Morgan Meis in The Easel:

It should be mentioned that Backyard is a huge C-Print (91 X 150 inches) mounted on plexiglass and without any frame. The mundanity of the image is therefore partially offset by its commanding presence. Looking at the large, high resolution image, one can study the details of the scene. A few minutes of such study generally creates a sense of unease in the viewer. Something is wrong here. The problem is not so much in the overall content of the scene, or in its composition. Rather, many of the details in the picture just don’t look right. There are, for instance, several small pieces of dirt and refuse on the concrete steps that lead up to the door of the house on the right of the picture. But the bits of dirt do not look like real dirt. The dirt just isn’t dirty enough to be real dirt. Nor, at second glance, is the concrete rough and heavy enough in its appearance to be real concrete. And the light – the illumination on the steps doesn’t seem at all consistent with the overcast sky, just beyond those blossoming trees.

The secret is that Backyard is not a photograph of a real backyard at all. It is a photograph of a “fake” backyard, a life-sized model of a backyard made by Demand out of paper and cardboard. Even the beautifully flowering trees in the background are paper models. The plastic is not plastic, it is colored cardboard. Every single object in the picture has been constructed by Demand (and his assistants), which he then photographed. After the photograph was taken, the cardboard and paper model was destroyed. So, the photograph is the only documentation of the existence of this backyard.

More here.

Despite the lowest unemployment rates since the late 1960s, the American economy is failing its citizens. Some 90 percent have seen their incomes stagnate or decline in the past 30 years. This is not surprising, given that the

Despite the lowest unemployment rates since the late 1960s, the American economy is failing its citizens. Some 90 percent have seen their incomes stagnate or decline in the past 30 years. This is not surprising, given that the  When we talk about the mind, we are constantly talking about consciousness and cognition. Antonio Damasio wants us to talk about our feelings. But it’s not in an effort to be more touchy-feely; Damasio, one of the world’s leading neuroscientists, believes that feelings generated by the body are a crucial part of how we achieve and maintain homeostasis, which in turn is a key driver in understanding who we are. His most recent book,

When we talk about the mind, we are constantly talking about consciousness and cognition. Antonio Damasio wants us to talk about our feelings. But it’s not in an effort to be more touchy-feely; Damasio, one of the world’s leading neuroscientists, believes that feelings generated by the body are a crucial part of how we achieve and maintain homeostasis, which in turn is a key driver in understanding who we are. His most recent book,  It’s 7pm on a Sunday, and night is falling in this Michoacán town. The heat of the day is past, and there’s a pleasant breeze. The first visitors to the park have left for dinner, but many hang around.

It’s 7pm on a Sunday, and night is falling in this Michoacán town. The heat of the day is past, and there’s a pleasant breeze. The first visitors to the park have left for dinner, but many hang around.

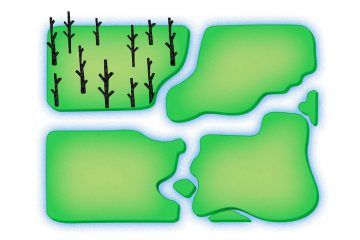

Foresters began noticing the patches of dying pines and denuded oaks, and grew concerned. Warmer winters and drier summers had sent invasive insects and diseases marching northward, killing the trees. If the dieback continued, some woodlands could become shrub land. Most trees can migrate only as fast as their seeds disperse — and if current warming trends hold, the climate this century will change 10 times faster than many tree species can move, according to

Foresters began noticing the patches of dying pines and denuded oaks, and grew concerned. Warmer winters and drier summers had sent invasive insects and diseases marching northward, killing the trees. If the dieback continued, some woodlands could become shrub land. Most trees can migrate only as fast as their seeds disperse — and if current warming trends hold, the climate this century will change 10 times faster than many tree species can move, according to

Alongside cryptic epigraphs from F Scott Fitzgerald and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the only-partially-reformed slam poet HM Naqvi began his debut novel Home Boy with a couplet from that most writerly act of old-school rap, Eric B & Rakim.

Alongside cryptic epigraphs from F Scott Fitzgerald and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the only-partially-reformed slam poet HM Naqvi began his debut novel Home Boy with a couplet from that most writerly act of old-school rap, Eric B & Rakim. Design submissions for the restoration of

Design submissions for the restoration of  In early 1933, in the final days of the Weimar Republic, Eric Hobsbawm was in Berlin. He had lost his parents, and his uncle and aunt had taken him to Berlin where he joined his younger sister. As a teenaged student, Hobsbawm saw Germany falling into the hands of the Nazis. Hitler’s Brownshirts were unleashing widespread violence on the streets of Berlin. The country’s economy was in a shambles. Political instability was at its peak and the Nazi party was growing in popularity. Those were the formative years of the political Hobsbawm. “In this highly politicised atmosphere, it was perhaps hardly surprising that Eric soon became interested in the communist cause,” writes Richard J. Evans in Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History, a biography of one of the most renowned historians of the 20th century.

In early 1933, in the final days of the Weimar Republic, Eric Hobsbawm was in Berlin. He had lost his parents, and his uncle and aunt had taken him to Berlin where he joined his younger sister. As a teenaged student, Hobsbawm saw Germany falling into the hands of the Nazis. Hitler’s Brownshirts were unleashing widespread violence on the streets of Berlin. The country’s economy was in a shambles. Political instability was at its peak and the Nazi party was growing in popularity. Those were the formative years of the political Hobsbawm. “In this highly politicised atmosphere, it was perhaps hardly surprising that Eric soon became interested in the communist cause,” writes Richard J. Evans in Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History, a biography of one of the most renowned historians of the 20th century. Imagine the outcry if, at the 2016 Summer Olympics, the legendary United States swim team – Michael Phelps, Ryan Lochte, Conor Dwyer and Townley Haas – still obliterated the competition, coming first in the men’s 4 x 200m freestyle relay, but only Haas, Lochte and Dwyer received medals, with nothing, not even a silver, for Phelps. ‘Unfair!’ you’d cry. And you’d be right.

Imagine the outcry if, at the 2016 Summer Olympics, the legendary United States swim team – Michael Phelps, Ryan Lochte, Conor Dwyer and Townley Haas – still obliterated the competition, coming first in the men’s 4 x 200m freestyle relay, but only Haas, Lochte and Dwyer received medals, with nothing, not even a silver, for Phelps. ‘Unfair!’ you’d cry. And you’d be right. Arthur Brooks is one of the limitless number of policy analysts who toil in Washington. He stands out both because he is prolific and his work has had an impact. He has already written 10 books on a wide range of subjects, served as president of the influential center-right American Enterprise Institute, and writes a column for the Washington Post. His background sets him apart. An accomplished classical musician, he spent 12 years playing in a symphony orchestra. He worked his way through college and attended Thomas Edison State University in New Jersey – not exactly a “big name” school in the corridors of power (though he did earn a Ph.D. in public policy from the Rand Institute). On a personal level, he is deeply religious (Roman Catholic) and calls the Dalai Lama a friend and mentor.

Arthur Brooks is one of the limitless number of policy analysts who toil in Washington. He stands out both because he is prolific and his work has had an impact. He has already written 10 books on a wide range of subjects, served as president of the influential center-right American Enterprise Institute, and writes a column for the Washington Post. His background sets him apart. An accomplished classical musician, he spent 12 years playing in a symphony orchestra. He worked his way through college and attended Thomas Edison State University in New Jersey – not exactly a “big name” school in the corridors of power (though he did earn a Ph.D. in public policy from the Rand Institute). On a personal level, he is deeply religious (Roman Catholic) and calls the Dalai Lama a friend and mentor. As the French novelist Albert Camus said, life is “absurd,” without meaning. This was not the opinion of folk in the Middle Ages. A very nice young Christian and I have recently edited a history of atheism. We had a devil of a job – to use a phrase – finding people to write on that period. In the West, Christianity filled the gaps and gave life full meaning. The claims about our Creator God and his son Jesus Christ, combined with the rituals and extended beliefs, especially about the Virgin Mary, meant that everyone’s life, to use a cliché from prince to pauper, made good sense. The promises of happiness in the eternal hereafter were cherished and appreciated by everyone and the expectations put on a godly person made for a functioning society.

As the French novelist Albert Camus said, life is “absurd,” without meaning. This was not the opinion of folk in the Middle Ages. A very nice young Christian and I have recently edited a history of atheism. We had a devil of a job – to use a phrase – finding people to write on that period. In the West, Christianity filled the gaps and gave life full meaning. The claims about our Creator God and his son Jesus Christ, combined with the rituals and extended beliefs, especially about the Virgin Mary, meant that everyone’s life, to use a cliché from prince to pauper, made good sense. The promises of happiness in the eternal hereafter were cherished and appreciated by everyone and the expectations put on a godly person made for a functioning society. For me — and, I suspect, for many others — my crush on Rogers has something to do with seeing a man play, and make-believe, and talk openly about his feelings; it’s about what it means to see a man not acting like “a man” at all. And the excitement of that — political, ethical, and, yes, sexual. What would it be like, I wonder as I watch Rogers, to fuck a man who rejects masculinity? How does Rogers, embodying this alternative, make us think about sex, about who it is safe to do it with, and how, and why, and who we become when we fuck, and what hurts when we do, and what might feel good, and what never did, and why our sex is so often marked by violence, physical or mental or emotional. The Rogers phenomenon is about what masculinity might look like if one rejects its patriarchal construction; it’s about the fear of — and intense desire for — a radical alternative.

For me — and, I suspect, for many others — my crush on Rogers has something to do with seeing a man play, and make-believe, and talk openly about his feelings; it’s about what it means to see a man not acting like “a man” at all. And the excitement of that — political, ethical, and, yes, sexual. What would it be like, I wonder as I watch Rogers, to fuck a man who rejects masculinity? How does Rogers, embodying this alternative, make us think about sex, about who it is safe to do it with, and how, and why, and who we become when we fuck, and what hurts when we do, and what might feel good, and what never did, and why our sex is so often marked by violence, physical or mental or emotional. The Rogers phenomenon is about what masculinity might look like if one rejects its patriarchal construction; it’s about the fear of — and intense desire for — a radical alternative. What Overton proposes is a sort of grand unified theory of suicide bombing, tracing a thread of bloody utopian thinking through a century or so of self-destructive murder, where the act prefigured either an idea of self-sacrifice for a greater good or reflected the religious conviction that the self continues.

What Overton proposes is a sort of grand unified theory of suicide bombing, tracing a thread of bloody utopian thinking through a century or so of self-destructive murder, where the act prefigured either an idea of self-sacrifice for a greater good or reflected the religious conviction that the self continues.