Vijaya Ramachandran, Juzel Lloyd, and Seaver Wang at the Breakthrough Journal:

Amongst the many energy-hungry technologies supporting modern society, artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a major driver of energy demand. Data centers—the physical infrastructure enabling AI—are becoming larger, multiplying, and consuming more energy. Environmental organizations such as Greenpeace are concerned that this will jeopardize decarbonization efforts and halt progress in the fight against climate change. AI can track melting icebergs or map deforestation, all the while consuming excessive amounts of carbon-intensive energy. But a closer look at the data shows that fears of AI’s insatiable appetite for energy may be unwarranted.

Amongst the many energy-hungry technologies supporting modern society, artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a major driver of energy demand. Data centers—the physical infrastructure enabling AI—are becoming larger, multiplying, and consuming more energy. Environmental organizations such as Greenpeace are concerned that this will jeopardize decarbonization efforts and halt progress in the fight against climate change. AI can track melting icebergs or map deforestation, all the while consuming excessive amounts of carbon-intensive energy. But a closer look at the data shows that fears of AI’s insatiable appetite for energy may be unwarranted.

If we take reports at face value, we might conclude that AI-induced climate stress is all but inevitable. Niklas Sundberg, a board member of the nonprofit SustainableIT.org claims that a single query on ChatGPT generates 100 times the amount of carbon as a Google search.

More here.

When Henderson got to Yale on the G.I. Bill, he was shocked by the differences between him and his classmates. As he explains in the video above, he learned it was popular for his classmates to hold strong, seemingly progressive views about many of the concerns that shaped his life — drugs, marriage, crime. But they were largely insulated from the consequences of their views. Henderson found that these ideas came to serve as status symbols for the privileged while they, ironically, kept the working class down. He came to call these ideas luxury beliefs.

When Henderson got to Yale on the G.I. Bill, he was shocked by the differences between him and his classmates. As he explains in the video above, he learned it was popular for his classmates to hold strong, seemingly progressive views about many of the concerns that shaped his life — drugs, marriage, crime. But they were largely insulated from the consequences of their views. Henderson found that these ideas came to serve as status symbols for the privileged while they, ironically, kept the working class down. He came to call these ideas luxury beliefs. Alice Munro, considered one of the greatest short-story writers of modern times, was a monster.

Alice Munro, considered one of the greatest short-story writers of modern times, was a monster. O

O D

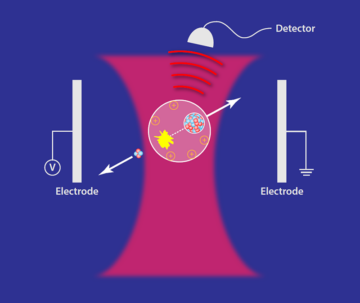

D For centuries, physicists have exploited momentum conservation as a powerful means to analyze dynamical processes, from billiard-ball collisions to galaxy formation to subatomic particle creation in accelerators. David Moore and his research team at Yale University have now put this approach to work in a new setting: they used momentum conservation to determine when a radioactive atom emitted a single helium nucleus, known as an alpha particle (Fig.

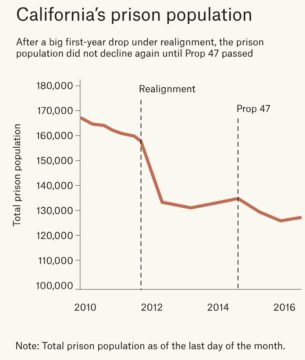

For centuries, physicists have exploited momentum conservation as a powerful means to analyze dynamical processes, from billiard-ball collisions to galaxy formation to subatomic particle creation in accelerators. David Moore and his research team at Yale University have now put this approach to work in a new setting: they used momentum conservation to determine when a radioactive atom emitted a single helium nucleus, known as an alpha particle (Fig.  Asterisk: You’re responsible for managing one of the most comprehensive data sets of criminal outcomes for various criminal justice systems in California. It includes 12 counties and 60% of the state population. How did you put this resource together, and what kinds of outcomes you are tracking with it?

Asterisk: You’re responsible for managing one of the most comprehensive data sets of criminal outcomes for various criminal justice systems in California. It includes 12 counties and 60% of the state population. How did you put this resource together, and what kinds of outcomes you are tracking with it? In 1916 the Bank of England committed what Nikolaus Pevsner was to call the greatest architectural crime to befall London in the 20th century. It decided to demolish much of its own building, designed by the great Georgian neoclassical architect John Soane.

In 1916 the Bank of England committed what Nikolaus Pevsner was to call the greatest architectural crime to befall London in the 20th century. It decided to demolish much of its own building, designed by the great Georgian neoclassical architect John Soane. W

W In recent years, MIT physicist Jeremy England (pictured above) has gained media attention for proposing a thermodynamic energy-dissipation model of the origin of life. England’s view was summarized when he famously said that the origin and evolution of life “should be as unsurprising as rocks rolling downhill.” He continued, “You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant.”1Another physicist, ID theorist Brian Miller, has responded to England’s research.

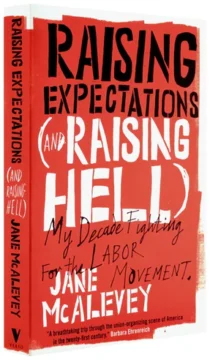

In recent years, MIT physicist Jeremy England (pictured above) has gained media attention for proposing a thermodynamic energy-dissipation model of the origin of life. England’s view was summarized when he famously said that the origin and evolution of life “should be as unsurprising as rocks rolling downhill.” He continued, “You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant.”1Another physicist, ID theorist Brian Miller, has responded to England’s research. Raising Expectations is as much tell-all as organizing manual, but it was Jane’s second book, published in 2016—by an academic press, no less—that turned her into as much of a household name as any labor organizer can be in what she called “the new Gilded Age.”

Raising Expectations is as much tell-all as organizing manual, but it was Jane’s second book, published in 2016—by an academic press, no less—that turned her into as much of a household name as any labor organizer can be in what she called “the new Gilded Age.”

Stephen King, Min Jin Lee, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Bonnie Garmus, Nana Kwame Adjei‑Brenyah, Junot Díaz, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Patterson, Elin Hilderbrand, Annette Gordon‑Reed, Rebecca Roanhorse, Marlon James, Roxane Gay, Jonathan Lethem, Sarah MacLean, Ed Yong, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Paul Tremblay, Nick Hornby, Scott Turow, Daniel Alarcón, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Lucy Sante, Gary Shteyngart, Anand Giridharadas, Jessamine Chan, Michael Robbins, Alma Katsu, Megan Abbott, Joshua Ferris, Ann Napolitano, John Irving, Tiya Miles, Jami Attenberg, Stephen L. Carter, Sarah Schulman, Elizabeth Hand, Dion Graham, Jeremy Denk, Morgan Jerkins, Michael Roth & Ryan Holiday.

Stephen King, Min Jin Lee, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Bonnie Garmus, Nana Kwame Adjei‑Brenyah, Junot Díaz, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Patterson, Elin Hilderbrand, Annette Gordon‑Reed, Rebecca Roanhorse, Marlon James, Roxane Gay, Jonathan Lethem, Sarah MacLean, Ed Yong, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Paul Tremblay, Nick Hornby, Scott Turow, Daniel Alarcón, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Lucy Sante, Gary Shteyngart, Anand Giridharadas, Jessamine Chan, Michael Robbins, Alma Katsu, Megan Abbott, Joshua Ferris, Ann Napolitano, John Irving, Tiya Miles, Jami Attenberg, Stephen L. Carter, Sarah Schulman, Elizabeth Hand, Dion Graham, Jeremy Denk, Morgan Jerkins, Michael Roth & Ryan Holiday. Over several years now, a single question has refused to leave me: what is beauty? Triggering it was a series of aesthetic experiences so intense that I count them among the most significant moments of my life. They felt supercharged with meaning, yet what they meant I could not tell. After a couple years of scratching my head, I still cannot claim to understand them. Nevertheless, I believe I have taken a step towards understanding what beauty is.

Over several years now, a single question has refused to leave me: what is beauty? Triggering it was a series of aesthetic experiences so intense that I count them among the most significant moments of my life. They felt supercharged with meaning, yet what they meant I could not tell. After a couple years of scratching my head, I still cannot claim to understand them. Nevertheless, I believe I have taken a step towards understanding what beauty is.