by Richard King

I was just four months old when the Pentagon Papers were published in 1971, but I remember very distinctly the mixed emotions that ran through my mind when I first clapped eyes on that historic edition of the New York Times in my local library. For here was everything I loathed and loved in one incredible revelation! On the one hand, imperialism, war and corruption. On the other, the First Amendment and the Fourth Estate. "Mother," I said, as she swiped the paper from the hands of a startled pensioner, "Mother, darling – mark this day! For though a dark cloud in the progress of our species, it has about it a silver lining that in future years will be as a beacon to good men and women of the press the world over! Dry your eyes, mother mine. Here, use my handkerchief." I was a precocious child.

I was just four months old when the Pentagon Papers were published in 1971, but I remember very distinctly the mixed emotions that ran through my mind when I first clapped eyes on that historic edition of the New York Times in my local library. For here was everything I loathed and loved in one incredible revelation! On the one hand, imperialism, war and corruption. On the other, the First Amendment and the Fourth Estate. "Mother," I said, as she swiped the paper from the hands of a startled pensioner, "Mother, darling – mark this day! For though a dark cloud in the progress of our species, it has about it a silver lining that in future years will be as a beacon to good men and women of the press the world over! Dry your eyes, mother mine. Here, use my handkerchief." I was a precocious child.

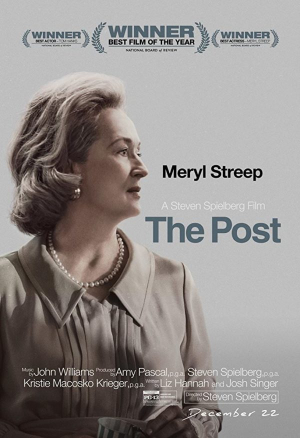

It would be nice, would it not, to rewrite history in a way that made ourselves central to the story, and that made us appear more relevant and prescient and brilliant than we actually are. It would be ludicrous as well, of course, though that doesn't stop some people doing it, especially those who write for a living. I've grumbled before that the "media culpa" following the 2016 US election disguised a deep strain of self-congratulation, as the dead-tree press and major stations affected to glorify themselves with faint praise. ("If only we'd had our game-face on, this tragedy might never have happened!") Now I must return to the subject, one Steven Spielberg having entered the field with a film that polishes the MSM's image to a high and self-reflecting shine. The Post is rather good, as it happens; but it's also very, very bad.

The key points in the narrative are a matter of historical record, so I imagine we can dispense with the spoiler alerts. In 1969 military analyst Daniel Ellsberg made photocopies of ‘the Pentagon Papers', aka United States–Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense. The documents revealed, inter alia, that the US government had lied "systematically" about the ongoing war in Vietnam and that it had secretly spread the war to Cambodia and Laos. Ellsberg passed the documents to Neil Sheehan, a reporter for the New York Times, and on June 13, 1971, the Times published the first of nine excerpts from the Papers, together with editorial commentaries. On June 15, the Nixon administration sought, and was granted, a court injunction preventing further publication, so Ellsberg passed copies of the documents to Ben Bagdikian at the Washington Post. After much agonising and internal argument, and in defiance of the Attorney General, the Post began running its own series of articles on the Papers on June 18. On June 30, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the New York Times, putting the Post (and other papers) in the clear.

Read more »

Christian Wiman at The American Scholar: