Iwan Morus in Independent:

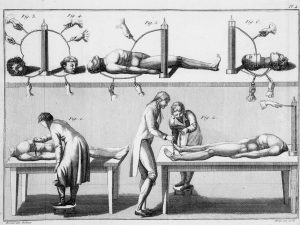

On 17 January 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified. The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “animal electricity” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Timesnewspaper reported: “On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.”

On 17 January 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified. The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “animal electricity” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Timesnewspaper reported: “On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.”

It looked to some spectators “as if the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life”.

…The idea that electricity really was the stuff of life and that it might be used to bring back the dead was certainly a familiar one in the kinds of circles in which the young Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley – the author of Frankenstein – moved. The English poet, and family friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was fascinated by the connections between electricity and life. Writing to his friend the chemist Humphry Davy after hearing that he was giving lectures at the Royal Institution in London, he told him how his “motive muscles tingled and contracted at the news, as if you had bared them and were zincifying the life-mocking fibres”. Percy Bysshe Shelley himself – who would become Wollstonecraft’s husband in 1816 – was another enthusiast for galvanic experimentation.

More here.

He scanned my medical history, and the answer was there in black and white: a body mass index of 24, blood pressure a shade lower than the normal range, total cholesterol below 120, and no chronic disorders or ailments to speak of. There was just one outlier in this picture of good health: I recently turned 67. Which is why, when I saw a new doctor for my annual checkup, he had a hard time believing I wasn’t taking an arsenal of drugs simply to remain upright. There is plenty of alarm about the unprecedented aging of humanity. Since 1950, the median age in developed countries has jumped from 28 to 40, and is expected to reach 44 by mid-century. The percentage of citizens age 65 and older is expanding accordingly, from less than 10 percent in 1950 in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan to a respective 20, 30, and 40 percent by 2050. The fear is that, as baby boomers like me march lockstep into “retirement age” (the first of us crested that hill in 2011), there will be fewer young workers to support us old folk, which will curb spending, strain the healthcare system, and drain Social Security and Medicare benefits.

He scanned my medical history, and the answer was there in black and white: a body mass index of 24, blood pressure a shade lower than the normal range, total cholesterol below 120, and no chronic disorders or ailments to speak of. There was just one outlier in this picture of good health: I recently turned 67. Which is why, when I saw a new doctor for my annual checkup, he had a hard time believing I wasn’t taking an arsenal of drugs simply to remain upright. There is plenty of alarm about the unprecedented aging of humanity. Since 1950, the median age in developed countries has jumped from 28 to 40, and is expected to reach 44 by mid-century. The percentage of citizens age 65 and older is expanding accordingly, from less than 10 percent in 1950 in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan to a respective 20, 30, and 40 percent by 2050. The fear is that, as baby boomers like me march lockstep into “retirement age” (the first of us crested that hill in 2011), there will be fewer young workers to support us old folk, which will curb spending, strain the healthcare system, and drain Social Security and Medicare benefits. Can we, after all these months, find it within ourselves to manage a teeny-tiny, eensie-weensie, little itty-bitty smidgen of sympathy for Donald Trump? It doesn’t have to be much. Something about the size of the period at the end of this sentence would do. I mean, all the man did was run for president and accidentally win, and now it’s all over Twitter and everywhere else that he could end up in jail! C’mon folks, just look at the guy. It all started out so innocently back in the summer of 2015. He started out the only way he knew how: by running a reality TV show of a campaign. Remember that so-called “rally” in the lobby of Trump Tower when he announced? I mean, he and Melania coming down that escalator like a political Gloria Swanson descending the staircase of her mansion in “Sunset Boulevard.” He may as well have turned to the camera and said, “I’m ready for my close-up.” Even the crowd was mostly extras hired from an open casting call.

Can we, after all these months, find it within ourselves to manage a teeny-tiny, eensie-weensie, little itty-bitty smidgen of sympathy for Donald Trump? It doesn’t have to be much. Something about the size of the period at the end of this sentence would do. I mean, all the man did was run for president and accidentally win, and now it’s all over Twitter and everywhere else that he could end up in jail! C’mon folks, just look at the guy. It all started out so innocently back in the summer of 2015. He started out the only way he knew how: by running a reality TV show of a campaign. Remember that so-called “rally” in the lobby of Trump Tower when he announced? I mean, he and Melania coming down that escalator like a political Gloria Swanson descending the staircase of her mansion in “Sunset Boulevard.” He may as well have turned to the camera and said, “I’m ready for my close-up.” Even the crowd was mostly extras hired from an open casting call. I. GARY SNYDER SAID that we know our minds are wild because of the difficulty of making ourselves think what we think we ought to think.

I. GARY SNYDER SAID that we know our minds are wild because of the difficulty of making ourselves think what we think we ought to think. ‘I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection.

‘I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection. David Duvenaud was collaborating on a project involving medical data when he ran up against a major shortcoming in AI.

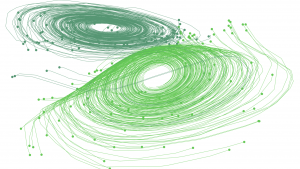

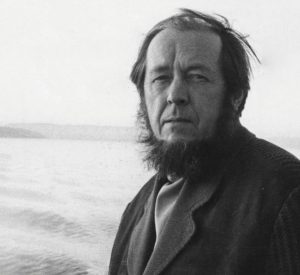

David Duvenaud was collaborating on a project involving medical data when he ran up against a major shortcoming in AI. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, pundits offered a variety of reasons for its failure: economic, political, military. Few thought to add a fourth, more elusive cause: the regime’s total loss of credibility.

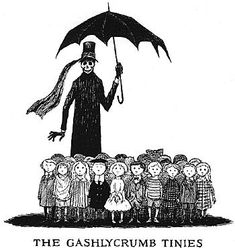

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, pundits offered a variety of reasons for its failure: economic, political, military. Few thought to add a fourth, more elusive cause: the regime’s total loss of credibility. Gorey has here and there been described as ‘Dr Seuss for Tim Burton fans’ and ‘the Charles Schulz of the macabre’, but he was in every way more wayward and interesting than that. He wrote almost impossible to classify little books — crunched-down Victorian novels — that seemed to belong in the children’s sections of bookshops but were quite unsuited to children, in whom he took little or no interest. He found a public only very slowly, and over many years — thanks, in large part, to till-point placement and Hello-Kitty-scale merchandising efforts by the Gotham Book Mart in New York.

Gorey has here and there been described as ‘Dr Seuss for Tim Burton fans’ and ‘the Charles Schulz of the macabre’, but he was in every way more wayward and interesting than that. He wrote almost impossible to classify little books — crunched-down Victorian novels — that seemed to belong in the children’s sections of bookshops but were quite unsuited to children, in whom he took little or no interest. He found a public only very slowly, and over many years — thanks, in large part, to till-point placement and Hello-Kitty-scale merchandising efforts by the Gotham Book Mart in New York. E

E

Minutes before stepping out into the spotlight on a stage – totally naked – I am wondering whether to wear socks. “It’s cold,” shivers another performer. A friend counsels, “If you’re going out naked, do it in full.” The matter of the sock is a distraction from the fact that we’re about to show our willies to the masses. This might not be Wembley Arena, but the trendy basement bar in east London I’m performing in is packed with people – mainly men. Anticipation crackles among them. They giggle about picking seats with a good view of the stage. There are twice as many eyeballs as people. And each one of them is about to see all I have.

Minutes before stepping out into the spotlight on a stage – totally naked – I am wondering whether to wear socks. “It’s cold,” shivers another performer. A friend counsels, “If you’re going out naked, do it in full.” The matter of the sock is a distraction from the fact that we’re about to show our willies to the masses. This might not be Wembley Arena, but the trendy basement bar in east London I’m performing in is packed with people – mainly men. Anticipation crackles among them. They giggle about picking seats with a good view of the stage. There are twice as many eyeballs as people. And each one of them is about to see all I have. Brain conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder have long been known to have an inherited component, but pinpointing

Brain conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder have long been known to have an inherited component, but pinpointing

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat.

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat. We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact.

We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact.