Anjuli Raza Fatima Kolb at the Poetry Foundation:

I’m not one to go digging around in old dirt, but sometimes you find good bones. Recently I’ve been doing some research in the papers of an important scholar and public intellectual who taught at my university and died on my twenty-second birthday. When he died, I was a baby editor, and bad at my job, but I felt a little grand. I managed to get the day off from work for the memorial and bought a prim looking black dress from Goodwill, linen with a satin ribbon. I dug out my interview heels. People like Noam Chomsky said very moving things, but I couldn’t pay attention. The shape of everyone’s grief was so different and it didn’t really make sense to me. Everyone took his death personally, and the obituary in the Times was less than totally respectful.

I’m not one to go digging around in old dirt, but sometimes you find good bones. Recently I’ve been doing some research in the papers of an important scholar and public intellectual who taught at my university and died on my twenty-second birthday. When he died, I was a baby editor, and bad at my job, but I felt a little grand. I managed to get the day off from work for the memorial and bought a prim looking black dress from Goodwill, linen with a satin ribbon. I dug out my interview heels. People like Noam Chomsky said very moving things, but I couldn’t pay attention. The shape of everyone’s grief was so different and it didn’t really make sense to me. Everyone took his death personally, and the obituary in the Times was less than totally respectful.

Since eye and mind were wandery—like when you’ve crashed a party—I stared and tried to stay very still. I followed the lines of heavy stone to the grand but unbeautiful ceiling, traced the bronchioles of the organ, blinked in slowmo to feel the quiet hubbub, and tried to remember who told me about Alice Babs singing there, in Riverside Church or was it St. John the Divine, and what was supposed to have been shocking about it.

These are hard times for theoryTM, the summer bookended by revelations of a scandal that has split my social world down the middle, largely along generational lines. One of the theorists weighing in—who has signed a letter suggesting that reputation and clout, “grace” and “wit” should be allowed to eclipse abuse—wrote recently “I am still against scandal culture.” It’s probably true that there’s more than a little schadenfreude involved in this #moment. The internet is interested in juicy shit, and this is soggy-ass laundry from an out-of-touch cadre on the intellectual left.

But when Derrida died, and Said died, it’s not like the public was more earnestly interested in what they were up to. People hate theory.

More here.

These stories are family sagas writ short, a form Eisenberg may well have invented. The word saga generally brings to mind giant, beach-sandy paperbacks, like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude—not short stories, not even long short stories. Stories don’t in principle have the space to unfurl lifetimes, multiple settings, formation and reverberation. Yet Eisenberg’s stories— with their telescoping time lines and surprising associative turns—expand, even in their ellipses. “Hang on,” thinks young Adam in “Recalculating,” as he considers the earth’s revolution, the chance of it spinning off its axis. “Adam clung to some bits of stubble and closed his eyes. Hang on, he thought, as the Earth gained speed and spun recklessly into the night—hang on, hang on, hang on!” Because Adam is young, his imagination is terrifyingly vivid, and life around him will spin out of control. He will find purchase on stubble in unexpected places, like the girl seeking facts in “Cross Off and Move On.” There is so much living and expression these characters (small and large) bring to the page, lest anyone forget the amplitude.

These stories are family sagas writ short, a form Eisenberg may well have invented. The word saga generally brings to mind giant, beach-sandy paperbacks, like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude—not short stories, not even long short stories. Stories don’t in principle have the space to unfurl lifetimes, multiple settings, formation and reverberation. Yet Eisenberg’s stories— with their telescoping time lines and surprising associative turns—expand, even in their ellipses. “Hang on,” thinks young Adam in “Recalculating,” as he considers the earth’s revolution, the chance of it spinning off its axis. “Adam clung to some bits of stubble and closed his eyes. Hang on, he thought, as the Earth gained speed and spun recklessly into the night—hang on, hang on, hang on!” Because Adam is young, his imagination is terrifyingly vivid, and life around him will spin out of control. He will find purchase on stubble in unexpected places, like the girl seeking facts in “Cross Off and Move On.” There is so much living and expression these characters (small and large) bring to the page, lest anyone forget the amplitude. In the Realm of Perfection dismisses this conventional wisdom and insists that we engage McEnroe on another plane altogether. The inquiry begins in our bemusement at the man-child. When McEnroe interrupts a match to vent, when he spits profane and acid mockery at line judges and referees, when he taunts fans or takes a swat at a photographer with his racquet—the crowd booing lustily—his matches approach the spectacle of professional wrestling, with its travesty of villainy. Why would a player aspire to that?

In the Realm of Perfection dismisses this conventional wisdom and insists that we engage McEnroe on another plane altogether. The inquiry begins in our bemusement at the man-child. When McEnroe interrupts a match to vent, when he spits profane and acid mockery at line judges and referees, when he taunts fans or takes a swat at a photographer with his racquet—the crowd booing lustily—his matches approach the spectacle of professional wrestling, with its travesty of villainy. Why would a player aspire to that? So began a utopian experiment in direct democracy, especially remarkable in Mexico’s authoritarian culture, where vertical hierarchies prevailed socially and politically. The encounter between classes was a mutual education: history and theory in exchange for street smarts and live contact with the country’s social problems. As told to Elena Poniatowska for her collection of testimonies Massacre in Mexico(1971; see also the TLS, May 4, 2018), the university students felt duty-bound to enlighten the polytechnicians, droning on about Lenin, Marcuse and imperialism. Impatient IPN delegates would shout out “¡Concretito!”, “Nuts and bolts! Who’s got tomorrow’s posters?” CNH assemblies also saw heated disagreement about tactics and clashes between those of differing political affiliations. The overarching demand for greater civic participation meant the crucial work of consciousness-raising took place in the streets and slums. The IPN was at the forefront of the roving brigadas with their loudspeakers, xeroxed leaflets and newspapers shoved through bus and car windows, and their street theatre and speak-ins that attracted sympathetic crowds and gave people the chance to voice their own complaints.

So began a utopian experiment in direct democracy, especially remarkable in Mexico’s authoritarian culture, where vertical hierarchies prevailed socially and politically. The encounter between classes was a mutual education: history and theory in exchange for street smarts and live contact with the country’s social problems. As told to Elena Poniatowska for her collection of testimonies Massacre in Mexico(1971; see also the TLS, May 4, 2018), the university students felt duty-bound to enlighten the polytechnicians, droning on about Lenin, Marcuse and imperialism. Impatient IPN delegates would shout out “¡Concretito!”, “Nuts and bolts! Who’s got tomorrow’s posters?” CNH assemblies also saw heated disagreement about tactics and clashes between those of differing political affiliations. The overarching demand for greater civic participation meant the crucial work of consciousness-raising took place in the streets and slums. The IPN was at the forefront of the roving brigadas with their loudspeakers, xeroxed leaflets and newspapers shoved through bus and car windows, and their street theatre and speak-ins that attracted sympathetic crowds and gave people the chance to voice their own complaints. Hold tight. Because I’m now going to try to explain what I think is happening in

Hold tight. Because I’m now going to try to explain what I think is happening in  One part of the Hippocratic Oath, the vow taken by physicians, requires us to “remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” When I, along with my medical school class, recited that oath at my white coat ceremony a year ago, I admit that I was more focused on the biomedical aspects than the “art.” I bought into the mechanism of insulin lowering blood sugar. I bought into the concept of diabetes-induced kidney damage. I bought into the idea of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with diabetes. But art’s—poetry’s—role in the modern practice of medicine? I’ve changed my mind. Physicians are beginning to understand that the role of language and human expression in medicine extends beyond that horizon of uncertainty where doctor and patient must speak to each other about a course of treatment. The restricted language of blood oxygen levels, drug protocols, and surgical interventions may conspire against understanding between doctor and patient—and against healing. As doctors learn to communicate beyond these restrictions, they are reaching for new tools—like poetry.

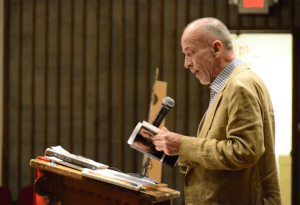

One part of the Hippocratic Oath, the vow taken by physicians, requires us to “remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” When I, along with my medical school class, recited that oath at my white coat ceremony a year ago, I admit that I was more focused on the biomedical aspects than the “art.” I bought into the mechanism of insulin lowering blood sugar. I bought into the concept of diabetes-induced kidney damage. I bought into the idea of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with diabetes. But art’s—poetry’s—role in the modern practice of medicine? I’ve changed my mind. Physicians are beginning to understand that the role of language and human expression in medicine extends beyond that horizon of uncertainty where doctor and patient must speak to each other about a course of treatment. The restricted language of blood oxygen levels, drug protocols, and surgical interventions may conspire against understanding between doctor and patient—and against healing. As doctors learn to communicate beyond these restrictions, they are reaching for new tools—like poetry. Mike Davis didn’t write his first book until his forties. He was too busy doing other things, from working in a slaughterhouse to running the Communist Party’s bookshop in Los Angeles (until he, an inveterate Trotskyist, threw out the Soviet cultural attaché). His late start as a scholar, however, has been compensated for by a deep reservoir of experiences to draw from and a swift pen: since writing his first book in 1986, he has published twenty more.

Mike Davis didn’t write his first book until his forties. He was too busy doing other things, from working in a slaughterhouse to running the Communist Party’s bookshop in Los Angeles (until he, an inveterate Trotskyist, threw out the Soviet cultural attaché). His late start as a scholar, however, has been compensated for by a deep reservoir of experiences to draw from and a swift pen: since writing his first book in 1986, he has published twenty more. For millennia, humanity’s one-and-only reliable way to keep time was based on the Sun. Over the course of a year, the Sun, at any location on Earth, would follow a predictable pattern and path through the sky. Sundials, no more sophisticated than a vertical stick hammered into the ground, were the best timekeeping devices available to our ancestors.

For millennia, humanity’s one-and-only reliable way to keep time was based on the Sun. Over the course of a year, the Sun, at any location on Earth, would follow a predictable pattern and path through the sky. Sundials, no more sophisticated than a vertical stick hammered into the ground, were the best timekeeping devices available to our ancestors. With more than 2 million copies in print, Howard Zinn’s

With more than 2 million copies in print, Howard Zinn’s  Some memories spring into focus with the unimpeachable clarity of first-hand experience and others flicker around the edges of such clarity in such a manner as to suggest that they aren’t really one’s own recollections but rather variable mental reconstructions of things one has heard, things that however second hand nonetheless made so deep an impression that they feel first hand, earned. Years ago, when I was teaching at the Studio School on Eighth Street, I seem to recall having crossed Washington Square and noticing a man intently making $10 sketch portraits on a French easel of any and all comers.

Some memories spring into focus with the unimpeachable clarity of first-hand experience and others flicker around the edges of such clarity in such a manner as to suggest that they aren’t really one’s own recollections but rather variable mental reconstructions of things one has heard, things that however second hand nonetheless made so deep an impression that they feel first hand, earned. Years ago, when I was teaching at the Studio School on Eighth Street, I seem to recall having crossed Washington Square and noticing a man intently making $10 sketch portraits on a French easel of any and all comers. Ten days after a white supremacist carried a gun into a black Charleston church, I was in Los Angeles, listening to a black minister preach about the end of the world. A coincidence of timing, maybe, although the message seemed apt. What could be more apocalyptically evil than a racist massacre within the hallowed walls of a church, an angry young man sitting through a Bible study before slaughtering the nine strangers who had invited him in to pray? Yet on that Sunday, when the pastor talked about the end, he did not mention Charleston or the seven black churches that had been burned throughout the South in the immediate aftermath. Instead, he spoke about fornication. “M-hm,” a woman behind me chimed in, “and gay marriage.” The ladies beside her murmured their assent. Just the day before, the Supreme Court had legalized same-sex marriage, a decision that seemed to disturb the congregation more than anything that had happened in Charleston. I didn’t understand it. How could marriage equality be a sign of the impending apocalypse, but not a church shooting? How could the evils of fornication be a more pressing topic than the wave of racial violence affecting the very congregation sitting in the pews?

Ten days after a white supremacist carried a gun into a black Charleston church, I was in Los Angeles, listening to a black minister preach about the end of the world. A coincidence of timing, maybe, although the message seemed apt. What could be more apocalyptically evil than a racist massacre within the hallowed walls of a church, an angry young man sitting through a Bible study before slaughtering the nine strangers who had invited him in to pray? Yet on that Sunday, when the pastor talked about the end, he did not mention Charleston or the seven black churches that had been burned throughout the South in the immediate aftermath. Instead, he spoke about fornication. “M-hm,” a woman behind me chimed in, “and gay marriage.” The ladies beside her murmured their assent. Just the day before, the Supreme Court had legalized same-sex marriage, a decision that seemed to disturb the congregation more than anything that had happened in Charleston. I didn’t understand it. How could marriage equality be a sign of the impending apocalypse, but not a church shooting? How could the evils of fornication be a more pressing topic than the wave of racial violence affecting the very congregation sitting in the pews? One of the pleasures of reading critic and fiction writer Yahya Haqqi’s essays in Arabic is that I am always astonished by the breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his experience, the nimbleness of his mind and his eloquence. In the collection Crying, Then Smiling, he has a number of eulogies, one of which is for his uncle, Mahmoud Taher Haqqi, who wrote the first Egyptian novel, The Maidens of Denshawi, about the tragedy of Denshawi in 1906 where British soldiers carelessly killed a villager while they were shooting pigeons—the incident ended tragically when villagers were rounded up and executed by the British. Haqqi points out that it was the first novel to focus on fellaheen, peasants, and their problems and opened the way for Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s novel, Zeyneb (1913). Haqqi wrote that his heart trembled when he read The Maidens of Denshawi—which is what good stories should bring about. Haqqi deserves a eulogy, much like the ones he so generously wrote for others, about his place in Egyptian literary heritage. This seems appropriate in light of the recent celebration of the classic black and white film Al-Bostagy, or The Postman, directed by Husayn Kamal (1968), featuring Shukry Sarhan, based on Haqqi’s novella. But one cannot write about this poignant film without mentioning Sabri Moussa, the talented novelist who translated the spirit of Yahya Haqqi’s novella into a suspenseful screenplay. (He also wrote the screenplay for Yahya Haqqi’s Om Hashem’s Lamp.) Sabri Moussa, who died recently, January 2018, deserves a eulogy as well for his film scripts, short fiction, and novels—the unusual sci-fi tale The Man Arrived from the Spinach Field, the mythic fable

One of the pleasures of reading critic and fiction writer Yahya Haqqi’s essays in Arabic is that I am always astonished by the breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his experience, the nimbleness of his mind and his eloquence. In the collection Crying, Then Smiling, he has a number of eulogies, one of which is for his uncle, Mahmoud Taher Haqqi, who wrote the first Egyptian novel, The Maidens of Denshawi, about the tragedy of Denshawi in 1906 where British soldiers carelessly killed a villager while they were shooting pigeons—the incident ended tragically when villagers were rounded up and executed by the British. Haqqi points out that it was the first novel to focus on fellaheen, peasants, and their problems and opened the way for Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s novel, Zeyneb (1913). Haqqi wrote that his heart trembled when he read The Maidens of Denshawi—which is what good stories should bring about. Haqqi deserves a eulogy, much like the ones he so generously wrote for others, about his place in Egyptian literary heritage. This seems appropriate in light of the recent celebration of the classic black and white film Al-Bostagy, or The Postman, directed by Husayn Kamal (1968), featuring Shukry Sarhan, based on Haqqi’s novella. But one cannot write about this poignant film without mentioning Sabri Moussa, the talented novelist who translated the spirit of Yahya Haqqi’s novella into a suspenseful screenplay. (He also wrote the screenplay for Yahya Haqqi’s Om Hashem’s Lamp.) Sabri Moussa, who died recently, January 2018, deserves a eulogy as well for his film scripts, short fiction, and novels—the unusual sci-fi tale The Man Arrived from the Spinach Field, the mythic fable

The human gut is lined with more than 100 million nerve cells—it’s practically a brain unto itself. And indeed, the gut actually talks to the brain, releasing hormones into the bloodstream that, over the course of about 10 minutes, tell us how hungry it is, or that we shouldn’t have eaten an entire pizza. But a new study reveals the gut has a much more direct connection to the brain through a neural circuit that allows it to transmit signals in mere seconds. The findings could lead to new treatments for obesity, eating disorders, and even depression and autism—all of which have been linked to a malfunctioning gut. The study reveals “a new set of pathways that use gut cells to rapidly communicate with … the brain stem,” says Daniel Drucker, a clinician-scientist who studies gut disorders at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, who was not involved with the work. Although many questions remain before the clinical implications become clear, he says, “This is a cool new piece of the puzzle.”

The human gut is lined with more than 100 million nerve cells—it’s practically a brain unto itself. And indeed, the gut actually talks to the brain, releasing hormones into the bloodstream that, over the course of about 10 minutes, tell us how hungry it is, or that we shouldn’t have eaten an entire pizza. But a new study reveals the gut has a much more direct connection to the brain through a neural circuit that allows it to transmit signals in mere seconds. The findings could lead to new treatments for obesity, eating disorders, and even depression and autism—all of which have been linked to a malfunctioning gut. The study reveals “a new set of pathways that use gut cells to rapidly communicate with … the brain stem,” says Daniel Drucker, a clinician-scientist who studies gut disorders at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, who was not involved with the work. Although many questions remain before the clinical implications become clear, he says, “This is a cool new piece of the puzzle.” Spike Lee

Spike Lee Stephen Hawking sadly

Stephen Hawking sadly