Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian:

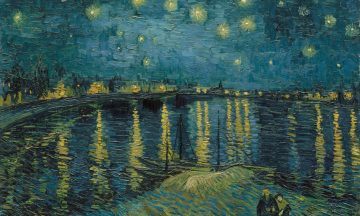

As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at Tate Britain, it is, in one sense, coming home. This might sound like wishful thinking. For the past half century the painting has hung in Paris, and its singing Mediterranean colours, which the artist himself described as “aquamarine”, “royal blue” and “russet gold”, bear little resemblance to the murky half-tints of the Thames, which runs past Tate Britain’s Millbank site. Yet its spring exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain, is organised on the principle that the foundations of the Dutchman’s art, both his eye and his intellect, were laid not in the south of France, nor in the misty light of the Low Countries, but in London, where he spent three life-defining years (1873-76) as a young man.

As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at Tate Britain, it is, in one sense, coming home. This might sound like wishful thinking. For the past half century the painting has hung in Paris, and its singing Mediterranean colours, which the artist himself described as “aquamarine”, “royal blue” and “russet gold”, bear little resemblance to the murky half-tints of the Thames, which runs past Tate Britain’s Millbank site. Yet its spring exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain, is organised on the principle that the foundations of the Dutchman’s art, both his eye and his intellect, were laid not in the south of France, nor in the misty light of the Low Countries, but in London, where he spent three life-defining years (1873-76) as a young man.

A case in point: if you look beyond the hallucinogenic brilliance of Starry Night Over the Rhône, which Van Gogh painted in 1888, two years before his death, you will notice a family resemblance to a small black and white engraving that he first encountered more than a decade earlier, during his London stay. Gustave Doré’s Evening on the Thames shows London from Westminster Bridge, a view Van Gogh knew intimately from his commute between his suburban lodgings and the Covent Garden office where he worked as a clerk. It wasn’t the pomp of the neo-gothic Houses of Parliament that drew Van Gogh to Doré’s image so much as the regular pattern made by the gaslights as they flared across the river. Fifteen years later he would transpose this jolt of modernity to Starry Night Over the Rhône, a view of Arles in which new-fangled streetlamps compete with exploding stars to light up the sky.

More here.