Adam Gopnik at The New Yorker:

Adam Gopnik at The New Yorker:

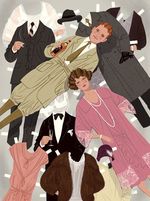

Second acts there may or may not be, but American epilogues go on forever. Scott and Zelda’s friends from the Jazz Age would doubtless have spit up into their morning coffee—or, more likely, into teacups filled with bathtub gin—to find the pair, almost a century after their meeting, not a poignant footnote to an ill-named time but an enduring legend of the West, a subject adaptable for movies and novels and probably paper dolls and ice shows. Already by the late fifties, the critic Edmund Wilson, who had known Fitzgerald since their Princeton years and had the exasperated affection mingled with disdain that we have for old friends who become famous, had marvelled that Fitzgerald in death had become a variant of the Adonis of Greek myth, taking on “the aspect of a martyr, a sacrificial victim, a semi-divine personage.” Wilson, who served Fitzgerald beautifully as a literary executor, thought it was absurd that his drunken, often silly college friend could become a dying-and-reviving god—which is surely how Dylan Thomas’s and Percy Shelley’s friends felt about a similar transformation in those afterlives, and doubtless how Adonis’ friends felt about him, too.

And here we are, in another season, with more new books that are in one way or another new treatments of the Fitzgerald myth: Zelda and Scott courting, Zelda and Scott in New York frolicking in the Plaza fountain, Zelda and Scott in the South of France taking lovers and the sun, and, finally, both of them bereft and alone, she in a sanatorium in North Carolina, he in the Garden of Allah hotel, in Hollywood.

more here.