Ezra Klein in Vox:

In 2008, Barack Obama held up change as a beacon, attaching to it another word, a word that channeled everything his young and diverse coalition saw in his rise and their newfound political power: hope. An America that would elect a black man president was an America in which a future was being written that would read thrillingly different from our past. In 2016, Donald Trump wielded that same sense of change as a threat; he was the revanchist voice of those who yearned to make America the way it was before, to make it great again. That was the impulse that connected the wall to keep Mexicans out, the ban to keep Muslims away, the birtherism meant to prove Obama couldn’t possibly be a legitimate president. An America that would elect Donald Trump president was an America in which a future was being written that could read thrillingly similar to our past. This is the core cleavage of our politics, and it reflects the fundamental reality of our era: America is changing, and fast. According to the Census Bureau, 2013 marked the first yearthat a majority of US infants under the age of 1 were nonwhite. The announcement, made during the second term of the nation’s first African-American president, was not a surprise. Demographers had been predicting such a tipping point for years, and they foresaw more to come.

In 2008, Barack Obama held up change as a beacon, attaching to it another word, a word that channeled everything his young and diverse coalition saw in his rise and their newfound political power: hope. An America that would elect a black man president was an America in which a future was being written that would read thrillingly different from our past. In 2016, Donald Trump wielded that same sense of change as a threat; he was the revanchist voice of those who yearned to make America the way it was before, to make it great again. That was the impulse that connected the wall to keep Mexicans out, the ban to keep Muslims away, the birtherism meant to prove Obama couldn’t possibly be a legitimate president. An America that would elect Donald Trump president was an America in which a future was being written that could read thrillingly similar to our past. This is the core cleavage of our politics, and it reflects the fundamental reality of our era: America is changing, and fast. According to the Census Bureau, 2013 marked the first yearthat a majority of US infants under the age of 1 were nonwhite. The announcement, made during the second term of the nation’s first African-American president, was not a surprise. Demographers had been predicting such a tipping point for years, and they foresaw more to come.

White voters who feel they are losing a historical hold on power are reacting to something real. For the bulk of American history, you couldn’t win the presidency without winning a majority — usually an overwhelming majority — of the white vote. Though this changed before Obama (Bill Clinton won slightly less of the white vote than his Republican challengers), the election of an African-American president leading a young, multiracial coalition made the transition stark and threatening. This is the crucial context for Trump’s rise, and it’s why Tesler has little patience for those who treat Trump as an invader in the Republican Party. In a field of Republicans who were trying to change the party to appeal to a rising Hispanic electorate, Trump was alone in speaking to Republican voters who didn’t want the party to remake itself, who wanted to be told that a wall could be built and things could go back to the way they were. “Trump met the party where it was rather than trying to change it,“ Tesler says. “He was hunting where the ducks were.”

More here. (Note: Thanks to Jehanzeb Kayani)

Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

Adam Kirsch in The Nation:

Ferdinand Mount in the LRB:

Ferdinand Mount in the LRB:

Alzheimer’s disease has long been considered an inevitable consequence of ageing that is exacerbated by a genetic predisposition. Increasingly, however, it is thought to be influenced by modifiable lifestyle behaviours that might enable a person’s risk of developing the condition to be controlled. But even as evidence to support this idea has accumulated over the past decade, the research community has been slow to adopt the idea. This reluctance was obvious as recently as 2010, when the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) brought together a panel of 15 researchers to consider the state of research on preventing Alzheimer’s disease, at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland. Tantalizing findings had begun to emerge that suggested that behavioural choices such as engaging in physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and healthy eating could reduce the risk of brain degeneration. In a 2006 study

Alzheimer’s disease has long been considered an inevitable consequence of ageing that is exacerbated by a genetic predisposition. Increasingly, however, it is thought to be influenced by modifiable lifestyle behaviours that might enable a person’s risk of developing the condition to be controlled. But even as evidence to support this idea has accumulated over the past decade, the research community has been slow to adopt the idea. This reluctance was obvious as recently as 2010, when the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) brought together a panel of 15 researchers to consider the state of research on preventing Alzheimer’s disease, at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland. Tantalizing findings had begun to emerge that suggested that behavioural choices such as engaging in physical exercise, intellectual stimulation and healthy eating could reduce the risk of brain degeneration. In a 2006 study You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “

You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “ If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “

If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “ It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct?

It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct? Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification.

Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification. To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street.

To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street. Sunday, late July: the small suburban towns of Persan and Beaumont-sur-l’Oise are almost empty. Persan, the last stop on the H line, is half an hour from the Gare du Nord, through a landscape of woodland and fields. It was a beautiful day. A man was fishing by the banks of the Oise; two others were chatting in front of a hairdresser’s salon. The day before, thousands of people from Paris and the banlieues had filled the streets; some had arrived by bus from further afield, among them party leaders from the left-wing NPA and La France Insoumise, anti-racist activists, relatives of people who had been killed by the police, girls wearing T-shirts saying ‘Justice for Adama’ or ‘Justice for Gaye’, and a man with a placard: ‘The State protects Benallas, we want to save Adamas.’

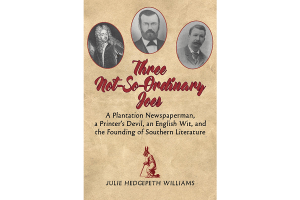

Sunday, late July: the small suburban towns of Persan and Beaumont-sur-l’Oise are almost empty. Persan, the last stop on the H line, is half an hour from the Gare du Nord, through a landscape of woodland and fields. It was a beautiful day. A man was fishing by the banks of the Oise; two others were chatting in front of a hairdresser’s salon. The day before, thousands of people from Paris and the banlieues had filled the streets; some had arrived by bus from further afield, among them party leaders from the left-wing NPA and La France Insoumise, anti-racist activists, relatives of people who had been killed by the police, girls wearing T-shirts saying ‘Justice for Adama’ or ‘Justice for Gaye’, and a man with a placard: ‘The State protects Benallas, we want to save Adamas.’ On the surface, the new book by Julie Hedgepeth Williams, Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes, is the story of the long and winding genesis of literary culture in the post-Civil War American South. One of the “not-so-ordinary Joes” referred to in the title is, after all, Joel Chandler Harris (whose childhood nickname was Joe), author of the Uncle Remus stories that sold astoundingly well both in postwar America and around the world and influenced an entire generation of writers, playing a large role in creating a distinctive Southern literary tradition. But in addition to that surface story, there’s also a deeper narrative thread winding its way through “Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes,” a narrative about the unpredictable, often byzantine connections that thread their way from one literary generation to another. In this case, Williams quite delightfully traces this thread through the same name, linking two generations of 19th-century American Southerners with a namesake from 18th-century England, a man who never knew anything about either of them or about the American South itself.

On the surface, the new book by Julie Hedgepeth Williams, Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes, is the story of the long and winding genesis of literary culture in the post-Civil War American South. One of the “not-so-ordinary Joes” referred to in the title is, after all, Joel Chandler Harris (whose childhood nickname was Joe), author of the Uncle Remus stories that sold astoundingly well both in postwar America and around the world and influenced an entire generation of writers, playing a large role in creating a distinctive Southern literary tradition. But in addition to that surface story, there’s also a deeper narrative thread winding its way through “Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes,” a narrative about the unpredictable, often byzantine connections that thread their way from one literary generation to another. In this case, Williams quite delightfully traces this thread through the same name, linking two generations of 19th-century American Southerners with a namesake from 18th-century England, a man who never knew anything about either of them or about the American South itself. It’s harder than you might think to make a dinosaur. In Jurassic Parkthey do it by extracting a full set of dinosaur DNA from a mosquito preserved in amber, and then cloning it. But DNA degrades over time, and to date none has been found in a prehistoric mosquito or a dinosaur fossil. The more realistic prospect is to take a live dinosaur you have lying around already: a bird. Modern birds are considered a surviving line of theropod dinosaurs, closely related to the T rex and velociraptor. (Just look at their feet: “theropod” means “beast-footed”.) By tinkering with how a bird embryo develops, you can silence some of its modern adaptations and let the older genetic instructions take over. Enterprising researchers have already

It’s harder than you might think to make a dinosaur. In Jurassic Parkthey do it by extracting a full set of dinosaur DNA from a mosquito preserved in amber, and then cloning it. But DNA degrades over time, and to date none has been found in a prehistoric mosquito or a dinosaur fossil. The more realistic prospect is to take a live dinosaur you have lying around already: a bird. Modern birds are considered a surviving line of theropod dinosaurs, closely related to the T rex and velociraptor. (Just look at their feet: “theropod” means “beast-footed”.) By tinkering with how a bird embryo develops, you can silence some of its modern adaptations and let the older genetic instructions take over. Enterprising researchers have already