Matt Wray at Public Books:

So, again, why is there no socialism in the United States? Perhaps when the millennial generation comes to power, the question will no longer make much sense. But if these enthusiastic young fans of socialist democracy are ever to win big in American electoral politics, it’s going to be because they will have figured out a new way to talk about class in America. And to do that, they will need to understand some of the different ways that Americans have thought—and felt—about class. And to do that, they might want to read a neglected classic of American sociology—The American Perception of Class, by Reeve Vanneman and Lynn Cannon, just reissued as an open access title by Temple University Press and available for free download here.1 The book is a classic example of how to use sociological reasoning and methods to debunk widely held myths. In this case, the myths were about the lack of class consciousness in America, myths that can be traced back to Sombart.

So, again, why is there no socialism in the United States? Perhaps when the millennial generation comes to power, the question will no longer make much sense. But if these enthusiastic young fans of socialist democracy are ever to win big in American electoral politics, it’s going to be because they will have figured out a new way to talk about class in America. And to do that, they will need to understand some of the different ways that Americans have thought—and felt—about class. And to do that, they might want to read a neglected classic of American sociology—The American Perception of Class, by Reeve Vanneman and Lynn Cannon, just reissued as an open access title by Temple University Press and available for free download here.1 The book is a classic example of how to use sociological reasoning and methods to debunk widely held myths. In this case, the myths were about the lack of class consciousness in America, myths that can be traced back to Sombart.

more here.

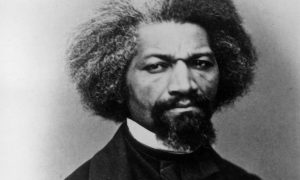

“Douglass engaged in a lifelong autobiographical quest for a coherent story of ascendance and familial identity,” Blight writes, and “for the healing of his own wounds”. Douglass himself thundered that slavery “converted the mother that bore me into a myth, it shrouded my father in mystery, and left me without an intelligible beginning in the world”. He yearned for “a bright gleam of a mother’s love”.

“Douglass engaged in a lifelong autobiographical quest for a coherent story of ascendance and familial identity,” Blight writes, and “for the healing of his own wounds”. Douglass himself thundered that slavery “converted the mother that bore me into a myth, it shrouded my father in mystery, and left me without an intelligible beginning in the world”. He yearned for “a bright gleam of a mother’s love”. Imaginary Lives (1896) was Schwob’s last book of fiction. He composed its twenty-two chapters—each one the story of a life, recounted in fewer than a dozen pages, with all of these lives arranged in chronological order—between 1893 and 1896. Early in its composition, at the age of twenty-six, Schwob suffered the first attack of a mysterious intestinal ailment whose painful effects and questionable treatments (ether, opium, morphine) would lead to his death at thirty-seven. Schwob’s physical condition to some extent shaped his fiction, and though all the chapters of Imaginary Lives culminate, naturally enough, in their subjects’ deaths, these deaths are often unnaturally violent. Lucretius the Poet is poisoned by his lover. Clodia the Licentious Matron is strangled, robbed, and dumped in the river Tiber. Gabriel Spenser the Actor is stabbed in the lung by Ben Jonson the playwright. And the three pirates of the book (Captain Kidd, Walter Kennedy, Stede Bonnet) are hanged and left to rot upon the rope. Imaginary Lives is, among other things, a study of human violence, proceeding from the sun-stroked era of ancient Greek gods and demigods to the soot-blackened nineteenth-century Edinburgh of the serial murderers Burke and Hare.

Imaginary Lives (1896) was Schwob’s last book of fiction. He composed its twenty-two chapters—each one the story of a life, recounted in fewer than a dozen pages, with all of these lives arranged in chronological order—between 1893 and 1896. Early in its composition, at the age of twenty-six, Schwob suffered the first attack of a mysterious intestinal ailment whose painful effects and questionable treatments (ether, opium, morphine) would lead to his death at thirty-seven. Schwob’s physical condition to some extent shaped his fiction, and though all the chapters of Imaginary Lives culminate, naturally enough, in their subjects’ deaths, these deaths are often unnaturally violent. Lucretius the Poet is poisoned by his lover. Clodia the Licentious Matron is strangled, robbed, and dumped in the river Tiber. Gabriel Spenser the Actor is stabbed in the lung by Ben Jonson the playwright. And the three pirates of the book (Captain Kidd, Walter Kennedy, Stede Bonnet) are hanged and left to rot upon the rope. Imaginary Lives is, among other things, a study of human violence, proceeding from the sun-stroked era of ancient Greek gods and demigods to the soot-blackened nineteenth-century Edinburgh of the serial murderers Burke and Hare. This year has been exhausting in so many ways, asking us to accept more than it seems we can, more than it seems should be possible. But really, in the end, today’s harsh realities are not all that surprising for some of us — for people of color, or for people from marginalized communities — who have long since given up on being shocked or dismayed by the news, by what this or that administration will allow, what this or that police department will excuse, who will be exonerated, what this or that fellow American is willing to let be, either by contribution or complicity. All this is done in the name of white supremacy under the guise of patriotism and conservatism, to keep things as they are, favoring white people over every other citizen, because where’s the incentive to give up privilege if you have it? Now more than ever I believe fiction can change minds, build empathy by asking readers to walk in others’ shoes, and thereby contribute to real change. In “Friday Black,” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now, at the end of this year, as we inch ever closer to what feels like an inevitable phenomenal catastrophe or some other kind of radical change, for better or for worse. And when you can’t believe what’s happening in reality, there is no better time to suspend your disbelief and read and trust in a work of fiction — in what it can do.

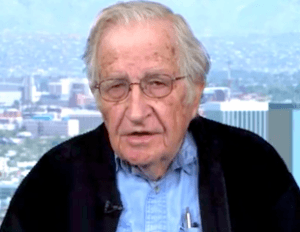

This year has been exhausting in so many ways, asking us to accept more than it seems we can, more than it seems should be possible. But really, in the end, today’s harsh realities are not all that surprising for some of us — for people of color, or for people from marginalized communities — who have long since given up on being shocked or dismayed by the news, by what this or that administration will allow, what this or that police department will excuse, who will be exonerated, what this or that fellow American is willing to let be, either by contribution or complicity. All this is done in the name of white supremacy under the guise of patriotism and conservatism, to keep things as they are, favoring white people over every other citizen, because where’s the incentive to give up privilege if you have it? Now more than ever I believe fiction can change minds, build empathy by asking readers to walk in others’ shoes, and thereby contribute to real change. In “Friday Black,” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now, at the end of this year, as we inch ever closer to what feels like an inevitable phenomenal catastrophe or some other kind of radical change, for better or for worse. And when you can’t believe what’s happening in reality, there is no better time to suspend your disbelief and read and trust in a work of fiction — in what it can do. Linguist and long-time political gadfly Noam Chomsky argued in an interview Friday that President Donald Trump’s poisonous and violent rhetoric fueling hatred in the United States has a deep lineage in the country — and also accentuates the country’s role in an “alliance of reactionary and repressive states” worldwide. Asked by Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman to reflect on the recent

Linguist and long-time political gadfly Noam Chomsky argued in an interview Friday that President Donald Trump’s poisonous and violent rhetoric fueling hatred in the United States has a deep lineage in the country — and also accentuates the country’s role in an “alliance of reactionary and repressive states” worldwide. Asked by Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman to reflect on the recent  In her New York Times op-ed “

In her New York Times op-ed “

Aasia bibi

Aasia bibi In his 1927 essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” the influential horror writer H.P. Lovecraft declares that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” The contemporary Swedish poet

In his 1927 essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” the influential horror writer H.P. Lovecraft declares that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” The contemporary Swedish poet

I will

I will How democratic is the United States? According to a

How democratic is the United States? According to a  You are what you eat. The atoms in your body come from the food and drink you consume – and, to some extent, from the air you breathe. That is not terribly surprising. What few people realise, however, is that about half the nitrogen atoms in your body have passed through something called a Haber-Bosch reaction. This chemical process, invented just before the first world war, did as much to change the

You are what you eat. The atoms in your body come from the food and drink you consume – and, to some extent, from the air you breathe. That is not terribly surprising. What few people realise, however, is that about half the nitrogen atoms in your body have passed through something called a Haber-Bosch reaction. This chemical process, invented just before the first world war, did as much to change the  W

W The

The  I was particularly interested in sexuality and online porn. If, as Stephens-Davidowitz puts it, “Google is a digital truth serum,” then what else does it tell us about our private thoughts and desires? What else are we hiding from our friends, neighbors, and colleagues?

I was particularly interested in sexuality and online porn. If, as Stephens-Davidowitz puts it, “Google is a digital truth serum,” then what else does it tell us about our private thoughts and desires? What else are we hiding from our friends, neighbors, and colleagues? T

T