Muneeza Shamsie in Newsweek Pakistan:

This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research.

This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research.

Through his exploration of the relationship between the Christian kings of Aragon in medieval Spain and their privileged, deeply religious Muslim soldiers, the jenets in the 13th and 14th centuries, Fancy sheds new light into “the interactions between Muslims and Christians in the Middle Ages” in a bid to “rethink the study of religion more broadly.” He questions the view of modern scholars that these Muslim-Christian alliances were essentially political and secular. He concludes instead that the Muslim jenetswere deeply religious. They were originally Berbers from North Africa where they were known as al Ghuzah al Mujahid and their collaboration with the Christian kings of Aragon “was neither opposed to something called religion, nor reducible to it.”

More here.

Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him.

Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him. It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own.

It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own. Emily Wilson in The New Statesman:

Emily Wilson in The New Statesman: Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation:

Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation: Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman:

Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman: Brian Resnick in Vox:

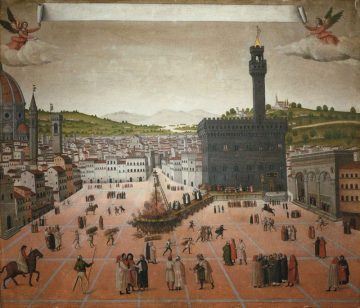

Brian Resnick in Vox: “Lent” opens with a beautifully rendered retelling of the life of Savonarola: his visions of demons, his prophecy, his political meddling and his role in vast historical forces tearing apart Italy and France. We meet a cast of characters, each with the ringing verisimilitude of well-researched, real historical personages from the heretical Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola to the statesman Lorenzo de’ Medici and various clergy, peasants, nuns and friars of feuding orders. Finally, we come to the martyrdom of Savonarola, hanged over a roaring flame, then cut down to fall into the blaze …

“Lent” opens with a beautifully rendered retelling of the life of Savonarola: his visions of demons, his prophecy, his political meddling and his role in vast historical forces tearing apart Italy and France. We meet a cast of characters, each with the ringing verisimilitude of well-researched, real historical personages from the heretical Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola to the statesman Lorenzo de’ Medici and various clergy, peasants, nuns and friars of feuding orders. Finally, we come to the martyrdom of Savonarola, hanged over a roaring flame, then cut down to fall into the blaze … T

T That

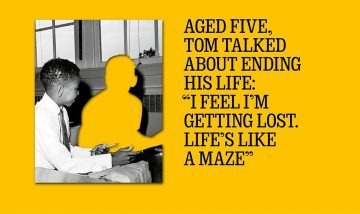

That  Tom remembers the day he decided he wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist. He was deep into research about black holes, and had amassed a box of papers on his theories. In one he speculated about the relationship between black holes and white holes, hypothetical celestial objects that emit colossal amounts of energy. Black holes, he thought, must be linked across space-time with white holes. “I put them together and I thought, oh wow, that works! That’s when I knew I wanted to do this as a job.” Tom didn’t know enough maths to prove his theory, but he had time to learn. He was only five. Tom is now 11. At home, his favourite way to relax is to devise maths exam papers complete with marking sheets. Last year for Christmas he asked his parents for the £125 registration fee to sit maths

Tom remembers the day he decided he wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist. He was deep into research about black holes, and had amassed a box of papers on his theories. In one he speculated about the relationship between black holes and white holes, hypothetical celestial objects that emit colossal amounts of energy. Black holes, he thought, must be linked across space-time with white holes. “I put them together and I thought, oh wow, that works! That’s when I knew I wanted to do this as a job.” Tom didn’t know enough maths to prove his theory, but he had time to learn. He was only five. Tom is now 11. At home, his favourite way to relax is to devise maths exam papers complete with marking sheets. Last year for Christmas he asked his parents for the £125 registration fee to sit maths  The work of the AgeLab is shaped by a paradox. Having been established to engineer and promote new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged, the AgeLab swiftly discovered that engineering and promoting new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged is a good way of going out of business. Old people will not buy anything that reminds them that they are old. They are a market that cannot be marketed to. In effect, to accept help in getting out of the suit is to accept that we’re in the suit for life. We would rather suffer because we’re old than accept that we’re old and suffer less.

The work of the AgeLab is shaped by a paradox. Having been established to engineer and promote new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged, the AgeLab swiftly discovered that engineering and promoting new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged is a good way of going out of business. Old people will not buy anything that reminds them that they are old. They are a market that cannot be marketed to. In effect, to accept help in getting out of the suit is to accept that we’re in the suit for life. We would rather suffer because we’re old than accept that we’re old and suffer less. I am truly honored to have been invited by PEN America to deliver this year’s Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. What better time than this to think together about a place for literature, at this moment when an era that we think we understand – at least vaguely, if not well – is coming to a close.

I am truly honored to have been invited by PEN America to deliver this year’s Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. What better time than this to think together about a place for literature, at this moment when an era that we think we understand – at least vaguely, if not well – is coming to a close. The scent of lily of the valley cannot be easily bottled. For decades companies that make soap, lotions and perfumes have relied on a chemical called bourgeonal to imbue their products with the sweet smell of the little white flowers. A tiny drop can be extraordinarily intense.

The scent of lily of the valley cannot be easily bottled. For decades companies that make soap, lotions and perfumes have relied on a chemical called bourgeonal to imbue their products with the sweet smell of the little white flowers. A tiny drop can be extraordinarily intense.