Zain Khalid at Bookforum:

KARL KRAUS WROTE THAT EVERYTHING FITS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE. Maybe. Maybe everything in an artist’s corpus, no matter how incongruous, reflects, repeats, rhymes. Yet this is not the case for Percival Everett. No thematic or formal schema is suitable. He climbs the stairs sideways. His patently ridiculous conceits seem like challenges to his own mischievousness, bids to marry his uniquely sweeping curiosities to a bardic impulse. Charmingly, he’d never admit as much. “I know nothing,” he said in a recent New Yorker profile. “I’m just a dumb old cowboy.” Sure. It remains a considerable feat for Everett to have remained eccentric in the increasingly rational and prefabricated business of literature. He has his prevailing modes—racial satires, Westerns, crime procedurals, retellings of ancient myths, despondent autobiographical metafiction—but all of them are in flux, appearing in different admixtures. It’s hard to imagine another author pulling off, or even attempting, Glyph (1999),a novel about a toddler with a farcically high IQ; in Everett’s hands, the gambit is hilarious, bone-dry, and tragic. Erasure (2001), a canny parody of writers and racial fetishization, is even more affecting as a portrait of senescence. I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), a hysterical abuse of Ted Turner, the media, and various social structures, is also a repudiation of Everett’s previous work. (About Erasure, the author-character, Percival Everett, remarks, “I didn’t like writing it, and I didn’t like it when I was done with it.”) To apply superficial categories is to miss the point; Everett understands that each person is witness to a series of absurd debacles, and his fiction poses the question: What, if anything, is there to be made of our continued looking?

KARL KRAUS WROTE THAT EVERYTHING FITS WITH EVERYTHING ELSE. Maybe. Maybe everything in an artist’s corpus, no matter how incongruous, reflects, repeats, rhymes. Yet this is not the case for Percival Everett. No thematic or formal schema is suitable. He climbs the stairs sideways. His patently ridiculous conceits seem like challenges to his own mischievousness, bids to marry his uniquely sweeping curiosities to a bardic impulse. Charmingly, he’d never admit as much. “I know nothing,” he said in a recent New Yorker profile. “I’m just a dumb old cowboy.” Sure. It remains a considerable feat for Everett to have remained eccentric in the increasingly rational and prefabricated business of literature. He has his prevailing modes—racial satires, Westerns, crime procedurals, retellings of ancient myths, despondent autobiographical metafiction—but all of them are in flux, appearing in different admixtures. It’s hard to imagine another author pulling off, or even attempting, Glyph (1999),a novel about a toddler with a farcically high IQ; in Everett’s hands, the gambit is hilarious, bone-dry, and tragic. Erasure (2001), a canny parody of writers and racial fetishization, is even more affecting as a portrait of senescence. I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), a hysterical abuse of Ted Turner, the media, and various social structures, is also a repudiation of Everett’s previous work. (About Erasure, the author-character, Percival Everett, remarks, “I didn’t like writing it, and I didn’t like it when I was done with it.”) To apply superficial categories is to miss the point; Everett understands that each person is witness to a series of absurd debacles, and his fiction poses the question: What, if anything, is there to be made of our continued looking?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

O

O I

I Robinson opens

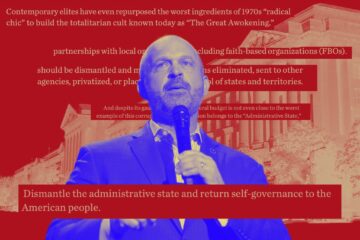

Robinson opens  The week after taking office in 2017, Donald Trump announced his administration’s signature policy on the administrative state—the constellation of agencies, institutions, and procedures that Congress has created to help the president implement the laws it passes—when he

The week after taking office in 2017, Donald Trump announced his administration’s signature policy on the administrative state—the constellation of agencies, institutions, and procedures that Congress has created to help the president implement the laws it passes—when he  Before the automobile, cities were powered by horses. These urban equines ferried passengers in streetcars and carriages; they pulled fire engines and ambulances. They delivered everything from milk and ice to mail. They hauled the coal for locomotive and steam engines.

Before the automobile, cities were powered by horses. These urban equines ferried passengers in streetcars and carriages; they pulled fire engines and ambulances. They delivered everything from milk and ice to mail. They hauled the coal for locomotive and steam engines. I

I What kind of world is this? That’s the question prompted over and over by Joseph O’Neill’s new novel

What kind of world is this? That’s the question prompted over and over by Joseph O’Neill’s new novel