Dana Gioia at First Things:

The English poet Elizabeth Jennings had the peculiar fate of being in the right place at the right time in the wrong way. Her career began splendidly. Her verse appeared in prominent journals, championed by Oxford’s new generation of tastemakers. Her first publication, Poems (1953), launched the acclaimed Fantasy Poets pamphlet series, which would soon present the early work of Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, Thom Gunn, and Geoffrey Hill. Her first full-length collection, A Way of Looking (1955), won the Somerset Maugham Award and became the Poetry Book Society recommendation. She was the youngest poet featured in the first Penguin Modern Poets volume (1962). Meanwhile Jennings achieved enduring notoriety as the only female member of “The Movement,” the irreverent and contrarian group that dominated mid-century British poetry. By age thirty, Jennings was a celebrated writer.

“To be lucky in the beginning is everything,” claimed Cervantes, but Jennings’s luck did not hold. In the great expansion of universities and literary publishing following World War II, her Movement peers gained academic appointments, lucrative book deals, and critical esteem. Jennings’s career stalled. Her fame as a Movement poet proved a dead end. She never belonged in that Oxbridge boys’ club. She shared The Movement’s commitment to clarity and traditional form, but her politics were to the left of their mostly conservative stance.

more here.

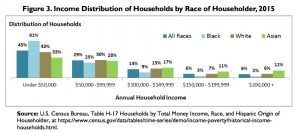

Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!”

Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!” Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”

Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.” Outside the kitchen door at the Kuala Belalong Field Studies Center in Brunei, on a number of trees near the balcony, there is a nest of very special ants. They explode.

Outside the kitchen door at the Kuala Belalong Field Studies Center in Brunei, on a number of trees near the balcony, there is a nest of very special ants. They explode.