Adam Gopnik at The New Yorker:

Taylor’s new book is formidably chewy, with page after page featuring passages of Hölderlin, Novalis, and Rilke, offered both in the original German and in translation. Long analyses of T. S. Eliot and Milosz arrive, too. But, though Taylor’s subjects are often severely abstract, his sentences are lucid, even charmingly direct, and his purpose is plain. We once lived in an “enchanted” universe of agreed-upon meaning and common purpose, where we looked at the night sky and felt that each object was shaped with significance by a God-given order. Now we live in the modern world the Enlightenment produced—one of fragmented belief and broken purposes, where no God superintends the cosmos, common agreement on meaning is no longer possible, and all you can do with the moon is measure it. “I admire the moon as a moon, just a moon,” Lorenz Hart sighed, with memorable modernity, adding, significantly, “Nobody’s heart belongs to me today.” Enlightened, we are alone.

Taylor’s new book is formidably chewy, with page after page featuring passages of Hölderlin, Novalis, and Rilke, offered both in the original German and in translation. Long analyses of T. S. Eliot and Milosz arrive, too. But, though Taylor’s subjects are often severely abstract, his sentences are lucid, even charmingly direct, and his purpose is plain. We once lived in an “enchanted” universe of agreed-upon meaning and common purpose, where we looked at the night sky and felt that each object was shaped with significance by a God-given order. Now we live in the modern world the Enlightenment produced—one of fragmented belief and broken purposes, where no God superintends the cosmos, common agreement on meaning is no longer possible, and all you can do with the moon is measure it. “I admire the moon as a moon, just a moon,” Lorenz Hart sighed, with memorable modernity, adding, significantly, “Nobody’s heart belongs to me today.” Enlightened, we are alone.

Romantic poetry—the poetry of Shelley and Keats, in English, of Novalis and Hölderlin, in German—first diagnosed this fracture (the argument goes) and offered a way to heal it. Where neoclassical poets like Alexander Pope appealed to an ordered world, with clear meanings and a hierarchy of kinds, the Romantics recognized that this was no longer credible.

more here.

In Glynnis MacNicol’s second memoir,

In Glynnis MacNicol’s second memoir,

R

R You might have encountered Jehovah’s Witnesses before as the conservatively dressed religious types knocking on your front door, offering copies of The Watchtower, a free magazine promoting their faith. But there’s a darker side to this religious group, whose estimated 8 million members worldwide believe we are living in the “last days.” For the latest episode of

You might have encountered Jehovah’s Witnesses before as the conservatively dressed religious types knocking on your front door, offering copies of The Watchtower, a free magazine promoting their faith. But there’s a darker side to this religious group, whose estimated 8 million members worldwide believe we are living in the “last days.” For the latest episode of  The Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, UK, is a world leader in basic biology research. The lab’s list of breakthroughs is enviable, from the structure of DNA and proteins to genetic sequencing. Since its origins in the late 1940s, the institute — currently with around 700 staff members — has produced a dozen Nobel prizewinners, including DNA decipherers James Watson, Francis Crick and Fred Sanger. Four LMB scientists received their awards in the past 15 years:

The Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, UK, is a world leader in basic biology research. The lab’s list of breakthroughs is enviable, from the structure of DNA and proteins to genetic sequencing. Since its origins in the late 1940s, the institute — currently with around 700 staff members — has produced a dozen Nobel prizewinners, including DNA decipherers James Watson, Francis Crick and Fred Sanger. Four LMB scientists received their awards in the past 15 years:  There are two irrefutable axioms that can be made about jazz. The first is that jazz is America’s most significant cultural contribution to the world; the second is that jazz was mostly, though not entirely, a contribution born from the experience and brilliance of America’s Black populace who have rarely been treated as full citizens. Regarding the first claim, if the genre is not America’s “classical music,” for there is a bit of a category mistake in Wynton Marsalis’s contention which judges the music by such standards, then jazz is certainly the most indispensable and quintessential of American creations, surpassing in significance other novelties, from comic books to Hollywood films. Crouch describes Ellington, and by proxy jazz, as “maybe the most American of Americans,” even while the conservative critic was long an advocate for the music as being fundamentally our native “classical” (a role for which he was influential as Marsalis’s adviser as director of jazz at Lincoln Center). The desire to transform jazz into classical music—even my own comparison of Ellington to Bach—is an insulting reduction of the music’s innovation. Jazz doesn’t need to be classical music, it’s already jazz.

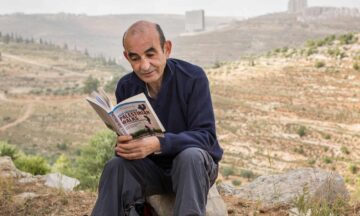

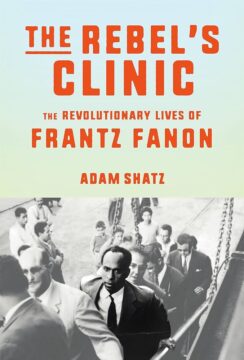

There are two irrefutable axioms that can be made about jazz. The first is that jazz is America’s most significant cultural contribution to the world; the second is that jazz was mostly, though not entirely, a contribution born from the experience and brilliance of America’s Black populace who have rarely been treated as full citizens. Regarding the first claim, if the genre is not America’s “classical music,” for there is a bit of a category mistake in Wynton Marsalis’s contention which judges the music by such standards, then jazz is certainly the most indispensable and quintessential of American creations, surpassing in significance other novelties, from comic books to Hollywood films. Crouch describes Ellington, and by proxy jazz, as “maybe the most American of Americans,” even while the conservative critic was long an advocate for the music as being fundamentally our native “classical” (a role for which he was influential as Marsalis’s adviser as director of jazz at Lincoln Center). The desire to transform jazz into classical music—even my own comparison of Ellington to Bach—is an insulting reduction of the music’s innovation. Jazz doesn’t need to be classical music, it’s already jazz. Fanon’s trickiness lies in how he seduces the reader with a moral outrage that he immediately deconstructs. Starting from a position of anti-colonial fury, his books ascend to a universalist crescendo. This can function like a trap for any reader who wants a monolithic Fanon, whether revolutionary or humanist, nationalist or internationalist, romantic or realist. Rather than stabilize him, we must allow him to be both—sometimes at once but at other times in progression. We must accept the dialectical Fanon, a thinker larger than the mutually defining opposites he described. To understand him, we cannot split him, as the psychiatrists would say. For in protecting Fanon from one aspect of himself, we ultimately end up trying to protect ourselves.

Fanon’s trickiness lies in how he seduces the reader with a moral outrage that he immediately deconstructs. Starting from a position of anti-colonial fury, his books ascend to a universalist crescendo. This can function like a trap for any reader who wants a monolithic Fanon, whether revolutionary or humanist, nationalist or internationalist, romantic or realist. Rather than stabilize him, we must allow him to be both—sometimes at once but at other times in progression. We must accept the dialectical Fanon, a thinker larger than the mutually defining opposites he described. To understand him, we cannot split him, as the psychiatrists would say. For in protecting Fanon from one aspect of himself, we ultimately end up trying to protect ourselves. With increasing availability and sophistication of chatbots, we teachers are seeing a drastic decline in the cost of what in Great Britain is called “commissioning”—that is, getting someone else to do your academic work for you. There are many forms of academic cheating, at various levels of schooling, but commissioning by university students is the one I want to discuss today.

With increasing availability and sophistication of chatbots, we teachers are seeing a drastic decline in the cost of what in Great Britain is called “commissioning”—that is, getting someone else to do your academic work for you. There are many forms of academic cheating, at various levels of schooling, but commissioning by university students is the one I want to discuss today. Once you start thinking about computation, you start to see it everywhere. Take mailing a letter through the postal service. Put the letter in an envelope with an address and a stamp on it, and stick it in a mailbox, and somehow it will end up in the recipient’s mailbox. That is a computational process — a series of operations that move the letter from one place to another until it reaches its final destination. This routing process is not unlike what happens with electronic mail or any other piece of data sent through the internet. Seeing the world in this way may seem odd, but as Friedrich Nietzsche is reputed to have said, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

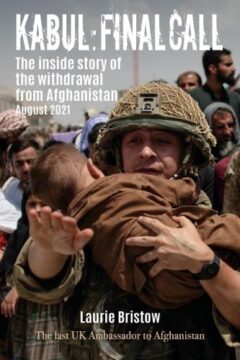

Once you start thinking about computation, you start to see it everywhere. Take mailing a letter through the postal service. Put the letter in an envelope with an address and a stamp on it, and stick it in a mailbox, and somehow it will end up in the recipient’s mailbox. That is a computational process — a series of operations that move the letter from one place to another until it reaches its final destination. This routing process is not unlike what happens with electronic mail or any other piece of data sent through the internet. Seeing the world in this way may seem odd, but as Friedrich Nietzsche is reputed to have said, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.” What went wrong? As Bristow tells it, the west failed because of bad strategy and a loss of will. After the attacks on the twin towers, a military response from the US and its allies was inevitable. Its goal: to exterminate al-Qaeda. As a young reporter,

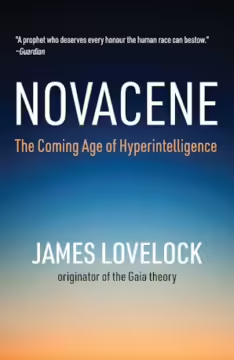

What went wrong? As Bristow tells it, the west failed because of bad strategy and a loss of will. After the attacks on the twin towers, a military response from the US and its allies was inevitable. Its goal: to exterminate al-Qaeda. As a young reporter,  What is today called “artificial intelligence” should be counted as a Copernican Trauma in the making. It reveals that intelligence, cognition, even mind (definitions of these historical terms are clearly up for debate) are not what they seem to be, not what they feel like, and not unique to the human condition. Obviously, the creative and technological sapience necessary to artificialize intelligence is a human accomplishment, but now, that sapience is remaking itself. Since the paleolithic cognitive revolution, human intelligence has artificialized many things — shelter, heat, food, energy, images, sounds, even life itself — but now, that intelligence itself is

What is today called “artificial intelligence” should be counted as a Copernican Trauma in the making. It reveals that intelligence, cognition, even mind (definitions of these historical terms are clearly up for debate) are not what they seem to be, not what they feel like, and not unique to the human condition. Obviously, the creative and technological sapience necessary to artificialize intelligence is a human accomplishment, but now, that sapience is remaking itself. Since the paleolithic cognitive revolution, human intelligence has artificialized many things — shelter, heat, food, energy, images, sounds, even life itself — but now, that intelligence itself is  A

A In March, the first lady, Jill Biden, announced a new

In March, the first lady, Jill Biden, announced a new