by Jonathan Kujawa

Invicta by Robert Lang

Last time at 3QD we talked about constructible numbers. We followed in the footsteps of the ancient Greeks and asked what sorts of numbers we can get as the lengths of line segments made using only a compass and straightedge. In the end we found that starting with a line segment of length one, a compass and straightedge, and enough patience, we can make any rational number, the square root of any rational number, and, indeed, any number which can be made by a finite sequences of additions, subtractions, multiplications, divisions, and square roots. Even crazy numbers like √(13/2 +14.3(√7)) are constructible. In short, compass and straightedge constructions are equivalent to being able to solve arbitrary quadratic equations.

On the other hand, that's it. Logarithms, exponentials, π, and even the roots of higher powers are all impossible. No matter how hard we try, the cubed root of 2 is not constructible. The 2000-year-old challenge to double the cube is forever out of reach.

An ellipse (from Wikipedia).

But, of course, this all depends on our initial decision to only allow a compass and straightedge. If you also gave me two pins and a string I could use them to make an ellipse. "So what?", you say. After all, what does the ability to draw an ellipse buy you? Well, it has been known for centuries that you can double the cube and trisect the angle if you are allowed to use parabolas and hyperbolas. In 1997 Carlos Videla determined exactly which numbers are constructible using a straightedge and the conics (circles, ellipses, hyperbolas, and parabolas). In short, the addition of the conics allows you to take cube roots. No more, no less. Remarkably, in 2003 Patrick Hummel proved that the hyperbolas and parabolas are redundant. Every number you can construct using a straightedge and the conics can be constructed with just the compass, straightedge, and ellipses. Give me an ellipse and I'll solve your cubic equation!

Of course, this is all very Euro-centric. We use the compass, straightedge, and conics because we are in the Western tradition and that's what the Greeks used.

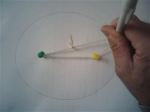

But what about those of us who grew up in Japan? There the ancient geometric tradition is origami. We could just as well ask which numbers are constructible using paper folding. We can make a straight line in the form of the crease made when we fold the paper. If two creases intersect, this makes a point. If we've made two points, we can make the straight line which connects them by folding a crease through the points. Since we can make lines and points, we can say a number is origami-constructible if we can start with a one by one sheet of paper and use paper folding to make a line segment of that length; much like we did for the compass and straightedge.

Which numbers are origami-constructible?

Surprisingly, despite the centuries of effort in understanding the mathematics of Greek geometry, the mathematics of origami has only really taken off in the past few decades. Nevertheless, lots of progress has been made!

Read more »

These days I’m reflecting a lot on what a compassionate system would be. People generally know too little about systems, let alone about science. That’s one reason the current government may get away with enormous cuts to science.