Tim Sahay and Kate Mackenzie in Polycrisis:

On June 25, crowning a dramatic, nationwide tax revolt, demonstrators in Nairobi stormed Kenya’s parliament buildings. President William Ruto’s new finance bill, introduced in Parliament in May, sought to increase levies on everything from bread and money transfers to sanitary items and cellular data. In response, the “Gen-Z” generation that has been criticized for not being politically active took it upon themselves to organize on TikTok and mobilize in the streets.

The public mood was souring even before the social explosion. Last year, Kenyans reported the second highest share of people struggling to eat globally, and the highest share of people fearing political unrest that would lead to violence. Public services have deteriorated rapidly with hospitals virtually empty, running out of essential medicines, and doctors striking for pay and better funded facilities. Since mid-2021, Kenya has spent twice as much on interest payments as on health. Joblessness is rising.

Kenya is not alone in its crisis. The majority of the world’s governments have undertaken austerity policies, under either direct IMF pressure or the indirect discipline of other creditors. Last spring, we warned that such moves would cause societies to boil. According to the World Bank, three in five low-income countries are now at risk of, or are already in, debt distress. No less than twenty-one sub-saharan African countries are in an IMF program. Eighteen countries defaulted between 2021 and 2023, but balance sheet calamities rarely get the attention of the international media—until social crises, dramatic protests, and violent repression break through.

More here.

S

S In the opening sentence of her rage-swollen “Ask Not,” Maureen Callahan declares that her book “is not ideological or partisan.” It is, of course, both. Sometimes it is both in extremis. You need only cast an eye over its cover, which, like the book itself, is black and white and red all over. Bad men wronging good women: cheating on them, abandoning them, infecting them, turning them into alcoholics, leaving them for dead, raping and maiming and killing them.

In the opening sentence of her rage-swollen “Ask Not,” Maureen Callahan declares that her book “is not ideological or partisan.” It is, of course, both. Sometimes it is both in extremis. You need only cast an eye over its cover, which, like the book itself, is black and white and red all over. Bad men wronging good women: cheating on them, abandoning them, infecting them, turning them into alcoholics, leaving them for dead, raping and maiming and killing them. Immediately after the attack, a photograph circulated of Rushdie being wheeled to an emergency helicopter; the volume of blood and the places he was bleeding from didn’t look promising. The longer the information gap stretched, the eerier our preparation for a post-Rushdie world became, one we’d feared even after Iran effectively

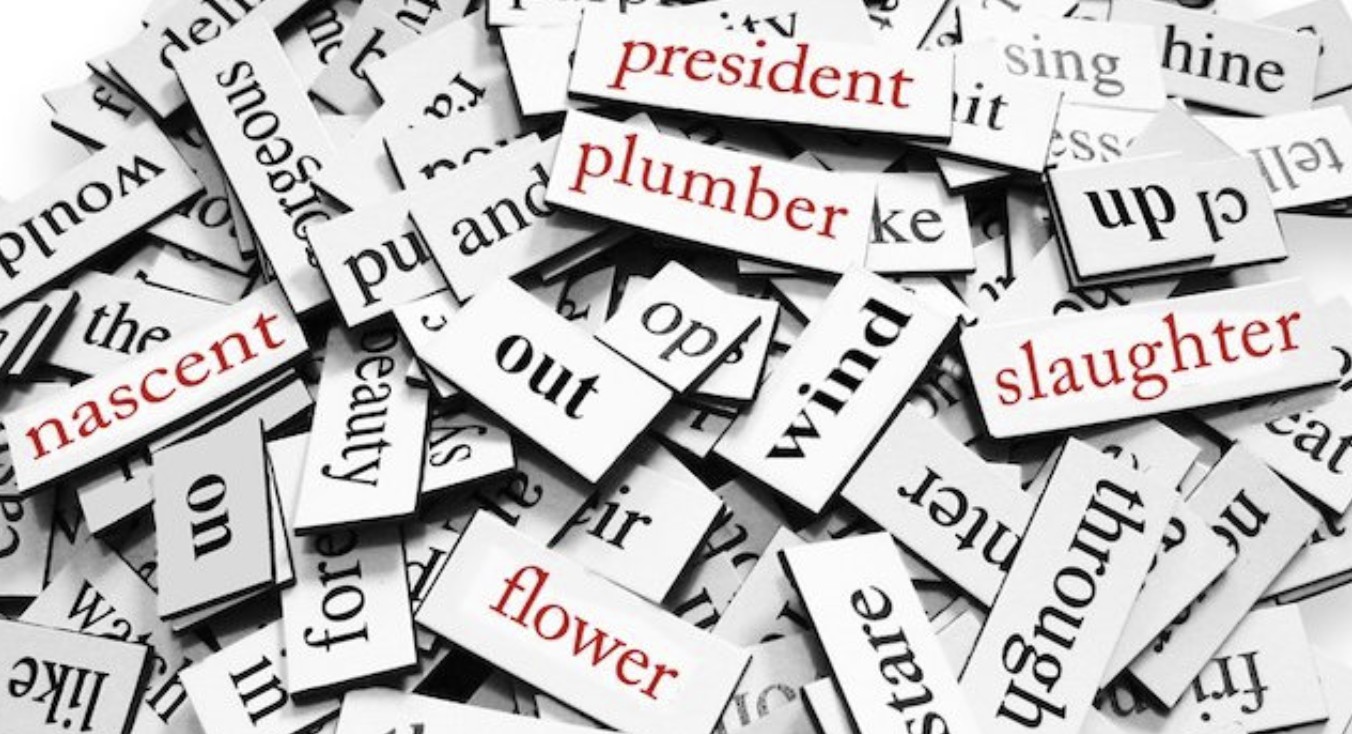

Immediately after the attack, a photograph circulated of Rushdie being wheeled to an emergency helicopter; the volume of blood and the places he was bleeding from didn’t look promising. The longer the information gap stretched, the eerier our preparation for a post-Rushdie world became, one we’d feared even after Iran effectively  How children learn language has long been of interest to those concerned with its evolution. The idea that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ has been promoted, which means the stages of child development on their way to adulthood replicate those of our human ancestors on their way to becoming modern humans. This idea has been applied to language acquisition and its evolution, but I’ve never been persuaded. It is intellectually problematic because our human ancestors were never ‘on their way’ to anywhere other than being themselves. My interest in language acquisition is different and twofold.

How children learn language has long been of interest to those concerned with its evolution. The idea that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ has been promoted, which means the stages of child development on their way to adulthood replicate those of our human ancestors on their way to becoming modern humans. This idea has been applied to language acquisition and its evolution, but I’ve never been persuaded. It is intellectually problematic because our human ancestors were never ‘on their way’ to anywhere other than being themselves. My interest in language acquisition is different and twofold. So far as I can determine Ted Hughes never went shopping with Sylvia Plath. He thought her flair for fashion, and her materialistic desires, frivolous. “I need to curb my lust for buying dresses,” she wrote to herself on May 9, 1958 while the married couple were living in Northampton, Massachusetts. Four years later, on her own in London during her last days, she shopped like mad, threw away her country duds, reveled in a new hairdo, and enjoyed wolf whistles on the street. She had repressed a good deal of herself to please the man whose unkempt, often dirty appearance she had schooled herself to tolerate.

So far as I can determine Ted Hughes never went shopping with Sylvia Plath. He thought her flair for fashion, and her materialistic desires, frivolous. “I need to curb my lust for buying dresses,” she wrote to herself on May 9, 1958 while the married couple were living in Northampton, Massachusetts. Four years later, on her own in London during her last days, she shopped like mad, threw away her country duds, reveled in a new hairdo, and enjoyed wolf whistles on the street. She had repressed a good deal of herself to please the man whose unkempt, often dirty appearance she had schooled herself to tolerate. When it comes to gender equality, no society is perfect, but some are widely understood to have come further than others. These societies do a better job of offering equal opportunities, rights and responsibilities, and minimising structural power differences between men and women. One might expect that men and women in these societies would also become more similar to each other in terms of personality and other psychological qualities. Research has previously found differences in men’s and women’s average levels of characteristics such as

When it comes to gender equality, no society is perfect, but some are widely understood to have come further than others. These societies do a better job of offering equal opportunities, rights and responsibilities, and minimising structural power differences between men and women. One might expect that men and women in these societies would also become more similar to each other in terms of personality and other psychological qualities. Research has previously found differences in men’s and women’s average levels of characteristics such as  My apartment has just now been completed. I don’t know which object did it; suddenly everything quietened down and it immediately became inhabited and familiar, as if no longer new—and yet … I would very much like to tell you how everything is, and where and why things are the way they are. Well, there is a small, unremarkable entryway, and a kitchen that will become interesting due only to my daily attempts at cooking (I have to prepare everything myself!); from the entryway you step through a small door and under a dark red curtain of heavy, woven linen (sold at Bernheimer’s in Munich as toile japonaise) into my very large study. There is a huge three-part window partially wedged into a bay as wide as the room itself. To the right of the bay, a glass door leads to a small balcony, while on the left the bay is joined by a blank wall to the wall of the study. Underneath the window there is a broad bench covered with a blue-and-red blanket from Abruzzo(!), and two steps in front of this bench, in the center of the room, is the main desk. There is a second, quite long desk set up as a working table for evening tasks—independent of the window, at an angle in front of the stove, and diagonally blocking the corner. To the left of the large window there hangs a narrow rug with a colorful border that keeps that corner dark, and in front of it stands the yellow samovar on a Russian base, surrounded by some Russian things, images, and holy icons. A very broad chair covered by a good, antique Turkish rug connects (to the left of the wall) to the cupboard for the samovar so that it’s easy to put down one’s glass of tea there. The Turkish blanket is stretched up the wall to the so-called ‘Rubens’—the Adoration of the Magi (oil painting—old, 2 meters long, 47 centimeters high)—and provides the backdrop for the best heirloom: a family crest in a precious silver frame. Then there is a small green table where I have to eat what I cook—and a small sideboard.

My apartment has just now been completed. I don’t know which object did it; suddenly everything quietened down and it immediately became inhabited and familiar, as if no longer new—and yet … I would very much like to tell you how everything is, and where and why things are the way they are. Well, there is a small, unremarkable entryway, and a kitchen that will become interesting due only to my daily attempts at cooking (I have to prepare everything myself!); from the entryway you step through a small door and under a dark red curtain of heavy, woven linen (sold at Bernheimer’s in Munich as toile japonaise) into my very large study. There is a huge three-part window partially wedged into a bay as wide as the room itself. To the right of the bay, a glass door leads to a small balcony, while on the left the bay is joined by a blank wall to the wall of the study. Underneath the window there is a broad bench covered with a blue-and-red blanket from Abruzzo(!), and two steps in front of this bench, in the center of the room, is the main desk. There is a second, quite long desk set up as a working table for evening tasks—independent of the window, at an angle in front of the stove, and diagonally blocking the corner. To the left of the large window there hangs a narrow rug with a colorful border that keeps that corner dark, and in front of it stands the yellow samovar on a Russian base, surrounded by some Russian things, images, and holy icons. A very broad chair covered by a good, antique Turkish rug connects (to the left of the wall) to the cupboard for the samovar so that it’s easy to put down one’s glass of tea there. The Turkish blanket is stretched up the wall to the so-called ‘Rubens’—the Adoration of the Magi (oil painting—old, 2 meters long, 47 centimeters high)—and provides the backdrop for the best heirloom: a family crest in a precious silver frame. Then there is a small green table where I have to eat what I cook—and a small sideboard. T

T Sitting near a window inside Boston’s Four Seasons Hotel, overlooking a duck pond in the city’s Public Garden, Ray Kurzweil held up a sheet of paper showing the steady growth in the amount of raw computer power that a dollar could buy over the last 85 years. A neon-green line rose steadily across the page, climbing like fireworks in the night sky. That diagonal line, he said, showed why humanity was just 20 years away from

Sitting near a window inside Boston’s Four Seasons Hotel, overlooking a duck pond in the city’s Public Garden, Ray Kurzweil held up a sheet of paper showing the steady growth in the amount of raw computer power that a dollar could buy over the last 85 years. A neon-green line rose steadily across the page, climbing like fireworks in the night sky. That diagonal line, he said, showed why humanity was just 20 years away from  There is Orwell the human being. There is Orwell the novelist. There is Orwell the intellectual, the critic, the journalist, the essayist, the radical. But lately, George Orwell—who was born Eric Arthur Blair and who never fully abandoned his original name—has increasingly come to be regarded as a modern oracle, a gifted soothsayer who predicted with terrifying accuracy how fragile and fallible our political systems were, how close the shadow of authoritarianism. His body of work has become a compass to help us navigate our way in times of democratic recession and backsliding, as is the case worldwide. Among all his books, the one that has left the deepest impact on generations of readers across borders is, no doubt, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

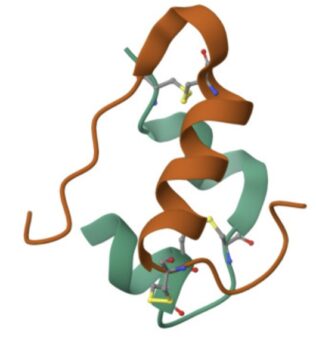

There is Orwell the human being. There is Orwell the novelist. There is Orwell the intellectual, the critic, the journalist, the essayist, the radical. But lately, George Orwell—who was born Eric Arthur Blair and who never fully abandoned his original name—has increasingly come to be regarded as a modern oracle, a gifted soothsayer who predicted with terrifying accuracy how fragile and fallible our political systems were, how close the shadow of authoritarianism. His body of work has become a compass to help us navigate our way in times of democratic recession and backsliding, as is the case worldwide. Among all his books, the one that has left the deepest impact on generations of readers across borders is, no doubt, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Insulin is an abomination. Sure, injecting it saves the lives of millions of diabetics, but that injected protein is unnatural and abhorrent, the product of a genetically modified organism! And it’s not even necessary: Rather than playing God to coax single-celled creatures never designed for insulin production to make the stuff, we could be harvesting it naturally, like we used to just a few decades ago. After all, one need only slaughter about 20,000 pigs or cows to provide a pound of insulin!

Insulin is an abomination. Sure, injecting it saves the lives of millions of diabetics, but that injected protein is unnatural and abhorrent, the product of a genetically modified organism! And it’s not even necessary: Rather than playing God to coax single-celled creatures never designed for insulin production to make the stuff, we could be harvesting it naturally, like we used to just a few decades ago. After all, one need only slaughter about 20,000 pigs or cows to provide a pound of insulin!