Geoff Ward at The Dublin Review of Books:

So what was it that made Robinson Crusoe different from previous English fiction? First, Defoe was the first major writer in English literature who did not take a plot from mythology, history, legend or prior literature. The next was to be Samuel Richardson (1689-1761) whose immensely important novel Pamela(1740) it will be relevant to mention a little later. In the plots of these two writers we see the difference, for example, from Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. Second, Defoe was the first to convey the reality of time, to portray a life in the bigger picture of a historical process, and in terms of day-to-day thoughts and activities. Although his timings are inconsistent, his narrative convinces us that the action is occurring at a particular time. Third, Defoe was the first to produce a whole narrative as if it took place in a physical environment to which a character was attached by means of vivid detail: the description of objects, for example, such as clothing and implements. Previously and traditionally, place was treated in a vague and generalised way, with only incidental physical description. Fourth, the use of figurative language, previously a prominent feature of romances, was noticeably reduced; it was much rarer in Defoe and Richardson than in any writer before.

So what was it that made Robinson Crusoe different from previous English fiction? First, Defoe was the first major writer in English literature who did not take a plot from mythology, history, legend or prior literature. The next was to be Samuel Richardson (1689-1761) whose immensely important novel Pamela(1740) it will be relevant to mention a little later. In the plots of these two writers we see the difference, for example, from Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. Second, Defoe was the first to convey the reality of time, to portray a life in the bigger picture of a historical process, and in terms of day-to-day thoughts and activities. Although his timings are inconsistent, his narrative convinces us that the action is occurring at a particular time. Third, Defoe was the first to produce a whole narrative as if it took place in a physical environment to which a character was attached by means of vivid detail: the description of objects, for example, such as clothing and implements. Previously and traditionally, place was treated in a vague and generalised way, with only incidental physical description. Fourth, the use of figurative language, previously a prominent feature of romances, was noticeably reduced; it was much rarer in Defoe and Richardson than in any writer before.

more here.

Before I knew who Claire Denis was, she taught me how to dance. When I was eighteen, it was easier to stay in with a movie than to go to a party and be surrounded by strangers. One night, I watched Denis’s film “Beau Travail,” from 1999. Afterward, I couldn’t sleep. I kept replaying the ending, transfixed by a man with a battered face, Galoup. For ninety minutes, Galoup (Denis Lavant) is small and hunched, a military officer who, after being ejected from the French Foreign Legion, can’t find meaning in civilian life. In a closing scene, he makes his bed, carefully tucking in the corners, and lies down, clasping a gun. Then we hear the pulse of Corona’s disco hit “The Rhythm of the Night.” We cut to Galoup smoking in a night club, leaning against a panelled mirror. He bobs his head to the music, tracing loose arcs in the air with his cigarette. He snarls. He spins in a tight circle, smoke trailing him like a cape. Then, at the chorus, unsmiling and intent, he lets himself go, flying into the air, fingers splayed like a gecko’s. I can’t describe what it felt like watching him for the first time, more blur than human. But I remember what it did to me. I got up and I began to wave my hands above my head, alone in the dark.

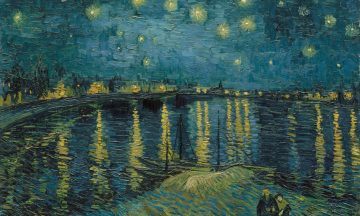

Before I knew who Claire Denis was, she taught me how to dance. When I was eighteen, it was easier to stay in with a movie than to go to a party and be surrounded by strangers. One night, I watched Denis’s film “Beau Travail,” from 1999. Afterward, I couldn’t sleep. I kept replaying the ending, transfixed by a man with a battered face, Galoup. For ninety minutes, Galoup (Denis Lavant) is small and hunched, a military officer who, after being ejected from the French Foreign Legion, can’t find meaning in civilian life. In a closing scene, he makes his bed, carefully tucking in the corners, and lies down, clasping a gun. Then we hear the pulse of Corona’s disco hit “The Rhythm of the Night.” We cut to Galoup smoking in a night club, leaning against a panelled mirror. He bobs his head to the music, tracing loose arcs in the air with his cigarette. He snarls. He spins in a tight circle, smoke trailing him like a cape. Then, at the chorus, unsmiling and intent, he lets himself go, flying into the air, fingers splayed like a gecko’s. I can’t describe what it felt like watching him for the first time, more blur than human. But I remember what it did to me. I got up and I began to wave my hands above my head, alone in the dark. As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at

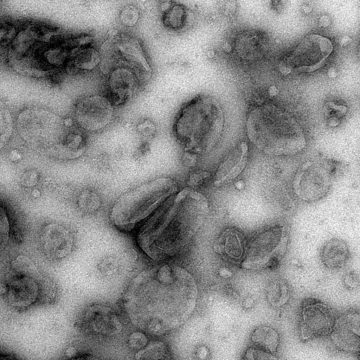

As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at  Cancer immunotherapy drugs, which spur the body’s own immune system to attack tumors, hold great promise but still fail many patients.

Cancer immunotherapy drugs, which spur the body’s own immune system to attack tumors, hold great promise but still fail many patients.

The modern world is full of technology, and also with anxiety about technology. We worry about robot uprisings and artificial intelligence taking over, and we contemplate what it would mean for a computer to be conscious or truly human. It should probably come as no surprise that these ideas aren’t new to modern society — they go way back, at least to the stories and mythologies of ancient Greece. Today’s guest, Adrienne Mayor, is a folklorist and historian of science, whose recent work has been on robots and artificial humans in ancient mythology. From the bronze warrior Talos to the evil fembot Pandora, mythology is rife with stories of artificial beings. It’s both fun and useful to think about our contemporary concerns in light of these ancient tales.

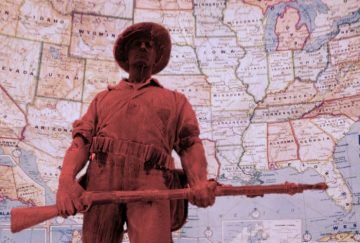

The modern world is full of technology, and also with anxiety about technology. We worry about robot uprisings and artificial intelligence taking over, and we contemplate what it would mean for a computer to be conscious or truly human. It should probably come as no surprise that these ideas aren’t new to modern society — they go way back, at least to the stories and mythologies of ancient Greece. Today’s guest, Adrienne Mayor, is a folklorist and historian of science, whose recent work has been on robots and artificial humans in ancient mythology. From the bronze warrior Talos to the evil fembot Pandora, mythology is rife with stories of artificial beings. It’s both fun and useful to think about our contemporary concerns in light of these ancient tales. I recently stumbled across a statue in Baltimore that celebrates the young men of the city who fought in the “Spanish War.” On a narrow triangle in a residential neighborhood, this lone soldier stands at ease, holding a rifle across his body and staring into the distance, unperturbed by the city buses screeching past or the litter that collects below his feet. The pedestal records the years, from 1898 to 1902, when these brave Americans fought against Spain’s weak imperialist hold on the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Known as “The Hiker,” fifty or so versions of this statue still quietly dot city streets and parks across the United States. The bulk were erected in the 1920s in northern states, with Baltimore’s in 1943, and the last in 1965 near Arlington Cemetery.

I recently stumbled across a statue in Baltimore that celebrates the young men of the city who fought in the “Spanish War.” On a narrow triangle in a residential neighborhood, this lone soldier stands at ease, holding a rifle across his body and staring into the distance, unperturbed by the city buses screeching past or the litter that collects below his feet. The pedestal records the years, from 1898 to 1902, when these brave Americans fought against Spain’s weak imperialist hold on the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Known as “The Hiker,” fifty or so versions of this statue still quietly dot city streets and parks across the United States. The bulk were erected in the 1920s in northern states, with Baltimore’s in 1943, and the last in 1965 near Arlington Cemetery. Last year saw the publication of a book that could well turn out to be a future classic of art writing. Jack Whitten’s Notes From the Woodshed was released just a few months after the painter’s death in New York at the age of 78. More than 500 pages of journal entries, written between March 24, 1962, and December 27, 2017, Notes From the Woodshed gives as true a sense of how the life of an artist is lived, and how it’s lived for the sake of his work, as any I’ve read. The book’s hallmarks are a kinetic energy of thought and immediacy of expression that trump literary style or even good spelling. By the end of his life, Whitten knew that his notes would be published—he wrote a prefatory essay in September 2015, more than two years before his last journal entry—but he didn’t gussy them up. They have been abridged, though, partly because he could be as critical of his fellow artists as he could be generously enthusiastic about them, and “a few of his writings have been redacted here to protect the living,” notes the book’s editor, Katy Siegel, who also curated last year’s exhibition, “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017,” at the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Met Breuer.

Last year saw the publication of a book that could well turn out to be a future classic of art writing. Jack Whitten’s Notes From the Woodshed was released just a few months after the painter’s death in New York at the age of 78. More than 500 pages of journal entries, written between March 24, 1962, and December 27, 2017, Notes From the Woodshed gives as true a sense of how the life of an artist is lived, and how it’s lived for the sake of his work, as any I’ve read. The book’s hallmarks are a kinetic energy of thought and immediacy of expression that trump literary style or even good spelling. By the end of his life, Whitten knew that his notes would be published—he wrote a prefatory essay in September 2015, more than two years before his last journal entry—but he didn’t gussy them up. They have been abridged, though, partly because he could be as critical of his fellow artists as he could be generously enthusiastic about them, and “a few of his writings have been redacted here to protect the living,” notes the book’s editor, Katy Siegel, who also curated last year’s exhibition, “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017,” at the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Met Breuer. The subsequent outpouring of creativity at the Bauhaus has since become the stuff of legend. Yet despite its popularity among teachers and students, the school and its methods were consistently controversial. As the clouds of nationalism gathered over Germany, many in Weimar were troubled by the blatant internationalism of the Bauhaus. Others attacked the emphasis on freedom and experimentation as inappropriately indulgent for a state-funded school. The economic uncertainties of the early 1920s only increased the pressure on Gropius. In 1925, the authorities in Weimar closed the school, forcing its relocation to Dessau, about 100 miles to the northeast.

The subsequent outpouring of creativity at the Bauhaus has since become the stuff of legend. Yet despite its popularity among teachers and students, the school and its methods were consistently controversial. As the clouds of nationalism gathered over Germany, many in Weimar were troubled by the blatant internationalism of the Bauhaus. Others attacked the emphasis on freedom and experimentation as inappropriately indulgent for a state-funded school. The economic uncertainties of the early 1920s only increased the pressure on Gropius. In 1925, the authorities in Weimar closed the school, forcing its relocation to Dessau, about 100 miles to the northeast. This familiar Strindbergian theme is underscored in The Best Intentions by an ingenious device to which the author turns more than once: the juxtaposition of some ostensibly documentary evidence from the “real life” that he’s fictionalizing—a photograph he has found of this or that relative or an entry in someone’s diary—with his novelistic reconstruction of the person or incident in question. This technique can shed ironic light on the characters. A passage, for instance, when Bergman quotes a diary entry by Henrik’s mother, Alma, after she meets her future daughter-in-law for the first time: “Henrik came with his fiancée. She is surprisingly beautiful and he seems happy. Fredrik Paulin called in the evening. He talked about tedious things from the past. That was inappropriate and made Henrik sad.”

This familiar Strindbergian theme is underscored in The Best Intentions by an ingenious device to which the author turns more than once: the juxtaposition of some ostensibly documentary evidence from the “real life” that he’s fictionalizing—a photograph he has found of this or that relative or an entry in someone’s diary—with his novelistic reconstruction of the person or incident in question. This technique can shed ironic light on the characters. A passage, for instance, when Bergman quotes a diary entry by Henrik’s mother, Alma, after she meets her future daughter-in-law for the first time: “Henrik came with his fiancée. She is surprisingly beautiful and he seems happy. Fredrik Paulin called in the evening. He talked about tedious things from the past. That was inappropriate and made Henrik sad.” Romance readers compound the sin of liking happy, sexy stories with the sin of not caring much about the opinions of serious people, which is to say, men. They are openly scornful of the outsiders who occasionally parachute in to report on them. In late 2017, Robert Gottlieb – the former editor of the New Yorker and unsurpassable embodiment of the concept “august literary man” – wrote

Romance readers compound the sin of liking happy, sexy stories with the sin of not caring much about the opinions of serious people, which is to say, men. They are openly scornful of the outsiders who occasionally parachute in to report on them. In late 2017, Robert Gottlieb – the former editor of the New Yorker and unsurpassable embodiment of the concept “august literary man” – wrote  Not long ago I diagnosed myself with the recently identified condition of sidewalk rage. It’s most pronounced when it comes to a certain friend who is a slow walker. Last month, as we sashayed our way to dinner, I found myself biting my tongue, thinking, I have to stop going places with her if I ever want to … get there! You too can measure yourself on the “Pedestrian Aggressiveness Syndrome Scale,” a tool developed by University of Hawaii psychologist Leon James. While walking in a crowd, do you find yourself “acting in a hostile manner (staring, presenting a mean face, moving closer or faster than expected)” and “enjoying thoughts of violence?”

Not long ago I diagnosed myself with the recently identified condition of sidewalk rage. It’s most pronounced when it comes to a certain friend who is a slow walker. Last month, as we sashayed our way to dinner, I found myself biting my tongue, thinking, I have to stop going places with her if I ever want to … get there! You too can measure yourself on the “Pedestrian Aggressiveness Syndrome Scale,” a tool developed by University of Hawaii psychologist Leon James. While walking in a crowd, do you find yourself “acting in a hostile manner (staring, presenting a mean face, moving closer or faster than expected)” and “enjoying thoughts of violence?” The

The

We are at an inflection point in the Democratic Party’s history, and in the economic history of the country; similar, perhaps, to the mid-1930s and the late-1970s. In the first period, the country embraced Keynesian, demand-side economics. In the second, during a time of pummeling inflation and wage stagnation, the country turned away from Keynes and toward Milton Friedman and supply-side economics.

We are at an inflection point in the Democratic Party’s history, and in the economic history of the country; similar, perhaps, to the mid-1930s and the late-1970s. In the first period, the country embraced Keynesian, demand-side economics. In the second, during a time of pummeling inflation and wage stagnation, the country turned away from Keynes and toward Milton Friedman and supply-side economics.