Claudia Roth Pierpont at The New Yorker:

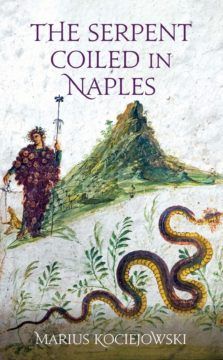

One day a few years ago, an Englishman walked into a tourist shop on the ground floor of a Neapolitan palazzo and told a woman he encountered there that he was searching for the soul of Naples. The building, named Palazzo del Panormita, for an obscure fifteenth-century author of erotic Latin epigrams, stands near a small piazza named for the River Nile, recalling the Egyptian traders who once lived in a mini-quarter within the city center’s ancient Greek grid. (There was a Greek settlement there before the Parthenon was built.) Today, that grid runs into a thoroughfare cut by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, when the Kingdom of Naples was under their imperial control. Named Via Toledo by the Spanish, the street became Via Roma three centuries later, when Naples, at last free of a series of foreign overlords, joined a unified Italy. And yet for many Neapolitans the idea of being governed from Rome was apparently as abhorrent as Spanish dominion: the name Via Roma aroused so much resentment that, in the nineteen-eighties, the city brought the old Spanish name back into official use. Even now, Neapolitans differ sharply on what their central commercial street should be called.

One day a few years ago, an Englishman walked into a tourist shop on the ground floor of a Neapolitan palazzo and told a woman he encountered there that he was searching for the soul of Naples. The building, named Palazzo del Panormita, for an obscure fifteenth-century author of erotic Latin epigrams, stands near a small piazza named for the River Nile, recalling the Egyptian traders who once lived in a mini-quarter within the city center’s ancient Greek grid. (There was a Greek settlement there before the Parthenon was built.) Today, that grid runs into a thoroughfare cut by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, when the Kingdom of Naples was under their imperial control. Named Via Toledo by the Spanish, the street became Via Roma three centuries later, when Naples, at last free of a series of foreign overlords, joined a unified Italy. And yet for many Neapolitans the idea of being governed from Rome was apparently as abhorrent as Spanish dominion: the name Via Roma aroused so much resentment that, in the nineteen-eighties, the city brought the old Spanish name back into official use. Even now, Neapolitans differ sharply on what their central commercial street should be called.

more here.

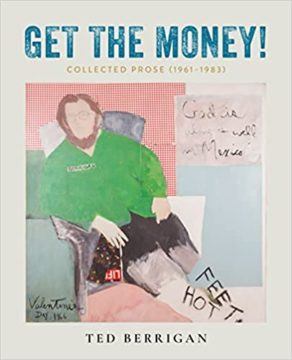

Though there is less of Berrigan’s prose than his poetry, the best of it—his early journals, the collaged “interview” with

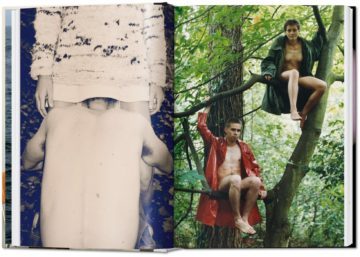

Though there is less of Berrigan’s prose than his poetry, the best of it—his early journals, the collaged “interview” with  Over the course of his 36-year career, the photographer

Over the course of his 36-year career, the photographer  In October 2021, Meta Platforms, Inc, released a “trailer”, hosted by the company’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, to give a visual tour of its recent expansion into the Metaverse – the immersive, virtual-reality world that is expected to be the next great iteration of our internet technologies.

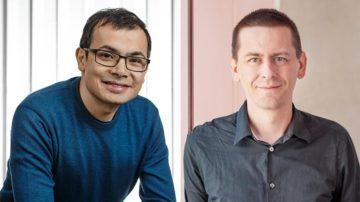

In October 2021, Meta Platforms, Inc, released a “trailer”, hosted by the company’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, to give a visual tour of its recent expansion into the Metaverse – the immersive, virtual-reality world that is expected to be the next great iteration of our internet technologies. The researchers behind the AlphaFold artificial-intelligence (AI) system have won one of this year’s US$3-million Breakthrough prizes — the most lucrative awards in science. Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, both at DeepMind in London, were recognized for creating the tool that has predicted the 3D structures of almost every known protein on the planet.

The researchers behind the AlphaFold artificial-intelligence (AI) system have won one of this year’s US$3-million Breakthrough prizes — the most lucrative awards in science. Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, both at DeepMind in London, were recognized for creating the tool that has predicted the 3D structures of almost every known protein on the planet. Switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy could save the world as much as $12tn (£10.2tn) by 2050, an Oxford University study says.

Switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy could save the world as much as $12tn (£10.2tn) by 2050, an Oxford University study says. “She has her mother’s eyes,” begins the advertisement, “but will she also inherit her breast cancer diagnosis?” The smooth voice in the video is promoting the services of Genomic Prediction, a US company that says it can help prospective parents to answer this question by testing the genetics of embryos during fertility treatment. For Nathan Treff, the company’s chief scientific officer, this mission is personal. At 24, he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes — a disease that cost his grandfather his leg. If Treff had it his way, no child would be born with a high risk for the condition.

“She has her mother’s eyes,” begins the advertisement, “but will she also inherit her breast cancer diagnosis?” The smooth voice in the video is promoting the services of Genomic Prediction, a US company that says it can help prospective parents to answer this question by testing the genetics of embryos during fertility treatment. For Nathan Treff, the company’s chief scientific officer, this mission is personal. At 24, he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes — a disease that cost his grandfather his leg. If Treff had it his way, no child would be born with a high risk for the condition. Mayor of New York City is famously a dead-end job. The last New York mayor to win higher office was John T. Hoffman, and that was in 1868. He became governor. Every mayor since then has found the way up barred. And, for some, the way up turned into the way down.

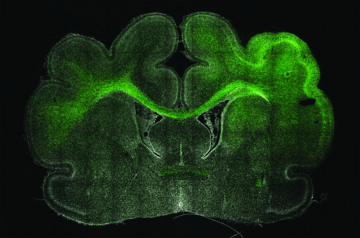

Mayor of New York City is famously a dead-end job. The last New York mayor to win higher office was John T. Hoffman, and that was in 1868. He became governor. Every mayor since then has found the way up barred. And, for some, the way up turned into the way down. We humans are proud of our big brains, which are responsible for our ability to plan ahead, communicate, and create. Inside our skulls, we pack, on average, 86 billion neurons—up to three times more than those of our primate cousins. For years, researchers have tried to figure out how we manage to develop so many brain cells. Now, they’ve come a step closer: A new study shows a single amino acid change in a metabolic gene helps our brains develop more neurons than other mammals—and more than our extinct cousins, the Neanderthals.

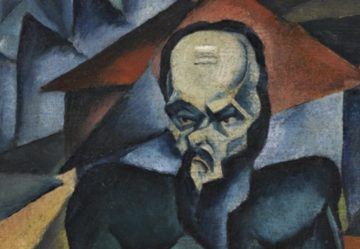

We humans are proud of our big brains, which are responsible for our ability to plan ahead, communicate, and create. Inside our skulls, we pack, on average, 86 billion neurons—up to three times more than those of our primate cousins. For years, researchers have tried to figure out how we manage to develop so many brain cells. Now, they’ve come a step closer: A new study shows a single amino acid change in a metabolic gene helps our brains develop more neurons than other mammals—and more than our extinct cousins, the Neanderthals. Kevin Birmingham prefaces his account of the tortured progress of the writing of Crime and Punishment with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s terse summation of his novel’s plot: “There’s an evil spirit here.” It’s a statement Birmingham invites us to ponder throughout his masterly book. Can we be disturbed but not necessarily repulsed by the actions of a particularly heinous criminal? Might such a character actually engage our sympathies? In The Sinner and the Saint, Birmingham sets himself the task of revealing the soul of an author, shattered and nearly sunk by the cumulative blows of life, struggling to get close to a murderer’s mind—and he succeeds brilliantly.

Kevin Birmingham prefaces his account of the tortured progress of the writing of Crime and Punishment with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s terse summation of his novel’s plot: “There’s an evil spirit here.” It’s a statement Birmingham invites us to ponder throughout his masterly book. Can we be disturbed but not necessarily repulsed by the actions of a particularly heinous criminal? Might such a character actually engage our sympathies? In The Sinner and the Saint, Birmingham sets himself the task of revealing the soul of an author, shattered and nearly sunk by the cumulative blows of life, struggling to get close to a murderer’s mind—and he succeeds brilliantly. THOUGH I DIDN’T CRY FOR BOWIE, I cried for Issey the way I cried for Leonard Cohen. My best friend wore Issey’s perfume, which bottled the sensation of water on skin. I have a few of his Pleats Please garments, harvested from eBay, and there is a thrifted, asymmetrical, gray ribbed heavy wool pullover sweater that I still regret giving away. It was from the early ’80s, like the raw silk, pleated madder-red smock I still treasure for its color and drape. His garments tend to stay with you. My ninety-six-year-old Parisian mother-in-law recalls an Issey jacket she bought decades ago. It was a green wool—the color of a traveling cloak, she says—unlined, light but warm, with a quality she describes as enveloping, raising her hands as she says this as if to grasp a generous collar to shelter her neck and face against a piercing wind, or an unwelcome glance. This feeling of envelopment, both calming and freeing, is at the heart of Issey Miyake’s oeuvre. You experience the garment as shelter at the same time as its interiority liberates an emotional and expressive pleasure. My mother-in-law’s gestural enactment of her remembered Issey jacket defines the designer’s paradoxical lyricism. His garments wrap you in lightness. There is a kind of phantom smock hidden in everything he made.

THOUGH I DIDN’T CRY FOR BOWIE, I cried for Issey the way I cried for Leonard Cohen. My best friend wore Issey’s perfume, which bottled the sensation of water on skin. I have a few of his Pleats Please garments, harvested from eBay, and there is a thrifted, asymmetrical, gray ribbed heavy wool pullover sweater that I still regret giving away. It was from the early ’80s, like the raw silk, pleated madder-red smock I still treasure for its color and drape. His garments tend to stay with you. My ninety-six-year-old Parisian mother-in-law recalls an Issey jacket she bought decades ago. It was a green wool—the color of a traveling cloak, she says—unlined, light but warm, with a quality she describes as enveloping, raising her hands as she says this as if to grasp a generous collar to shelter her neck and face against a piercing wind, or an unwelcome glance. This feeling of envelopment, both calming and freeing, is at the heart of Issey Miyake’s oeuvre. You experience the garment as shelter at the same time as its interiority liberates an emotional and expressive pleasure. My mother-in-law’s gestural enactment of her remembered Issey jacket defines the designer’s paradoxical lyricism. His garments wrap you in lightness. There is a kind of phantom smock hidden in everything he made. Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy.

Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy. Scientists say they have slowed and even reversed some of the devastating and relentless decline caused by motor-neurone disease (MND). The treatment works in only 2% of patients but has been described as “truly remarkable” and a “real moment of hope” for the whole disease. One leading expert said it was the first time she had seen patients improve – but this is not a cure. The MND Association said there was “mounting confidence” in the therapy. MND, also known as amyotrophic-lateral sclerosis (ALS), is caused by the death of the nerves that carry messages from the brain to people’s muscles. It affects their ability to move, talk and even breathe. The disease dramatically shortens people’s lives and most die within two years of being diagnosed.

Scientists say they have slowed and even reversed some of the devastating and relentless decline caused by motor-neurone disease (MND). The treatment works in only 2% of patients but has been described as “truly remarkable” and a “real moment of hope” for the whole disease. One leading expert said it was the first time she had seen patients improve – but this is not a cure. The MND Association said there was “mounting confidence” in the therapy. MND, also known as amyotrophic-lateral sclerosis (ALS), is caused by the death of the nerves that carry messages from the brain to people’s muscles. It affects their ability to move, talk and even breathe. The disease dramatically shortens people’s lives and most die within two years of being diagnosed.