Matt Seybold in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Tired and slightly toasted after a long and draining dinner party, Virginia Woolf nevertheless kept a promise to her diary, recording her impression of the evening while it was still fresh. Fellow novelist Elizabeth Bowen arrived very late — “rayed like a zebra, silent and stuttering” — leaving Woolf the lone woman at a table ringed with notoriously self-assured men. This, combined with her fatigue, may explain why her account of their conversation was curt and occasionally cruel. T. S. Eliot, she wrote, was “like a great toad with jeweled eyes.” Her nephew, poet Julian Bell, was “trivial: like dogs in their lusts.” Even John Maynard Keynes, for whom she held an enduring affection, she portrayed on this occasion as bloviating and hypocritical. After mocking Christian rituals, Keynes, perhaps lightly lubricated himself, reminisced at length about a chapel ceremony held in his honor at King’s College. Woolf’s question — “Did this society, this coming together move [you?]” — is the elocutionary equivalent of an exasperated eye-roll. [1]

Tired and slightly toasted after a long and draining dinner party, Virginia Woolf nevertheless kept a promise to her diary, recording her impression of the evening while it was still fresh. Fellow novelist Elizabeth Bowen arrived very late — “rayed like a zebra, silent and stuttering” — leaving Woolf the lone woman at a table ringed with notoriously self-assured men. This, combined with her fatigue, may explain why her account of their conversation was curt and occasionally cruel. T. S. Eliot, she wrote, was “like a great toad with jeweled eyes.” Her nephew, poet Julian Bell, was “trivial: like dogs in their lusts.” Even John Maynard Keynes, for whom she held an enduring affection, she portrayed on this occasion as bloviating and hypocritical. After mocking Christian rituals, Keynes, perhaps lightly lubricated himself, reminisced at length about a chapel ceremony held in his honor at King’s College. Woolf’s question — “Did this society, this coming together move [you?]” — is the elocutionary equivalent of an exasperated eye-roll. [1]

The dinner was held explicitly to discuss Eliot’s After Strange Gods: A Primer of Modern Heresy (1934), which collected a series of lectures given the previous year at University of Virginia. Keynes, at the time among Britain’s most prominent public intellectuals, was preparing for his own trip to the United States, during which he would reassert himself as an “economic heretic” and preview his work-in-progress, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936). Eliot had recently conceded that they were living “in the age of the economist” when even poets were “compelled to think about economics,” so it was, perhaps, inevitable that the discussion would turn after dinner to what Woolf called “the economic question.” “This worst of all,” she wrote, “and founded on a silly mistake of old Mr. Ricardo’s which Maynard given time will put right. And then there will be no more economic stress, and then — ?”

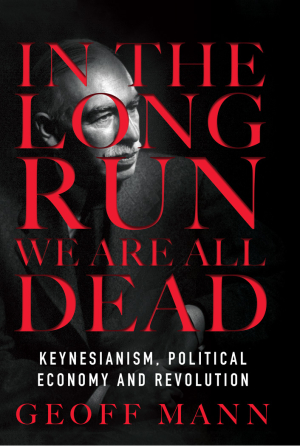

It is hard to know how to read this lacuna in Woolf’s account. Is her faith that Keynes could eliminate “economic stress” sincere or sarcastic? Is she reflecting Keynes’s own ambivalence about utopian prognostications? In either case, her impression that Keynes was working on an audacious political economy designed to save the world from audacious political economy perfectly encapsulates a central paradox of Keynesianism, as elucidated by Geoff Mann’s In The Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy and Revolution (2017). Keynes expected The General Theoryto radically remake his profession, though not in the ways Mann demonstrates it has. In Mann’s account, Keynesianism ultimately helped sever economists from their own rich tradition of heretical political philosophy and reduced them to platitudinous apologists for plutocracy.

More here.