Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The Great American Nuclear Weapons Upgrade

Ramin Skibba at Undark:

In the plains of western South Dakota, about 25 miles northeast of Mount Rushmore, the Ellsworth Air Force Base is preparing to receive the first fleet of B-21 nuclear bombers, replacing Cold War-era planes. Two other bases, Dyess in Texas and Whiteman in Missouri, will soon follow. By the 2030s, a total of five bases throughout the United States will host nuke-carrying bombers for the first time since the 1990s.

In the plains of western South Dakota, about 25 miles northeast of Mount Rushmore, the Ellsworth Air Force Base is preparing to receive the first fleet of B-21 nuclear bombers, replacing Cold War-era planes. Two other bases, Dyess in Texas and Whiteman in Missouri, will soon follow. By the 2030s, a total of five bases throughout the United States will host nuke-carrying bombers for the first time since the 1990s.

The planes are part of an estimated $1.7 trillion military program advancing the nuclear arsenal of the United States, as tensions continue to rise with nuclear-armed rivals Russia and China. In addition to the B-21s, the Pentagon is upgrading larger aging bombers and may also restore nukes to the ones that had their nuclear capabilities removed. Leaders within the U.S. Department of Defense, such as Air Force General Anthony Cotton, argue that the nuclear modernization program, as it is called, is a “national imperative.” While some nuclear and foreign policy analysts argue that the program is crucial to building — or rebuilding — a formidable arsenal that deters other nuclear powers, others say it raises questions for both nuclear deterrence and arms control.

Still, the costly and massive nuclear modernization program enjoys bipartisan support, said Geoff Wilson, a defense policy researcher at the Stimson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. “The United States has committed itself to one of the largest arms races in history. We’re spending about $75 billion a year on new nuclear weapons,” he said, citing figures from the Congressional Budget Office. In comparison, the entire Manhattan Project cost about $30 billion in today’s dollars, spread over multiple years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Laurie Anderson’s “Waiting For The Barbarians”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

JK Rowling Clarifies Political Views

Ryan Smith in Newsweek:

Author JK Rowling has clarified her political views after a social media user accused her of having “far-right” sympathies over her views on transgender women. Over the past few years, the Harry Potter writer has sparked debate—and backlash—over her expressed statements on trans women, leading some activists to brand Rowling a “TERF”—an acronym for trans-exclusionary radical feminist.

Author JK Rowling has clarified her political views after a social media user accused her of having “far-right” sympathies over her views on transgender women. Over the past few years, the Harry Potter writer has sparked debate—and backlash—over her expressed statements on trans women, leading some activists to brand Rowling a “TERF”—an acronym for trans-exclusionary radical feminist.

On Sunday, British-born Rowling responded to a person on X, formerly Twitter, who suggested that her politics were more aligned with right-wing ideologies. Newsweek has contacted a representative of Rowling via email for comment. “@jk_rowling is far right,” read the post. “[I don’t care] how many times she pretends she isn’t. She gets all of her information from [neo-Nazi] publications and far-right hate groups. [She] believes a far-right conspiracy theory that is basically just ‘the Protocols of the elders of Zion,’ but for trans [people].”

Sharing a lengthy response, Rowling wrote: “You can keep telling yourself this, but you’re simply wrong. I’m a left-leaning liberal who’s fiercely anti-authoritarian, and if you couldn’t deduce that from my work you haven’t understood a word of it. “I’m not an ideologue. I mistrust ideologies,” she continued.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

This scientist treated her own cancer with viruses she grew in the lab

Zoe Corbin in Nature:

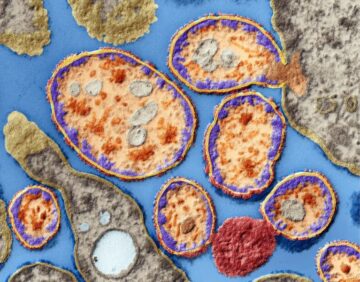

A scientist who successfully treated her own breast cancer by injecting the tumour with lab-grown viruses has sparked discussion about the ethics of self-experimentation. Beata Halassy discovered in 2020, aged 49, that she had breast cancer at the site of a previous mastectomy. It was the second recurrence there since her left breast had been removed, and she couldn’t face another bout of chemotherapy.

A scientist who successfully treated her own breast cancer by injecting the tumour with lab-grown viruses has sparked discussion about the ethics of self-experimentation. Beata Halassy discovered in 2020, aged 49, that she had breast cancer at the site of a previous mastectomy. It was the second recurrence there since her left breast had been removed, and she couldn’t face another bout of chemotherapy.

Halassy, a virologist at the University of Zagreb, studied the literature and decided to take matters into her own hands with an unproven treatment. A case report published in Vaccines in August1 outlines how Halassy self-administered a treatment called oncolytic virotherapy (OVT) to help treat her own stage 3 cancer. She has now been cancer-free for four years. In choosing to self-experiment, Halassy joins a long line of scientists who have participated in this under-the-radar, stigmatized and ethically fraught practice. “It took a brave editor to publish the report,” says Halassy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

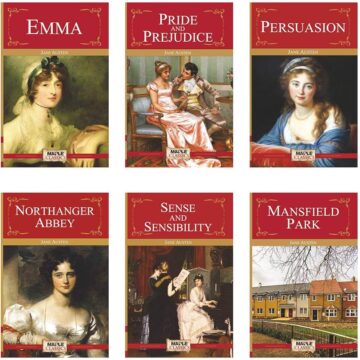

Darwin And Austin On Nature And Beauty

Abigail Tulenko at Aeon Magazine:

Austen’s keen observation extends to her rich aesthetic sensibility. And, yet, beauty figures strangely in a naturalist’s worldview. Darwin, who develops the naturalistic worldview to a new extreme, was deeply troubled by ‘ornament’ in the animal kingdom as a potential threat to his theory of natural selection. In Aesthetics After Darwin (2019), the philosopher Winfried Menninghaus describes Darwin’s decades-long enquiry into ornament as an obsession driven by a central question: how to explain instances of seemingly superfluous beauty within his empirical scientific worldview? In The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin marvels that ‘The development, however, of certain structures’ – such as horns, feathers, and so on – ‘has been carried to a wonderful extreme; and in some cases to an extreme which, as far as the general conditions of life are concerned, must be slightly injurious.’ The peacock’s feathers are superfluous to its biologic fitness; their cumbersome size may actually be antithetical to any one bird’s individual survival. And so their existence seems to fly in the face of naturalistic explanation.

Austen’s keen observation extends to her rich aesthetic sensibility. And, yet, beauty figures strangely in a naturalist’s worldview. Darwin, who develops the naturalistic worldview to a new extreme, was deeply troubled by ‘ornament’ in the animal kingdom as a potential threat to his theory of natural selection. In Aesthetics After Darwin (2019), the philosopher Winfried Menninghaus describes Darwin’s decades-long enquiry into ornament as an obsession driven by a central question: how to explain instances of seemingly superfluous beauty within his empirical scientific worldview? In The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin marvels that ‘The development, however, of certain structures’ – such as horns, feathers, and so on – ‘has been carried to a wonderful extreme; and in some cases to an extreme which, as far as the general conditions of life are concerned, must be slightly injurious.’ The peacock’s feathers are superfluous to its biologic fitness; their cumbersome size may actually be antithetical to any one bird’s individual survival. And so their existence seems to fly in the face of naturalistic explanation.

In his early writings, Darwin ‘conceived of beauty first of all as scandalous excess, as potentially self-destructive luxury,’ writes Menninghaus.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

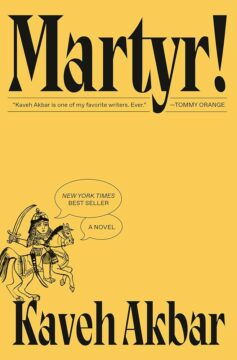

An Interview with Kaveh Akbar

India Ennenga and Kaveh Akbar at The Believer:

BLVR: You’ve said you want to honor all the poets “whose rapturous ecstasy overwhelmed even language’s ability to transcribe it.” Many of those, I imagine, are the authors you included as the editor of The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 110 Poets and the Divine. Spiritual and religious writing offers some of the deepest considerations of the ineffable but feels a little taboo in our increasingly secular culture.

BLVR: You’ve said you want to honor all the poets “whose rapturous ecstasy overwhelmed even language’s ability to transcribe it.” Many of those, I imagine, are the authors you included as the editor of The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 110 Poets and the Divine. Spiritual and religious writing offers some of the deepest considerations of the ineffable but feels a little taboo in our increasingly secular culture.

KA: It’s out of style, certainly. The standard belief is that if you’re smart, you have to be cynical. There’s an equivalency of skepticism with intelligence, and of belief with naivete, which is the height of hubris to me—as if we have suddenly landed upon an intelligence heretofore unavailable to Milton or Rabi’ah.

BLVR: That equivalency makes it easy to forget that spiritual verse is the origin of poetry—indeed, in many cultures there is no distinction whatsoever between poetry and prayer. Would you say that all poetry, even the most contemporary and secular, is still grappling with our earliest concerns of articulating a spiritual ineffability?

KA: In the anthology, I point to Enheduanna, born in 2286 BCE, a female priest who wrote often to the goddess Inanna, as the earliest attributable author in history. She was exiled from the Sumerian city-state of Ur by her brother when her dad, Sargon, died. So she was writing a lot of her hymns from exile, which immediately connected her to Ovid, and to Dante.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, November 10, 2024

It Was Always About Inflation

Doug Henwood in Jacobin:

I often say that the Democrats’ political problem is that they’re a party of capital that has to pretend otherwise for electoral purposes. This time they hardly even pretended. Kamala Harris preferred campaigning with the inexplicably famous mogul Mark Cuban and the ghoulish Liz Cheney to Shawn Fain, who led the United Auto Workers to the greatest strike victory in decades. Those associations telegraphed both her policy instincts and her demographic targeting: Silicon Valley and upscale suburbs.

Like Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, the strategy failed, only worse. At least Clinton won the popular vote by almost three million. Harris even lost among suburban white women, a principal target of this twice-failed strategy.

Like any major historical event, this defeat has many explanations. Preceding her disastrous campaign, there was the bizarre nature of Harris’s nomination. White House staff hid the severity of Joe Biden’s mental decline for his entire presidency, until his disastrous debate performance against Donald Trump made it impossible to sustain the fiction of his competence any longer. There was no primary — not that the Democrats’ talent bench is deep, but it might have helped to have a competitive sorting — and, after a delusional bout of enthusiasm, we were quickly reminded why she crashed as a candidate in 2020.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Donald J. Trump

Peter E. Gordon in Boston Review:

From 2016 to 2020 Donald J. Trump served as forty-fifth president of the United States; now, he has secured his reelection and will assume office once again as president number forty-seven. It was Marx who left us with the memorable claim that events in history occur twice: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” But today this slogan, memorable as it is, surely doesn’t apply, since Trump’s first term was already a farce, distinguished most of all as a spectacle of bluster and boasting that, despite his many plans, left the basic institutions of American democracy more or less intact. He said that he would build a wall across the full two thousand miles of the United States’ southern border and Mexico would pay for it. (His sadistic family separation policy destroyed the lives of thousands, but his administration built only about five hundred miles of the wall, much of it reinforcements to existing barriers, and American taxpayers bore the cost.) He said that he would dismantle the Affordable Care Act and replace it with something better. (He didn’t, and the ACA remains among the most popular achievements of the Obama administration.) He said that he would impose a ban on immigrants from Muslim-majority countries. (He tried, with fitful success, though the courts dogged his efforts.) These promises came to us wrapped in the vacuous slogan that he would “Make America Great Again.” (Great? Hardly. It would be more accurate to say that America became an object of great derision and concern. Especially among our European allies, the fear arose that democracy in America, technically among the oldest democracies in the world, was showing signs of backsliding into autocracy.)

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Exit Right

Gabriel Winant in Dissent:

The most important image of the 2024 election, to my eye, was generated one evening of the Democratic National Convention, when delegates had to file past protesters chanting the names and ages of dead Palestinian children. The attendees did not simply ignore the demonstration, as one might have expected; rather, they exaggeratedly plugged their ears, made mocking faces, and, in one notable case, sarcastically mimicked the chant: “Eighteen years old!” Witnessing video of this event, my heart sank, not just at the moral grotesqueness of the display, but also in its sickening confirmation of the solipsism and complacency of Democratic Party officialdom. The conventiongoers offered a literal enactment of their lack of interest in the experiences of those outside their circle of concern. La-la, I can’t hear you—or, as Kamala Harris herself put it when challenged at a rally, “I am speaking now.” Not for long, as it turned out.

The best moment of the Harris campaign was the very beginning, when she got a chance to embody the collective sigh of relief at Joe Biden’s decision to bow out, and to offer something new. From there, it was all downhill. She and those around her seemed to think that purely superficial changes would prove sufficient. Harris pointedly refused to offer any criticism of the incumbent administration, or even suggest any way in which she differed from it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Judith Jamison (1943 – 2024) Dancer And Choreographer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Linda LaFlamme (1947 – 2024) Musician

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Quincy Jones (1933 – 2024) Music Producer, Arranger, Songwriter, Composer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

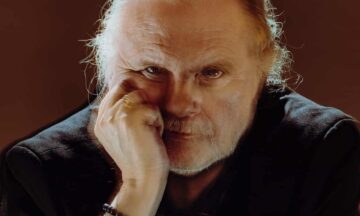

Morning and Evening – the Nobel laureate’s mystical account of where we begin and end

Yagnishsing Dawoor in The Guardian:

The second part, chiefly told from Johannes’s point of view, chronicles the eerie hours after he wakes up one morning, late in his old age. Johannes is a now retired fisherman. His wife, Erna, is long dead. His mornings are “sad and lonely”. Johannes makes coffee. He steps out of the house and everything he beholds seems different somehow. He meets his dead neighbour, and good friend Peter, and they go fishing. Johannes later bumps into his daughter Signe and “is seized with deep despair, because Signe cannot see him or hear him”. At the tale’s close, Peter accompanies Johannes to a place where nothing hurts and “everything you love is there”.

The second part, chiefly told from Johannes’s point of view, chronicles the eerie hours after he wakes up one morning, late in his old age. Johannes is a now retired fisherman. His wife, Erna, is long dead. His mornings are “sad and lonely”. Johannes makes coffee. He steps out of the house and everything he beholds seems different somehow. He meets his dead neighbour, and good friend Peter, and they go fishing. Johannes later bumps into his daughter Signe and “is seized with deep despair, because Signe cannot see him or hear him”. At the tale’s close, Peter accompanies Johannes to a place where nothing hurts and “everything you love is there”.

Fosse has a precious ear for the muted whimpers of grief; there are such depths of ache contained in this brief novel. That we begin the journey of dying as soon as we are born may be one of this book’s most effectively dramatised insights, but it succeeds, no less brilliantly, in conveying late-life pain and melancholia; what the days feel like once friends and lovers are gone and we have but our own vanishing selves for company.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Descending

Jenny Morgan in Harper’s Magazine:

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Pollen of Life

—poem for Jack Micheline

He was the high note of a wailing saxophone

The spark that ignites a fire

He was a fifth of Jack Daniel’s

A glass of imported beer

A shaman

A vagabond poet shuffling words

Like a river-boat gambler

Ravished by illness

Ravished by time

He painted his visions on canvass

In parks in bars and coffee houses

His poems singing out across the

Streets of America

Pure innocence

Pure genius

Spinning words that hung in the air

Like a hummingbird drunk on the

Pollen of life

by A.D. Winan

from Poetic Outlaws

On Jack Micheline here also

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, November 8, 2024

A Social Media Site For The Dead

Tony Ho Tran in Slate:

It’s a good way to spend a Saturday morning—if, admittedly, a strange one. I wake up and pack a tote bag with leather gardening gloves, a water bottle, a towel, and headphones. Then I drive to one of Chicago’s 272 cemeteries and spend hours taking pictures of the dead.

It’s a good way to spend a Saturday morning—if, admittedly, a strange one. I wake up and pack a tote bag with leather gardening gloves, a water bottle, a towel, and headphones. Then I drive to one of Chicago’s 272 cemeteries and spend hours taking pictures of the dead.

I do this once a month or so. Alongside shots of my dog and gym selfies, my phone’s camera roll is filled with photos of gravestones of all shapes, sizes, and materials: massive granite monuments fit for the Chicago industrialists buried underneath them, humble flat markers that I’m prone to tripping over, and sandstone slabs so worn down by centuries of sun, rain, and snow that there’s no telling who’s buried there.

I should say: It’s not just me. The photos I take end up on a website called FindaGrave.com, a repository of cemeteries around the world. Created in 1995 by a Salt Lake City resident named Jim Tipton, the website began as a place to catalog his hobby of visiting and documenting celebrity graves. In the late 1990s, Tipton began to allow other users to contribute their own photos and memorials for famous people as well. In 2010, Find a Grave finally allowed non-celebrities to be included. Since then, volunteers—also known as “gravers”—have stalwartly photographed and recorded tombstones, mausoleums, crosses, statues, and all other manner of graves for posterity.

I should say: It’s not just me. The photos I take end up on a website called FindaGrave.com, a repository of cemeteries around the world. Created in 1995 by a Salt Lake City resident named Jim Tipton, the website began as a place to catalog his hobby of visiting and documenting celebrity graves. In the late 1990s, Tipton began to allow other users to contribute their own photos and memorials for famous people as well. In 2010, Find a Grave finally allowed non-celebrities to be included. Since then, volunteers—also known as “gravers”—have stalwartly photographed and recorded tombstones, mausoleums, crosses, statues, and all other manner of graves for posterity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Rock-Star Researcher Spun a Web of Lies—and Nearly Got Away with It

Sarah Treleaven at The Walrus:

Laskowski revealed that her ambition had drawn her into the web of prolific spider researcher Jonathan Pruitt, a behavioural ecologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Pruitt was a superstar in his field and, in 2018, was named a Canada 150 Research Chair, becoming one of the younger recipients of the prestigious federal one-time grant with funding of $350,000 per year for seven years. He amassed a huge number of publications, many with surprising and influential results. He turned out to be an equally prolific fraud.

Laskowski revealed that her ambition had drawn her into the web of prolific spider researcher Jonathan Pruitt, a behavioural ecologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Pruitt was a superstar in his field and, in 2018, was named a Canada 150 Research Chair, becoming one of the younger recipients of the prestigious federal one-time grant with funding of $350,000 per year for seven years. He amassed a huge number of publications, many with surprising and influential results. He turned out to be an equally prolific fraud.

When Pruitt’s other colleagues and co-authors became aware of misrepresentations and outright falsifications in his body of work, they pushed for their own papers co-authored with him to be retracted one by one. But as they would soon learn, making an honest man of Pruitt would be an impossible task.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Subhan Ahmed Nizami & Brothers: Aaeen Kyoon Hichkiyaan Nahin Maloom

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It’s time for sobriety, not denial

Damon Linker in Persuasion:

The results this time weren’t, to put it in poker terms, a rare inside straight easily manipulable by nefarious forces. Trump gained ground in nearly every corner of the country, among nearly every segment of the electorate.

The results this time weren’t, to put it in poker terms, a rare inside straight easily manipulable by nefarious forces. Trump gained ground in nearly every corner of the country, among nearly every segment of the electorate.

Which means Trump has real and broad-based support. Does some of that support come from fervent racists and xenophobes and sexists? I’m sure it does. Just as undoubtedly the outright fascists and neo-Nazis are thrilled by his win. But there are many more Americans who voted for him for other reasons.

It is a fallacy to believe that the thing you see in and hate about a politician is inevitably reflected in those who vote for him or her. That’s why I was so critical of Harris for closing her campaign by pushing the line that Trump is a fascist—because it implied that those entertaining a vote for him were fascists themselves. Some small number of people might have responded to that by thinking, “why yes, I am, and thanks for noticing.” But far more probably found the suggestion outrageous, condescending, and insulting.

It’s time for the political and intellectual opposition to Trumpism to move forward—soberly, intelligently, with a level head, and in full awareness of just how big Donald Trump’s achievement really is.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.