Sarah Baxter in Literary Hub:

The pub is warm and beery. Grog glasses—drained, foam stained—scatter sticky veneer. Red-wine lips, hoppy breath, a slurry of slurring; laughter like gunfire, craic-ing off the wood panels, mirror walls and ranks of whiskey bottles. Bar talk is of theology and adultery, literature and death, soap and sausages. Everything and nothing, discussed or daydreamed over a quick cheese sandwich. A nothing old day. But the stuff of life—infinitesimal yet essential—all the same . . .

The pub is warm and beery. Grog glasses—drained, foam stained—scatter sticky veneer. Red-wine lips, hoppy breath, a slurry of slurring; laughter like gunfire, craic-ing off the wood panels, mirror walls and ranks of whiskey bottles. Bar talk is of theology and adultery, literature and death, soap and sausages. Everything and nothing, discussed or daydreamed over a quick cheese sandwich. A nothing old day. But the stuff of life—infinitesimal yet essential—all the same . . .

James Joyce’s Ulysses—variously considered the most momentous, accomplished, infuriating and unreadable book in the English language—is the ordinary made extraordinary. It’s a modernist reworking of Homer’s Odyssey, but while the Ancient Greek poem tells of Odysseus’ incident-packed return from the Trojan War, Joyce makes an epic out of a single, unremarkable day.

Ulysses follows Leopold Bloom, a Jewish ad canvasser for The Freeman’s Journal, as he wanders around Dublin on June 16, 1904. He attends a funeral, goes to the pub, ducks into a museum (to avoid the man sleeping with his wife), pleasures himself by Sandymount Strand, enters the red-light district. The novel is a chaotic stream of consciousness, performing stylistic acrobatics to try to render the human experience. But it is grounded in the streets of Dublin. Joyce, writing from self-exile in Paris, slavishly researched the physicality of the city. Though he seldom returned, he remained tethered: “When I die,” he once said, “Dublin will be written in my heart.”

More here.

One of the key misconceptions about solar geoengineering — putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and reduce global warming — is that it could be used as a fix-all to reverse global warming trends and bring temperature back to pre-industrial levels.

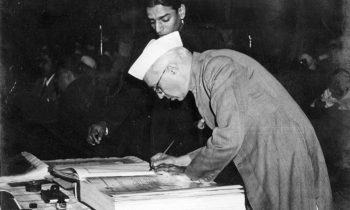

One of the key misconceptions about solar geoengineering — putting aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and reduce global warming — is that it could be used as a fix-all to reverse global warming trends and bring temperature back to pre-industrial levels. The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their ‘constitutional rights’ – especially the ‘fundamental right’ of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution. In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit ‘direct rule by the centre’, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of ‘supremacy’ over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are ‘undemocratic’ in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants.

The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their ‘constitutional rights’ – especially the ‘fundamental right’ of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution. In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit ‘direct rule by the centre’, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of ‘supremacy’ over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are ‘undemocratic’ in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants. T

T Homeland is essentially a road trip novel, but its road trip doesn’t work. Contra to the willful American model of making off into the great vistas of the West, Jonathan and his feckless companions (a racing driver and a sexist caricature of a press officer, Frau Winkelvoss) can’t escape the traumas of East Prussia’s landscape. To paraphrase Joan Didion, history has very much bloodied the land here, leaving it irrevocably besmirched and hard to navigate (as the aptly titled Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder can attest). Instead of experiencing the desired transcendental realization while standing on the Vistula Spit, Jonathan thinks about the “chests of drawers and grandfather clocks” on wagons making their way across the Wisła while under fire from British bombers and Red Army tanks, and that when the ferries crammed with refugees sank, and the dishes in their mahogany dining rooms slid to the floor, “no-one sang hymns.” The final pages of the novel see him scooping some sand from the presumed spot of his father’s death into a medicine bottle, with the vague hope that a forensic lab will be able to analyze it for DNA — a final bathetic pun on the notion of the German fatherland.

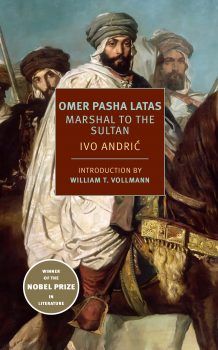

Homeland is essentially a road trip novel, but its road trip doesn’t work. Contra to the willful American model of making off into the great vistas of the West, Jonathan and his feckless companions (a racing driver and a sexist caricature of a press officer, Frau Winkelvoss) can’t escape the traumas of East Prussia’s landscape. To paraphrase Joan Didion, history has very much bloodied the land here, leaving it irrevocably besmirched and hard to navigate (as the aptly titled Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder can attest). Instead of experiencing the desired transcendental realization while standing on the Vistula Spit, Jonathan thinks about the “chests of drawers and grandfather clocks” on wagons making their way across the Wisła while under fire from British bombers and Red Army tanks, and that when the ferries crammed with refugees sank, and the dishes in their mahogany dining rooms slid to the floor, “no-one sang hymns.” The final pages of the novel see him scooping some sand from the presumed spot of his father’s death into a medicine bottle, with the vague hope that a forensic lab will be able to analyze it for DNA — a final bathetic pun on the notion of the German fatherland. Andrić is particularly remarkable for his psychological acuity. Consider the knot of complexity that is Omer Pasha: born Mićo Latas, he’d been a brilliant boy in a village too small to contain his ambitions. He was bored by his parents and the provincial people around him. He managed to acquire a scholarship to military school—Austrian, not Turkish—but, just as he is ready to graduate, he receives word that his father, a minor officer, “a weak man…a small, overlooked man,” has been indicted for misuse of state funds. The stigma will prevent Mićo from achieving any career at all. This is when he takes off for Istanbul to scrape together an entirely new life.

Andrić is particularly remarkable for his psychological acuity. Consider the knot of complexity that is Omer Pasha: born Mićo Latas, he’d been a brilliant boy in a village too small to contain his ambitions. He was bored by his parents and the provincial people around him. He managed to acquire a scholarship to military school—Austrian, not Turkish—but, just as he is ready to graduate, he receives word that his father, a minor officer, “a weak man…a small, overlooked man,” has been indicted for misuse of state funds. The stigma will prevent Mićo from achieving any career at all. This is when he takes off for Istanbul to scrape together an entirely new life. The New Zealand killer takes his place in the cracked pantheon of violent, Trump-admiring extremists: beside the gunman at the Tree of Life synagogue, in Pittsburgh, who blamed Jews for resettling refugees and immigrants, whom Trump vilifies as the center of his politics; beside the van-dweller in Miami who found purpose amid the throngs of Trump rallies and set about sending pipe bombs to George Soros, journalists, and Democrats. The New Zealand killer did not exact his violence in America, but

The New Zealand killer takes his place in the cracked pantheon of violent, Trump-admiring extremists: beside the gunman at the Tree of Life synagogue, in Pittsburgh, who blamed Jews for resettling refugees and immigrants, whom Trump vilifies as the center of his politics; beside the van-dweller in Miami who found purpose amid the throngs of Trump rallies and set about sending pipe bombs to George Soros, journalists, and Democrats. The New Zealand killer did not exact his violence in America, but  Maybe because we’re living in a dystopia, it feels as if we’ve become obsessed with prophecy of late. Protest signs at the 2017 Women’s March read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” and “Octavia Warned Us.” News headlines about abortion bans and the defunding of Planned Parenthood do seem ripped from the pages of Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985). And Octavia Butler’s “Parable” series, published in the 1990s, did eerily feature a presidential candidate who vows to “make America great again.”

Maybe because we’re living in a dystopia, it feels as if we’ve become obsessed with prophecy of late. Protest signs at the 2017 Women’s March read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” and “Octavia Warned Us.” News headlines about abortion bans and the defunding of Planned Parenthood do seem ripped from the pages of Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985). And Octavia Butler’s “Parable” series, published in the 1990s, did eerily feature a presidential candidate who vows to “make America great again.” To be sure, the bipartisan civic ethos is an indispensable ingredient of a flourishing democracy. But it cannot be cultivated under conditions where everything we do is plausibly regarded an expression of our political loyalties. When politics is all we ever do together, our efforts to repair democracy by means of strategies for enacting better politics are doomed simply to backfire. What is required instead is the reclaiming of regions of social space for shared activities that are in no way political, occasions for cooperative endeavors in which the participants’ political affiliations are not merely suppressed or bracketed, but irrelevant and out of place. If you now find yourself wondering whether such collaborations could possibly exist, you have placed your finger firmly on the problem of polarization. For polarization has led not only to the colonization of our social environments by politics, it also has enabled politics to seize and confine our social imagination. That we must struggle to conceptualize avenues of social collaboration that are not structured around our political identities is the fullest manifestation of the problem of polarization. To frame the upshot somewhat paradoxically, if we want to repair our democracy, we need to focus our collective attention elsewhere.

To be sure, the bipartisan civic ethos is an indispensable ingredient of a flourishing democracy. But it cannot be cultivated under conditions where everything we do is plausibly regarded an expression of our political loyalties. When politics is all we ever do together, our efforts to repair democracy by means of strategies for enacting better politics are doomed simply to backfire. What is required instead is the reclaiming of regions of social space for shared activities that are in no way political, occasions for cooperative endeavors in which the participants’ political affiliations are not merely suppressed or bracketed, but irrelevant and out of place. If you now find yourself wondering whether such collaborations could possibly exist, you have placed your finger firmly on the problem of polarization. For polarization has led not only to the colonization of our social environments by politics, it also has enabled politics to seize and confine our social imagination. That we must struggle to conceptualize avenues of social collaboration that are not structured around our political identities is the fullest manifestation of the problem of polarization. To frame the upshot somewhat paradoxically, if we want to repair our democracy, we need to focus our collective attention elsewhere.

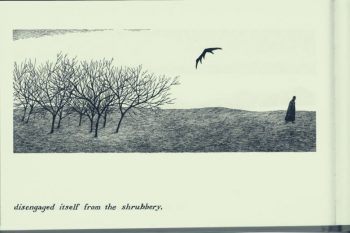

With its somewhat whimsical skulls and bats, Gorey’s more accessible work has all the trimmings of Gothic Lite, part of the same cultural wave that has made H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu into a popular plush toy. It tends to be set in a waveringly Victorian-Edwardian fin-de-siècle, or a louche and sometimes sinister vision of the 1920s. As Dery notes, Gorey’s retro negativity is partly “a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present” and its crass positivity (its “Trumpian vulgarity”, as Dery calls it). Gorey’s friend Alison Lurie sees his fascination with funereal Victorianism as a reaction to the 1950s ethos according to which “everything was wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining”; and the Washington Post writer Henry Allen described him, in an obituary appreciation, as having “reached deeper into the educated American psyche” than Charles Addams, with whom he was sometimes paired: for Allen, he defied “the clamorous Doris Day optimism rampant at the start of his career”. Another of Gorey’s sharpest commentators, Thomas Garvey, writing in a context of Queer Theory, has suggested that Gorey’s ironic perversity “allows his art to be re-purposed by heterosexuals into a tonic for the pressures of wholesomeness”.

With its somewhat whimsical skulls and bats, Gorey’s more accessible work has all the trimmings of Gothic Lite, part of the same cultural wave that has made H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu into a popular plush toy. It tends to be set in a waveringly Victorian-Edwardian fin-de-siècle, or a louche and sometimes sinister vision of the 1920s. As Dery notes, Gorey’s retro negativity is partly “a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present” and its crass positivity (its “Trumpian vulgarity”, as Dery calls it). Gorey’s friend Alison Lurie sees his fascination with funereal Victorianism as a reaction to the 1950s ethos according to which “everything was wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining”; and the Washington Post writer Henry Allen described him, in an obituary appreciation, as having “reached deeper into the educated American psyche” than Charles Addams, with whom he was sometimes paired: for Allen, he defied “the clamorous Doris Day optimism rampant at the start of his career”. Another of Gorey’s sharpest commentators, Thomas Garvey, writing in a context of Queer Theory, has suggested that Gorey’s ironic perversity “allows his art to be re-purposed by heterosexuals into a tonic for the pressures of wholesomeness”. In June, 2015, Roberto Carlos Lange, who records as Helado Negro, released a single titled “Young, Latin and Proud.” Despite the bold title, the song sounded more like a flicker than like a flame. It was tranquil and soothing, with Lange singing gently, almost timidly, over a swaying synth line. His lyrics were addressed to a younger version of himself—someone searching for the language to make sense of his own story: “And you can only view you / With what you got / You don’t have to pretend / That you got to know more / ’Cause you are young, Latin, and proud.”

In June, 2015, Roberto Carlos Lange, who records as Helado Negro, released a single titled “Young, Latin and Proud.” Despite the bold title, the song sounded more like a flicker than like a flame. It was tranquil and soothing, with Lange singing gently, almost timidly, over a swaying synth line. His lyrics were addressed to a younger version of himself—someone searching for the language to make sense of his own story: “And you can only view you / With what you got / You don’t have to pretend / That you got to know more / ’Cause you are young, Latin, and proud.” Sex is Johnson’s true subject. She respects its power and repeatedly enacts a woman’s right to sexual realisation. Physical contact is something so fraught and regulated as to be inherently violent. Violence can come out of detachment too: ‘He dragged at the vee of her dress and put his fingers to her breasts.’ Elsie is intent on discovering the facts of life and perturbed by ‘the knitting of her flesh’ when she passes a couple kissing under a tree. When she acquires a boyfriend, Roly, he says he’ll take her clothes off and thrash her if she looks at someone else. Elsie counters that she’d rather like that before realising she has ‘said something very wrong’. She lies down with him but resists. On the way home Roly stops off to see Mrs Maginnis. He orders Nietzsche and Freud in the local library, and arranges a date with the librarian. He blames Elsie’s resistance on the ‘whole social system … When a man loves a woman, he ought to be able to sleep with her right away, and then there would be no repressions or inhibitions.’ When they finally get married and go to bed, ‘there was no fear in her, nor love, only a great loneliness.’

Sex is Johnson’s true subject. She respects its power and repeatedly enacts a woman’s right to sexual realisation. Physical contact is something so fraught and regulated as to be inherently violent. Violence can come out of detachment too: ‘He dragged at the vee of her dress and put his fingers to her breasts.’ Elsie is intent on discovering the facts of life and perturbed by ‘the knitting of her flesh’ when she passes a couple kissing under a tree. When she acquires a boyfriend, Roly, he says he’ll take her clothes off and thrash her if she looks at someone else. Elsie counters that she’d rather like that before realising she has ‘said something very wrong’. She lies down with him but resists. On the way home Roly stops off to see Mrs Maginnis. He orders Nietzsche and Freud in the local library, and arranges a date with the librarian. He blames Elsie’s resistance on the ‘whole social system … When a man loves a woman, he ought to be able to sleep with her right away, and then there would be no repressions or inhibitions.’ When they finally get married and go to bed, ‘there was no fear in her, nor love, only a great loneliness.’ Three Saudi women’s rights activists whose arrests last year have been condemned worldwide are being honored by PEN America. Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain al-Hathloul, and Eman al-Nafjan have won the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, the literary and human rights organization announced Thursday. The award was established in 1987 and is given to writers imprisoned for their work, with previous recipients coming from Ukraine, Egypt and Ethiopia among other countries.

Three Saudi women’s rights activists whose arrests last year have been condemned worldwide are being honored by PEN America. Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain al-Hathloul, and Eman al-Nafjan have won the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, the literary and human rights organization announced Thursday. The award was established in 1987 and is given to writers imprisoned for their work, with previous recipients coming from Ukraine, Egypt and Ethiopia among other countries. We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing — that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to make genetically modified children. By ‘global moratorium’, we do not mean a permanent ban. Rather, we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations, while retaining the right to make their own decisions, voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met. To begin with, there should be a fixed period during which no clinical uses of germline editing whatsoever are allowed. As well as allowing for discussions about the technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical and moral issues that must be considered before germline editing is permitted, this period would provide time to establish an international framework.

We call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing — that is, changing heritable DNA (in sperm, eggs or embryos) to make genetically modified children. By ‘global moratorium’, we do not mean a permanent ban. Rather, we call for the establishment of an international framework in which nations, while retaining the right to make their own decisions, voluntarily commit to not approve any use of clinical germline editing unless certain conditions are met. To begin with, there should be a fixed period during which no clinical uses of germline editing whatsoever are allowed. As well as allowing for discussions about the technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical and moral issues that must be considered before germline editing is permitted, this period would provide time to establish an international framework.