplines, such as number theory, algebra and combinatorics, which is necessary to win an IMO medal.

Google DeepMind has now released a new AI, called AlphaProof, which can solve a wider range of mathematical problems, and an improved version of AlphaGeometry, which can solve more geometry questions.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sean Carroll on the Enigma of Complexity

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Francis Fukuyama: Who Is an American?

Francis Fukuyama at Persuasion:

In his acceptance speech for the vice presidency at the Republican National Convention, JD Vance stated that “one of the things that you hear people say sometimes is that America is an idea.” But, Vance asserted, the country was not just a “set of principles … but a homeland.” He went on to illustrate this by referring to his family’s cemetery where he hoped seven generations would be buried in a plot in eastern Kentucky. He said the country welcomed newcomers like his wife’s family from India, but “when we allow newcomers into our American family, we allow them on our terms.”

In his acceptance speech for the vice presidency at the Republican National Convention, JD Vance stated that “one of the things that you hear people say sometimes is that America is an idea.” But, Vance asserted, the country was not just a “set of principles … but a homeland.” He went on to illustrate this by referring to his family’s cemetery where he hoped seven generations would be buried in a plot in eastern Kentucky. He said the country welcomed newcomers like his wife’s family from India, but “when we allow newcomers into our American family, we allow them on our terms.”

Taken at face value, this should not be particularly controversial. American identity has always been based on ideas like liberty and equality, making it what is sometimes labeled a “creedal nation.” But it also is a nation of shared memory and experience. And it is doubtless true that immigrants to the United States need to accept certain basic conditions for being an American, as required by their taking the oath of naturalization during the citizenship ceremony.

The real question is what Vance means by the phrase “on our terms” as a condition for Americanness.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rowan Williams On Science And Religion

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Has Netanyahu finally lost America?

Joshua Keating in Vox:

In the past, Washington has served as a sort of relief valve for Netanyahu, a place he could count on strong support, even when his political position looked rocky at home. In that first speech back in 1996, after receiving a five-minute standing ovation from Congress, he quipped, “If I could only get the Knesset [Israel’s parliament] to vote like this.”

In the past, Washington has served as a sort of relief valve for Netanyahu, a place he could count on strong support, even when his political position looked rocky at home. In that first speech back in 1996, after receiving a five-minute standing ovation from Congress, he quipped, “If I could only get the Knesset [Israel’s parliament] to vote like this.”

Today, though, “the magic is gone,” Nimrod Novik, a former senior Israeli foreign policy official who is now an analyst at the Israel Policy Forum, told Vox. “The fellow that mastered verbal acrobatics to the point that different audiences could hear different messages in the same speech — that’s over. Those who were in awe of his verbal skills now take it with a grain of salt.”

In more than 40 years of coming to Washington, Netanyahu has surely grown used to being a controversial figure. He may have to get used to being an irrelevant one.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

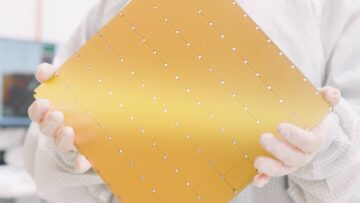

This Enormous Computer Chip Beat the World’s Top Supercomputer at Molecular Modeling

Jason Dorrier in Singularity Hub:

Computer chips are a hot commodity. Nvidia is now one of the most valuable companies in the world, and the Taiwanese manufacturer of Nvidia’s chips, TSMC, has been called a geopolitical force. It should come as no surprise, then, that a growing number of hardware startups and established companies are looking to take a jewel or two from the crown.

Computer chips are a hot commodity. Nvidia is now one of the most valuable companies in the world, and the Taiwanese manufacturer of Nvidia’s chips, TSMC, has been called a geopolitical force. It should come as no surprise, then, that a growing number of hardware startups and established companies are looking to take a jewel or two from the crown.

Of these, Cerebras is one of the weirdest. The company makes computer chips the size of tortillas bristling with just under a million processors, each linked to its own local memory. The processors are small but lightning quick as they don’t shuttle information to and from shared memory located far away. And the connections between processors—which in most supercomputers require linking separate chips across room-sized machines—are quick too.

This means the chips are stellar for specific tasks. Recent preprint studies in two of these—one simulating molecules and the other training and running large language models—show the wafer-scale advantage can be formidable. The chips outperformed Frontier, the world’s top supercomputer, in the former. They also showed a stripped down AI model could use a third of the usual energy without sacrificing performance.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

More Than A Half Century Of The Poetry Project

Sasha Frere-Jones at The Nation:

Like many creative ventures in cities that are in thrall to the real estate industry, the Poetry Project was itself a miracle, a space emerging out of the chaos and communal energy of a small circle. In 1966, a set of poets who had been gathering at Le Metro and Les Deux Mégots (pun and homage intentional) went through some internecine squabbles and found themselves in need of a new spot for readings. St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, on East 10th Street, was that place. Consecrated in 1799, it’s the second-oldest church building in Manhattan, located on New York’s oldest site of “continuous religious practice.” By the 1960s, it was home to something else, too: Theater Genesis had taken root there, jazz performances were happening during the summer, and poetry readings were common. The church’s reverend, Michael Allen, was active in protests against the war in Vietnam and was generally open to rogue events that might bring locals together.

As reported in Daniel Kane’s All Poets Welcome, the Poetry Project obtained its initial financial support in the form of an unlikely grant. A man named Israel Garver, a federal employee in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Development, was in charge of allocating funds that needed to be disbursed by the end of the fiscal year.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

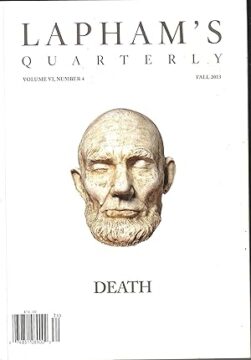

Lewis Lapham, The Art of Editing

Jim Holt chats with Lewis Lapham at the Paris Review:

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

By the time I arrived in New York in the late seventies, Lapham was established in the city’s editorial elite, up there with William Shawn at The New Yorker and Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers at The New York Review of Books. He was a glamorous fixture at literary parties and a regular at Elaine’s. In 1988, he raised plutocratic hackles by publishing Money and Class in America, a mordant indictment of our obsession with wealth. For a brief but glorious couple of years, he hosted a literary chat show on public TV called Bookmark, trading repartee with guests such as Joyce Carol Oates, Gore Vidal, Alison Lurie, and Edward Said.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, July 28, 2024

Biden’s Economic Legacy

Cameron Abadi and Adam Tooze over at Foreign Policy’s podcast Ones and Tooze:

Joe Biden still has six months left in his presidency, but it’s not too early to size up his economic legacy. Adam and Cameron dig in.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ready for War in Sweden

Gordon F. Sander in NY Review of Books:

While I was in Stockholm I met with Swedish defense minister Pål Jonson, who belongs to the Moderate Party, the largest member of the rickety center-right coalition—which also includes the Liberals and the Christian Democrats—that took office after the September 2022 elections. The week before, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the mercurial Turkish president, had dropped his long-standing objection to Sweden’s entry into NATO—in his view Stockholm had failed to take sufficiently aggressive action against alleged Kurdish “terrorists” living in Sweden. In March 2023, following an overwhelming vote by the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament, Stockholm had formally submitted its application to join the defensive alliance, on the same day as neighboring Finland, its closest ally. Then Erdoğan equivocated. And equivocated.

Sweden’s decision to finish shedding its two-century-old neutral status—something it had been doing gradually since the mid-1990s when it joined the EU as well as NATO’s associate program, the Partnership for Peace—required an even greater psychological leap than Finland’s. For Helsinki neutrality was never more than an expedient forced on it after its defeat by the Soviet Union during World War II. The bellicose Finns, who fought Soviet or Soviet-backed forces three times in the last century, were never neutral at heart. Swedes for the most part are—or at least were before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The last time Sweden engaged in a major war was in 1809, when it lost the Finnish War against Russia. Since then it had steadfastly adhered to its neutral status, including during World War II, which still rankles the conscience of many Swedes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sudan and the Silence of the Activists

Nesrine Malik in The Ideas Letter:

Some 20 years ago, the Darfur region of Sudan was in the throes of a brutal war against rebel African groups protesting their economic and political marginalization. Arab militias known as the Janjaweed joined the central government to quell the rebellion, and the repression soon metastasized into ethnic cleansing—and, some say, genocide. Outrage abroad over the atrocities spurred a global advocacy campaign that came to be known as the Save Darfur movement. Two decades later, Darfur is burning once again, but the network that once heeded its cries is now dramatically diminished.

At its peak, Save Darfur drew a constellation of celebrities from Hollywood, sports and politics, and from across lobbying and activist groups. Advocates included the actors George Clooney, Don Cheadle and Ryan Gosling, the Olympic speed-skating champion Joey Cheek, and a charismatic, young U.S. senator named Barack Obama. Addressing a crowd gathered at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in April 2006, Obama said of the conflict in Darfur: “If we care, the world will care. If we act, then the world will follow.”

The movement began in 2004 with the Save Darfur coalition, which sprang from established Jewish anti-genocide networks in the U.S. In July that year, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the American Jewish World Service organized the Darfur Emergency Summit in New York, featuring the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel, to draw attention to events in Darfur and make the case for intervention.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

We can breathe!

Gabriel Winant in The LRB:

In 1963, June Croll and Eugene Gordon took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Gordon was African American, raised in New Orleans; Croll was Jewish, born in Odessa at the beginning of the 20th century. Both fled their home cities as children to escape racial violence: Gordon, the Robert Charles riots of 1900, in which a mob of white Southerners murdered dozens after an African American man shot a police officer who had asked what he was doing in a mainly white neighbourhood; Croll, the Odessa pogrom of 1905, in which more than four hundred Jews were killed. Their story, uncovered by Daniel Candee, a former student of mine, forms an epic political anabasis. Croll became involved in communist politics and labour agitation in 1920s New York. Gordon, fresh from Howard University, became part of the New Negro movement and transformed the nationalist politics of Black self-defence, learned in his childhood, into communism in the early 1930s. Their relationship began at roughly the time the Popular Front was founded, and the movement offered them a way to universalise their early political commitment. They took part in workers’ struggles, but also fought for Black civil rights, women’s equality and decolonisation. As Richard Wright wrote, ‘there was no agency in the world so capable of making men feel the earth and the people upon it as the Communist Party.’

After Hitler came to power it soon became clear that the Comintern directive t0 national communist parties to adopt a sectarian ultra-leftist strategy wasn’t working, and that some form of co-operation with other parties was necessary to counter the fascist threat. In July 1935 the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern instructed national communist parties to form ‘popular fronts’ with anti-fascist forces, including factional rivals and liberal parties. Joseph Fronczak’s Everything Is Possible describes the consequences this decision had all over the world.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

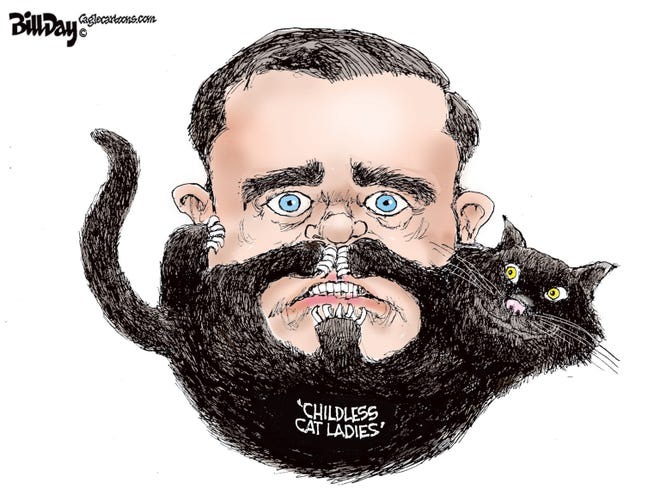

JD Vance finding out childless cat ladies bite and scratch

A simple, selfless dissent for integrity

From The Christian Science Monitor:

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

Thích Minh Tuệ’s story reflects a bubbling debate among corruption fighters around the world about whether to focus less on corruption itself and more on the intrinsic integrity and honesty of people. “There have been growing calls for a renewed focus on the central role of values, ethics and integrity in controlling corruption,” stated a 2022 report by the watchdog Transparency International.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.