Tomiwa Owolade in The Ideas Letter:

I am not from New York. I am not Jewish. I am not a member of a Marxist group. I did not live through the 1930s and 1940s. I am a 27-year-old British-Nigerian who grew up in London. Yet the New York Intellectuals are my people.

They are my people because even though they had ample reason to be defined by their identity, they tried to transcend their personal circumstances with their wide-ranging embrace of culture. They didn’t see themselves, and they should not be seen, simply as Jewish New Yorkers who were advocating anti-fascism and anti-Stalinism in the middle of the 20th century; they possessed a universalist spirit. And this is a spirit to which I aspire.

I remember the wonder I felt reading my first James Baldwin essays from his 1955 collection Notes of a Native Son at my university library or watching I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s excellent documentary about Baldwin, on a bright spring afternoon of 2017. I remember in my early 20s picking up Elizabeth Hardwick’s fat collection of criticism (published by NYRB Classics) in a second-hand bookshop and devouring it. I remember discovering the lives and works of other New York Intellectuals in Louis Menand’s monumental 2021 cultural history The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War.

More here. Relatedly, Leonard Benardo in The New Statesman:

For many years my mother taught a course on women in literature in a public high school in the Bronx, New York. In the first half of the semester, she selected texts by men writing about women. The second half, books penned by women about women. Hers was a pedagogical conceit that fostered lively discussion among engaged teenagers as to how men and women write differently about the female experience.

Write Like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals is historian Ronnie Grinberg’s variation on my mother’s theme. Grinberg wants to know how the writing of a legendary band of essayists and critics, dubbed the New York Intellectuals by one of its members, reflects what she calls a “secular Jewish masculinity”. Grinberg is especially focused on how the few women writers of the circle were engulfed by a masculine milieu, a trope that recurs in her book like a Wagnerian leitmotif. Did “secular Jewish masculinity” toughen the prose of (and establish a pose for) the New York Intellectuals? What exactly does it mean to “write like a man”, and is it a useful frame to reassess the criticism of this hallowed group?

The New York Intellectuals are customarily associated with that cohort of striving first-generation Jews who met in New York’s great public university, City College of New York (CCNY), and forged comradeships through the impassioned contestation of ideas. From the 1930s through the 1980s, by means of small journals with outsized influence – Partisan Review, Commentary, Encounter – this loosely fitted imagined community produced some of the most incisive and bold American writing of the 20th century. Arguing the World, Joseph Dorman’s documentary from 1997, which traced the intellectual life trajectories of four of its members, Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Irving Howe and Nathan Glazer, is the consummate statement of their original convictions and different roads taken. Predominantly male, white and Jewish, there were still others in the polymathic cauldron of the New York Intellectuals who were not: Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Hardwick and Dwight Macdonald. What held such a complicated group together and over generations? In a word, ideas. Ideas were the currency, and politics and culture the canvas, upon which the American world of letters took a great leap forward.

I

I The case was the stuff of tabloid dreams. It had everything: murder, blackmail, money, class, secrets, even the occult. And the public, in the time of Prohibition, anti-vice crusades and so-called purity campaigns to combat germs, couldn’t get enough of it.

The case was the stuff of tabloid dreams. It had everything: murder, blackmail, money, class, secrets, even the occult. And the public, in the time of Prohibition, anti-vice crusades and so-called purity campaigns to combat germs, couldn’t get enough of it. Imagine if after Oppenheimer successfully detonated the first atomic bomb, the rest of the world had just shrugged its shoulders and carried on as normal.

Imagine if after Oppenheimer successfully detonated the first atomic bomb, the rest of the world had just shrugged its shoulders and carried on as normal. For good and valid reasons, most of the United States has moved away from having electricity generated, transmitted and delivered by monopolies. The reasons for the change did not primarily have to do with nuclear energy. But a nuclear renaissance could turn out to be a casualty. The old model made construction of a new power plant a shared risk; the new one, in most of the country, turns building a generator into a speculative investment.

For good and valid reasons, most of the United States has moved away from having electricity generated, transmitted and delivered by monopolies. The reasons for the change did not primarily have to do with nuclear energy. But a nuclear renaissance could turn out to be a casualty. The old model made construction of a new power plant a shared risk; the new one, in most of the country, turns building a generator into a speculative investment. The Red Planet has long captured human imagination, going at least as far back as the ancient Greeks, who designated it the god of war. In the modern era, once it was understood that Mars was another planet in our system that could be seen through telescopes, it became romanticized by astronomers like Giovanni Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell, generating dreams of canals and life and civilizations — dreams later disappointed by instruments showing it to be apparently lifeless and desiccated.

The Red Planet has long captured human imagination, going at least as far back as the ancient Greeks, who designated it the god of war. In the modern era, once it was understood that Mars was another planet in our system that could be seen through telescopes, it became romanticized by astronomers like Giovanni Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell, generating dreams of canals and life and civilizations — dreams later disappointed by instruments showing it to be apparently lifeless and desiccated. Seven of the following ten books have something to do with the Covid pandemic 2019–22, and the remaining three address some of the other traumas that consume our politics, and planet, during these troubled times. “Aren’t you worried?” a character in Hari Kunzru’s novel Blue Ruin asks, “I mean, about the future?” It’s a question many of us are asking.

Seven of the following ten books have something to do with the Covid pandemic 2019–22, and the remaining three address some of the other traumas that consume our politics, and planet, during these troubled times. “Aren’t you worried?” a character in Hari Kunzru’s novel Blue Ruin asks, “I mean, about the future?” It’s a question many of us are asking. To have a child, it is often said, is to transform one’s identity. What this might have meant in the past is more or less obvious: With few exceptions, for the better part of history, to have a child meant it was time for a woman to say her final farewells to whatever public existence she managed to forge up to that point. But now there is another, more mysterious change that becoming a mother is understood to imply, more basic than the historical conditions of oppression. This change is supposed to reconfigure the deepest core of one’s being. When the contemporary analytic philosopher L. A. Paul wanted to introduce the idea of a fundamentally transformative experience, one of her central examples was having a child. For women, especially, becoming a parent is frequently described as a total revolution of the self. “Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your ‘I’ goes with,” philosopher Agnes Callard

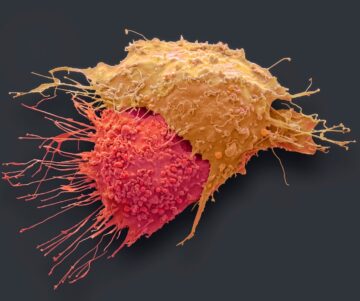

To have a child, it is often said, is to transform one’s identity. What this might have meant in the past is more or less obvious: With few exceptions, for the better part of history, to have a child meant it was time for a woman to say her final farewells to whatever public existence she managed to forge up to that point. But now there is another, more mysterious change that becoming a mother is understood to imply, more basic than the historical conditions of oppression. This change is supposed to reconfigure the deepest core of one’s being. When the contemporary analytic philosopher L. A. Paul wanted to introduce the idea of a fundamentally transformative experience, one of her central examples was having a child. For women, especially, becoming a parent is frequently described as a total revolution of the self. “Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your ‘I’ goes with,” philosopher Agnes Callard  Every year, cancer kills approximately 10 million people worldwide. Of those who die, two thirds do so because they were diagnosed with advanced disease. A new paradigm in the approach to cancer is overdue. COVID-19 has already altered conversations and expectations within the medical community and is forcing a rethinking of many public health issues.

Every year, cancer kills approximately 10 million people worldwide. Of those who die, two thirds do so because they were diagnosed with advanced disease. A new paradigm in the approach to cancer is overdue. COVID-19 has already altered conversations and expectations within the medical community and is forcing a rethinking of many public health issues. Dear Reader,

Dear Reader, What happens to the job market when the government raises the minimum wage? For decades, higher education in the United States has taught economics students to answer this question by reasoning from first principles. When the price of something rises, people tend to buy less of it. Therefore, if the price of labour rises, businesses will choose to ‘buy’ less of it – meaning they’ll hire fewer people. Students learn that a higher minimum wage means fewer jobs.

What happens to the job market when the government raises the minimum wage? For decades, higher education in the United States has taught economics students to answer this question by reasoning from first principles. When the price of something rises, people tend to buy less of it. Therefore, if the price of labour rises, businesses will choose to ‘buy’ less of it – meaning they’ll hire fewer people. Students learn that a higher minimum wage means fewer jobs. When it comes to protecting animal species, you would think that conservation biologists, environmental advocates, and animal-loving members of the public are all on the same page. However, in Why Sharks Matter, marine biologist David Shiffman shows that this is not always the case. Though there are plenty of books marvelling at sharks, this, to my knowledge, is the first one to provide an informed and informative look at shark conservation. Frank, frequently opinionated, and full of refreshingly counterintuitive ideas, Why Sharks Matter is an eye-opener that delivered far more than I expected based on the title.

When it comes to protecting animal species, you would think that conservation biologists, environmental advocates, and animal-loving members of the public are all on the same page. However, in Why Sharks Matter, marine biologist David Shiffman shows that this is not always the case. Though there are plenty of books marvelling at sharks, this, to my knowledge, is the first one to provide an informed and informative look at shark conservation. Frank, frequently opinionated, and full of refreshingly counterintuitive ideas, Why Sharks Matter is an eye-opener that delivered far more than I expected based on the title. Michoacán, where about four in five of all avocados

Michoacán, where about four in five of all avocados