Stuart Schrader in the Boston Review:

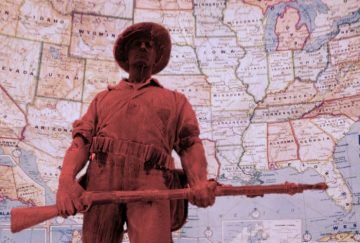

I recently stumbled across a statue in Baltimore that celebrates the young men of the city who fought in the “Spanish War.” On a narrow triangle in a residential neighborhood, this lone soldier stands at ease, holding a rifle across his body and staring into the distance, unperturbed by the city buses screeching past or the litter that collects below his feet. The pedestal records the years, from 1898 to 1902, when these brave Americans fought against Spain’s weak imperialist hold on the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Known as “The Hiker,” fifty or so versions of this statue still quietly dot city streets and parks across the United States. The bulk were erected in the 1920s in northern states, with Baltimore’s in 1943, and the last in 1965 near Arlington Cemetery.

I recently stumbled across a statue in Baltimore that celebrates the young men of the city who fought in the “Spanish War.” On a narrow triangle in a residential neighborhood, this lone soldier stands at ease, holding a rifle across his body and staring into the distance, unperturbed by the city buses screeching past or the litter that collects below his feet. The pedestal records the years, from 1898 to 1902, when these brave Americans fought against Spain’s weak imperialist hold on the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Known as “The Hiker,” fifty or so versions of this statue still quietly dot city streets and parks across the United States. The bulk were erected in the 1920s in northern states, with Baltimore’s in 1943, and the last in 1965 near Arlington Cemetery.

Their anti-imperialist sentiment resonated with a different kind of monument that emerged in the same period—those to the Confederacy. To numerous white Americans, the democratic reconstruction of the former Confederacy was an imperialist exercise, and both types of statue celebrated a fight against empire. But they mobilized a rose-tinted vision of past war-making to reject the contemporary reality of early twentieth-century U.S. statecraft: Washington had built an empire, subjecting millions with dark skin to its rule. The anti-imperialist sentiment implicit in the statues, whatever its source, did not curtail empire. It denied its existence.

These monuments—both to the Confederacy and to far-flung operations and occupations—reveal just how vexing the term “empire” is in the U.S. vocabulary.

More here.