Bernard E. Harcourt in The Ideas Letter:

In a blizzard of executive orders and emergency declarations, President Donald Trump has taken a hatchet to the American government and the global order. He is wrecking the administrative state, shuttering entire agencies and departments, laying off federal workers, firing inspectors general. He is deporting permanent residents for speech protected by the First Amendment, revoking visas from international students, sending immigrants to the military camp at Guantánamo Bay and a mega-prison in El Salvador, and trying to eliminate birthright citizenship. He is defunding research universities and attacking the legal profession. He is threatening draconian tariffs on the country’s closest allies and neighbors, demeaning their leaders, and pulling the United States out of longstanding international commitments. Every day, he launches another unprecedented offensive or changes course; he creates ambiguity and fuels confusion, leaving his critics to second-guess themselves while giving himself cover.

He remains extremely popular with his base, even if his overall ratings have dropped to record lows. His critics, though, attack him six ways from Sunday. They call him a fascist, an authoritarian, a tyrant, the kleptocratic tool of tech billionaires, a profiteer, a reality-TV impostor, the embodiment of toxic masculinity, a bully. Yet none of these labels fully captures the scope or the coherence of what is happening in the U.S. today. These diagnoses focus too much on the individual, and this is an individual who, like a virtuoso illusionist, keeps his audience mesmerized by the spectacle but distracted from what is really going on. The radical developments underway must be placed in deeper perspective.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery.

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery. For hard as it still may be to believe, let alone process, in barely one hundred days we have already fallen into a form of governance in which legally resident individuals (currently by and large immigrants of one sort or another—mothers, fathers, students with entirely current green cards or asylum claims—but with every indication that such tactics will presently be getting extended to full-fledged citizens as well) are literally being spirited off the streets by masked men in unmarked cars and, without the slightest due process or the most tenuous access to any sort of recourse, whisked off to prisons, both at home and abroad, seemingly beyond the sanction of any sort of judicial oversight (the rulings of judges flagrantly ignored and the judges themselves now starting to get subjected to arbitrary arrest as well simply for even having expressed them), the legislative branch cowed into impotence by the abject servitude of its barely majority party, the executive branch a whipsaw of whims and tantrums, with no end in sight.

For hard as it still may be to believe, let alone process, in barely one hundred days we have already fallen into a form of governance in which legally resident individuals (currently by and large immigrants of one sort or another—mothers, fathers, students with entirely current green cards or asylum claims—but with every indication that such tactics will presently be getting extended to full-fledged citizens as well) are literally being spirited off the streets by masked men in unmarked cars and, without the slightest due process or the most tenuous access to any sort of recourse, whisked off to prisons, both at home and abroad, seemingly beyond the sanction of any sort of judicial oversight (the rulings of judges flagrantly ignored and the judges themselves now starting to get subjected to arbitrary arrest as well simply for even having expressed them), the legislative branch cowed into impotence by the abject servitude of its barely majority party, the executive branch a whipsaw of whims and tantrums, with no end in sight. The lead singer and primary lyricist of the long-running rock band U2, Bono has never exactly been the shy type. Outside of Elvis posing with Nixon, no rock star has seemed so comfortable posing with so many politicians, and Bono has perhaps set the record for the most Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame induction speeches given.3 A preacherly ambition propels Bono’s memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, as the book chronicles U2’s forty-odd-year career, and the book’s impact hinges on your openness to Bono’s expansiveness. While no fruit is thrown at rock royalty, Surrender as a whole offers a smart and charmingly self-deprecating portrait of Bono and his three friends from Dublin as they propel themselves from scruffy post-punk band to one of the last of the great rock ’n’ roll acts, one of the few bands from their era that can stand with the Stones and the McCartneys in the cavernous sports arenas around the world. If a talking head is needed to wax poetic on America, rock ’n’ roll, debt relief, religion, sex, life, death—I am sure he has an opinion on cross-stitching—Bono is the person to turn to.

The lead singer and primary lyricist of the long-running rock band U2, Bono has never exactly been the shy type. Outside of Elvis posing with Nixon, no rock star has seemed so comfortable posing with so many politicians, and Bono has perhaps set the record for the most Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame induction speeches given.3 A preacherly ambition propels Bono’s memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, as the book chronicles U2’s forty-odd-year career, and the book’s impact hinges on your openness to Bono’s expansiveness. While no fruit is thrown at rock royalty, Surrender as a whole offers a smart and charmingly self-deprecating portrait of Bono and his three friends from Dublin as they propel themselves from scruffy post-punk band to one of the last of the great rock ’n’ roll acts, one of the few bands from their era that can stand with the Stones and the McCartneys in the cavernous sports arenas around the world. If a talking head is needed to wax poetic on America, rock ’n’ roll, debt relief, religion, sex, life, death—I am sure he has an opinion on cross-stitching—Bono is the person to turn to. For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of

For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of  I have deep affection for the people of both India and Pakistan, and am dismayed by what I see as a looming train wreck on the Indus, with disastrous consequences for both countries. I will outline why there is no objective conflict of interests between the countries over the waters of the Indus Basin, make some observations of the need for a change in public discourse, and suggest how the drivers of the train can put on the brakes before it is too late.

I have deep affection for the people of both India and Pakistan, and am dismayed by what I see as a looming train wreck on the Indus, with disastrous consequences for both countries. I will outline why there is no objective conflict of interests between the countries over the waters of the Indus Basin, make some observations of the need for a change in public discourse, and suggest how the drivers of the train can put on the brakes before it is too late. A few years ago

A few years ago It is almost certainly the most consequential 100 days that scientists in the United States have experienced since the end of World War II.

It is almost certainly the most consequential 100 days that scientists in the United States have experienced since the end of World War II. On October 6, 1973, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was ordered by prison guards to run double-time across Buru Island. The writer had been arrested eight years before, taken into custody in the middle of the night. Detained without charges alongside thousands of other men and women, Toer was sent to Buru—a prison island far east of Java and Bali—and forced to toil under the scorching sun. He was desolate, not only because of the Sisyphean labor he was made to perform, the inability to write, and the gnawing feeling of injustice, but also because he was separated from his family. Before prison, he had been happily married to his beloved Maimoenah, his second wife and mother to five of his children. After several years of seclusion from the outside world, Toer was hopeful that the press junket he was being forced to attend could be an opportunity to petition for the freedoms that had been revoked when he was imprisoned, if not ensure his release. It would be the closest he would get to a trial, during which he could publicly question the validity of his arrest.

On October 6, 1973, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was ordered by prison guards to run double-time across Buru Island. The writer had been arrested eight years before, taken into custody in the middle of the night. Detained without charges alongside thousands of other men and women, Toer was sent to Buru—a prison island far east of Java and Bali—and forced to toil under the scorching sun. He was desolate, not only because of the Sisyphean labor he was made to perform, the inability to write, and the gnawing feeling of injustice, but also because he was separated from his family. Before prison, he had been happily married to his beloved Maimoenah, his second wife and mother to five of his children. After several years of seclusion from the outside world, Toer was hopeful that the press junket he was being forced to attend could be an opportunity to petition for the freedoms that had been revoked when he was imprisoned, if not ensure his release. It would be the closest he would get to a trial, during which he could publicly question the validity of his arrest. A

A At its heart, cricket stands as a wonderfully pastoral exercise in deferred gratification. Today, there are various forms of the sport around the world, but to most purists its true and highest expression lies in the international, or “test,” match, involving, say, England playing Australia or India facing Pakistan. Such encounters typically last five full days, with roughly eight hours of actual sport each day and the contestants communally decamping to a hotel each evening and returning to pick up where they left off the following morning. Twice a day, the same players leave the field and stroll back to the pavilion, or clubhouse, for a good meal, and on the warmer afternoons—rarely an issue during matches in England—a uniformed attendant will periodically appear on the field bearing a tray of assorted refreshments. Just to give you a sense of the essentially unhurried nature of the enterprise, a single batter can remain at his post for several hours, if not entire days, on end, and, if sufficiently skillful, accrue upwards of one hundred individual runs before being dismissed. In another of cricket’s cherished rituals, he can expect to be warmly applauded by his opponents on reaching such a milestone.

At its heart, cricket stands as a wonderfully pastoral exercise in deferred gratification. Today, there are various forms of the sport around the world, but to most purists its true and highest expression lies in the international, or “test,” match, involving, say, England playing Australia or India facing Pakistan. Such encounters typically last five full days, with roughly eight hours of actual sport each day and the contestants communally decamping to a hotel each evening and returning to pick up where they left off the following morning. Twice a day, the same players leave the field and stroll back to the pavilion, or clubhouse, for a good meal, and on the warmer afternoons—rarely an issue during matches in England—a uniformed attendant will periodically appear on the field bearing a tray of assorted refreshments. Just to give you a sense of the essentially unhurried nature of the enterprise, a single batter can remain at his post for several hours, if not entire days, on end, and, if sufficiently skillful, accrue upwards of one hundred individual runs before being dismissed. In another of cricket’s cherished rituals, he can expect to be warmly applauded by his opponents on reaching such a milestone. Yu, now an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), is a leader in a field known as “physics-guided deep learning,” having spent years incorporating our knowledge of physics into artificial neural networks. The work has not only introduced novel techniques for building and training these systems, but it’s also allowed her to make progress on several real-world applications. She has drawn on principles of fluid dynamics to improve traffic predictions, sped up simulations of turbulence to enhance our understanding of hurricanes and devised tools that helped predict the spread of Covid-19.

Yu, now an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), is a leader in a field known as “physics-guided deep learning,” having spent years incorporating our knowledge of physics into artificial neural networks. The work has not only introduced novel techniques for building and training these systems, but it’s also allowed her to make progress on several real-world applications. She has drawn on principles of fluid dynamics to improve traffic predictions, sped up simulations of turbulence to enhance our understanding of hurricanes and devised tools that helped predict the spread of Covid-19. One of the most interesting films on Netflix is

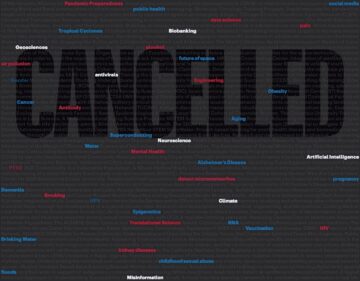

One of the most interesting films on Netflix is  In just the first three months of his second term, US President Donald Trump has destabilized eight decades of government support for science. His administration has fired thousands of government scientists, bringing large swathes of the country’s research to a standstill and halting many clinical trials. It has threatened to

In just the first three months of his second term, US President Donald Trump has destabilized eight decades of government support for science. His administration has fired thousands of government scientists, bringing large swathes of the country’s research to a standstill and halting many clinical trials. It has threatened to