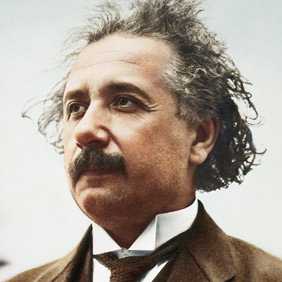

Since today is the 134th anniversary of the birth of Albert Einstein, as a tribute to my greatest hero I am posting an essay I wrote almost eight years ago over a weekend in Shrewsbury, Massachussettes, at my sister Azra's house in which I attempted to present a very short explanation of Einstein's remarkable theory of Special Relativity. Don't let the straighforward math scare you, if you work your way slowly through it, I hope that you will be rewarded by a feeling of satisfaction and understanding.

A century ago, this was the situation: Galilean and Newtonian physics said that any descriptions of motion by any two inertial observers (for such observers, bodies acted on by no forces move in straight lines) in uniform (not accelerating) relative motion are equally valid, and the laws of physics must be exactly the same for both of them. Bear with me here: what this means is, for example, if you see me coming toward you at a speed of 100 mph, then we could both be moving toward each other at 50 mph, or I could be still and you could be moving toward me at 100 mph, or I could be moving toward you at 30 mph while you are coming at me at 70 mph, and so on. All these descriptions are equivalent, and it is always impossible to tell whether one of us is “really” moving or not; all we can speak about is our motion relative to each other. In other words, all motion is relative to something else (which is then the inertial frame of reference). So for convenience, we can always just insist that any one observer is still (she is then the “frame of reference”) and all others are in motion relative to her. This is known as the Principle of Relativity. Another way to think about this is to imagine that there are only two objects in the universe, and they are moving relative to one another: in this situation it is more clearly impossible to say which object is moving. (Think about this paragraph, reread it, until you are pretty sure you get it. Just stay with me, it gets easier from here.)

A century ago, this was the situation: Galilean and Newtonian physics said that any descriptions of motion by any two inertial observers (for such observers, bodies acted on by no forces move in straight lines) in uniform (not accelerating) relative motion are equally valid, and the laws of physics must be exactly the same for both of them. Bear with me here: what this means is, for example, if you see me coming toward you at a speed of 100 mph, then we could both be moving toward each other at 50 mph, or I could be still and you could be moving toward me at 100 mph, or I could be moving toward you at 30 mph while you are coming at me at 70 mph, and so on. All these descriptions are equivalent, and it is always impossible to tell whether one of us is “really” moving or not; all we can speak about is our motion relative to each other. In other words, all motion is relative to something else (which is then the inertial frame of reference). So for convenience, we can always just insist that any one observer is still (she is then the “frame of reference”) and all others are in motion relative to her. This is known as the Principle of Relativity. Another way to think about this is to imagine that there are only two objects in the universe, and they are moving relative to one another: in this situation it is more clearly impossible to say which object is moving. (Think about this paragraph, reread it, until you are pretty sure you get it. Just stay with me, it gets easier from here.)

At the same time, James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electricity and magnetism implied that the speed of light in a vacuum, c, is absolute. The only way that this could be true is if Maxwell's equations refer to a special frame (see previous paragraph) of reference (that in which the speed of light is c) which can truly be said to be at rest. If this is the case, then an observer moving relative to that special frame would measure a different value for c. But in 1887, Michelson and Morley proved that there is no such special frame. Another way of saying this (and this is the way Einstein put it in 1905) is that the speed of light is fixed, and is independent of the speed of the body emitting it. (The details of the Michelson-Morley experiment are beyond the scope of this essay, so you'll have to take my word for this.)

Now we have a problem. We have two irreconcilable laws: 1) The Principle of Relativity, and 2) The absoluteness of the speed of light for all observers. They cannot both be true. It would be another eighteen years before a young clerk in the Swiss patent office would pose and then resolve this problem. Here's how he did it: he asked what would happen if they were both true.

Next, I will show how the various aspects of SR fall straight out of the assumption that both of these laws are true. I will focus in greater detail on the slowing down (dilation) of time, and then speak more briefly about length contraction, and the intertwining of space and time.

More here. Some months later I also wrote an short explanation of some aspects of General Relativity which you can read here.