Zero Gravity

You leave Earth looking for perspective.

How you long to see it, the blue marble,

from outer space. The overview

changes everything astronauts say

and you are looking for change,

to not take life so seriously. So much

energy required to get off the planet to

break with gravity, the bond with Earth,

the ship violent with propulsion’s inferno

shaking you loose from the known world.

But maybe your friend is right, maybe Earth’s best

hope is mass conversions to religions that

teach reincarnation, then people might care

about the future of the planet? You unbuckle,

let yourself float free, wanting the thrill

before this once-in-a-lifetime trip ends,

even a few minutes of giddy weightlessness

so close to death, a tangible peril right

outside the window, Earth passing there

below you now, alone in the darkness.

by Sally Ashton

from The Ecotheo Review

Desaire and her colleagues first described their ChatGPT detector in June, when they applied it to Perspective articles from the journal Science

Desaire and her colleagues first described their ChatGPT detector in June, when they applied it to Perspective articles from the journal Science There is an outdated idea that science and art are polar opposites. That science, associated with the left brain hemisphere, is logical, structured, whereas art, the domain of the right hemisphere is soft, intuitive, creative, guided by practiced judgement and innate skill. Of course, any neuro-scientist will tell you that the distinction between “right and left brain thinking” is a myth, that both sides are equally important in thinking through a math problem and painting a picture.

There is an outdated idea that science and art are polar opposites. That science, associated with the left brain hemisphere, is logical, structured, whereas art, the domain of the right hemisphere is soft, intuitive, creative, guided by practiced judgement and innate skill. Of course, any neuro-scientist will tell you that the distinction between “right and left brain thinking” is a myth, that both sides are equally important in thinking through a math problem and painting a picture. These are good times to be a thinking, conscious creature, despite events in the world that might make us doubt that. These are even better times to be a creature who thinks about consciousness: the scientific debate is livelier than ever, and technological advances and political controversies are making the practical and philosophical questions surrounding consciousness ever more pressing. Will artificial intelligence (AI) become conscious? (Or maybe it already is…? Well, no, I would say, but we’ll get to that later.) Can state-of-the-art algorithms manipulate our consciousness to change our view of the world? Which animals, besides humans, are conscious? What about fetuses? Or artificial neural organoids?

These are good times to be a thinking, conscious creature, despite events in the world that might make us doubt that. These are even better times to be a creature who thinks about consciousness: the scientific debate is livelier than ever, and technological advances and political controversies are making the practical and philosophical questions surrounding consciousness ever more pressing. Will artificial intelligence (AI) become conscious? (Or maybe it already is…? Well, no, I would say, but we’ll get to that later.) Can state-of-the-art algorithms manipulate our consciousness to change our view of the world? Which animals, besides humans, are conscious? What about fetuses? Or artificial neural organoids? A “Theory of Everything” is physicists’ somewhat tongue-in-cheek phrase for a hypothetical model of all the fundamental physical interactions. Of course, even if we had such a theory, it would tell us nothing new about higher-level emergent phenomena, all the way up to human behavior and society. Can we even imagine a “Theory of Everyone,” providing basic organizing principles for society? Michael Muthukrishna believes we can, and indeed that we can see the outlines of such a theory emerging, based on the relationships of people to each other and to the physical resources available.

A “Theory of Everything” is physicists’ somewhat tongue-in-cheek phrase for a hypothetical model of all the fundamental physical interactions. Of course, even if we had such a theory, it would tell us nothing new about higher-level emergent phenomena, all the way up to human behavior and society. Can we even imagine a “Theory of Everyone,” providing basic organizing principles for society? Michael Muthukrishna believes we can, and indeed that we can see the outlines of such a theory emerging, based on the relationships of people to each other and to the physical resources available. In a cat’s world, where smells are paramount, it must be a bewildering experience when they first hear a person speak. So many different, unfamiliar sounds directed either at another person or, even more perplexingly, at the cat. Humans are very preoccupied with the spoken word, babbling away at everyone and everything we meet. Intrigued as to what their “spoken” sounds mean, we have developed something of a fascination with the vocalizations of cats too. Nestled deep in the history books, a diary entry by the Abbé Galiani of Naples, dated March 21, 1772, offers some of the earliest recorded insights into cat vocalizations.

In a cat’s world, where smells are paramount, it must be a bewildering experience when they first hear a person speak. So many different, unfamiliar sounds directed either at another person or, even more perplexingly, at the cat. Humans are very preoccupied with the spoken word, babbling away at everyone and everything we meet. Intrigued as to what their “spoken” sounds mean, we have developed something of a fascination with the vocalizations of cats too. Nestled deep in the history books, a diary entry by the Abbé Galiani of Naples, dated March 21, 1772, offers some of the earliest recorded insights into cat vocalizations. After Betty Friedan got her Smith College classmates to complete a questionnaire about their lives at their 15th reunion in 1957, she immediately grasped the significance of their responses. Many of the highly educated women felt trapped by midcentury America’s constrictive domestic ideals, unfulfilled by the roles of housewife and mother. Friedan, a freelance writer and a wife and mother herself, was unable to interest any magazines in publishing her findings. She instead embarked on writing “The Feminine Mystique,” the explosive and groundbreaking book whose 1963 publication turned its author into a celebrity and, more significantly, is credited with igniting the second wave of the feminist movement.

After Betty Friedan got her Smith College classmates to complete a questionnaire about their lives at their 15th reunion in 1957, she immediately grasped the significance of their responses. Many of the highly educated women felt trapped by midcentury America’s constrictive domestic ideals, unfulfilled by the roles of housewife and mother. Friedan, a freelance writer and a wife and mother herself, was unable to interest any magazines in publishing her findings. She instead embarked on writing “The Feminine Mystique,” the explosive and groundbreaking book whose 1963 publication turned its author into a celebrity and, more significantly, is credited with igniting the second wave of the feminist movement. For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of

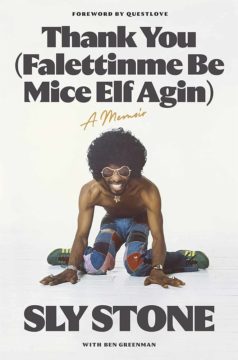

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of  One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.”

One thing that remains intact for Stone at age 80 is the sense of wordplay and fun-house language that distinguished his lyrics (read the song/book title out loud), and some of the biggest pleasures in “Thank You” come when we witness him teasing out a theme. His response to other people telling his story and analyzing his struggles: “They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. … It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.” Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like.

Spanning from 625 BCE to 476 CE, the Roman Empire is still one of the most iconic of all time. At their highest, the Romans conquered Britain, Italy, much of the Middle East, the North African coast, Greece, Spain, and, of course, Italy. From their inventions to their way of life, Ancient Rome was one of the most influential cultures the planet has ever seen. Being the first city to have over 1 million people is just one of the things the time period has to its name, leading many to wonder what life in Rome was really like. The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other.

The first common argument for group minds is the argument from equivalence. I.e., a neuron is a very efficient and elegant way to transmit information. But one can transmit information with all sorts of things. There’s nothing supernatural about neurons. So could not an individual ant act much like a single neuron in an ant colony? And if you find it impossible to believe that an ant colony might be conscious, that it couldn’t emerge from pheromone trails and the collective little internal decisions of ants—if you find the idea of a conscious smell ridiculous—you have to then imagine opening up a human’s head and zooming in to neurons firing their action potentials, and explain why the same skepticism wouldn’t apply to our little cells that just puff vesicles filled with molecules at each other. Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle.

Who knows how many times I stood before Carracci’s Venus, Adonis and Cupid without noticing a crucial detail, a tiny mark that holds as in a cipher the meaning of the tale. Perhaps I had not looked as closely as I thought. “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” George Orwell’s remark about our observation of reality can be applied as well to works of art. Until recently, I had never noticed the speck of a red dot on Venus’ golden, shining skin, just on the edge of the small patch of shadow between her breasts, as if a pinprick had left behind a tiny trace of blood. I failed to see it even though the figure of Cupid was pointing from within the painting to where I should look. The picture itself discloses the key to decoding its riddle.