Andrea Branchi at Aeon Magazine:

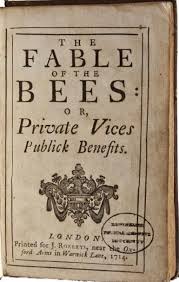

In 1714, and in an enlarged edition in 1723, Mandeville published the prose volume that made him infamous: The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits. The original poem was reprinted with a series of commentary essays in which Mandeville expanded upon his provocative arguments that human beings are self-interested, governed by their passions rather than their reason, and he offered an explanation of the origin of morality based solely on human sensitivity to praise and fear of shame through a rhapsody of social vignettes. Mandeville confronted his contemporaries with the disturbing fact that passions and habits commonly denounced as vices actually generate the welfare of a society.

In 1714, and in an enlarged edition in 1723, Mandeville published the prose volume that made him infamous: The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits. The original poem was reprinted with a series of commentary essays in which Mandeville expanded upon his provocative arguments that human beings are self-interested, governed by their passions rather than their reason, and he offered an explanation of the origin of morality based solely on human sensitivity to praise and fear of shame through a rhapsody of social vignettes. Mandeville confronted his contemporaries with the disturbing fact that passions and habits commonly denounced as vices actually generate the welfare of a society.

The idea that self-interested individuals, driven by their own desires, act independently to realise goods and institutions made The Fable of the Bees one of the chief literary sources of the laissez-faire doctrine. It is central to the economic concept of the market. In 1966, the free-market evangelist Friedrich von Hayek offered an enthusiastic reading of Mandeville that anointed the poet as an early theorist of the harmony of interests in a free market economy, a scheme that Hayek claimed was later expanded on by Adam Smith, reworking Mandeville’s paradox of ‘private vices, public benefits’ into the profoundly influential metaphor of the invisible hand. Today, Mandeville is standardly thought of as an economic thinker.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How many times during the past month have you gone to the dictionary, or if not the dictionary then to your computer, to look up a word? I go to mine with some frequency. Here are some of the words within recent weeks I’ve felt the need to look up: “algolagnia,” “orthoepist,” “cromulent,” “himation,” “cosplaying,” and “collocation.” The last word I half-sensed I knew but was less than certain about. I also looked up “despise” and “loath,” to be sure about the difference, if any, between them, and then had to check the difference between the latter when it has an “e” at its end and when it doesn’t. Over the years I must have looked up the word “fiduciary” at least half a dozen times, though I have never used it in print or conversation. I hope to look it up at least six more times before departing the planet. Working with words, it seems, is never done.

How many times during the past month have you gone to the dictionary, or if not the dictionary then to your computer, to look up a word? I go to mine with some frequency. Here are some of the words within recent weeks I’ve felt the need to look up: “algolagnia,” “orthoepist,” “cromulent,” “himation,” “cosplaying,” and “collocation.” The last word I half-sensed I knew but was less than certain about. I also looked up “despise” and “loath,” to be sure about the difference, if any, between them, and then had to check the difference between the latter when it has an “e” at its end and when it doesn’t. Over the years I must have looked up the word “fiduciary” at least half a dozen times, though I have never used it in print or conversation. I hope to look it up at least six more times before departing the planet. Working with words, it seems, is never done. Here’s a threshold AI may be approaching: it may soon be the first technology to be more adaptable than we are. It’s not there yet, but you can see it coming – the range of problems to which early adopters are successfully applying AI is simply exploding. Past inventions had limited impact, because they could only be adapted to some uses. But AI may (eventually) adapt itself to any task. When technology makes one job obsolete, people move into another – one that hasn’t been automated yet. But at some point, AI could be retraining faster than people can.

Here’s a threshold AI may be approaching: it may soon be the first technology to be more adaptable than we are. It’s not there yet, but you can see it coming – the range of problems to which early adopters are successfully applying AI is simply exploding. Past inventions had limited impact, because they could only be adapted to some uses. But AI may (eventually) adapt itself to any task. When technology makes one job obsolete, people move into another – one that hasn’t been automated yet. But at some point, AI could be retraining faster than people can. When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.” The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains. In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat? As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s.

As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s. ‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines.

‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines. Tom Wolfe was a fast talker.

Tom Wolfe was a fast talker.  Amitava Kumar has long occupied a distinctive place in contemporary English writing. His work resists easy classification, blurring the boundaries between fiction, memoir, reportage, history and critique.

Amitava Kumar has long occupied a distinctive place in contemporary English writing. His work resists easy classification, blurring the boundaries between fiction, memoir, reportage, history and critique. How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 2045. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.