by Rafaël Newman

In June 1932, half a year before Adolf Hitler was sworn in as German Chancellor, Victor Klemperer watched Nazis on a newsreel marching through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. A professor of Romance languages at the Technical University of Dresden, whose area of specialization was the 18th century and the French Enlightenment, Klemperer (1881-1960) was unpleasantly gripped by this first encounter with what he termed “fanaticism in its specifically National Socialist form,” and by the “expression of religious ecstasy” he discerned in the eyes of a young spectator as the drum major passed by, balanced precariously on goose-stepping legs while he robotically beat time.

In June 1932, half a year before Adolf Hitler was sworn in as German Chancellor, Victor Klemperer watched Nazis on a newsreel marching through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. A professor of Romance languages at the Technical University of Dresden, whose area of specialization was the 18th century and the French Enlightenment, Klemperer (1881-1960) was unpleasantly gripped by this first encounter with what he termed “fanaticism in its specifically National Socialist form,” and by the “expression of religious ecstasy” he discerned in the eyes of a young spectator as the drum major passed by, balanced precariously on goose-stepping legs while he robotically beat time.

This initial morbid fascination—with National Socialist martial aesthetics, and eventually with Nazi ideology as expressed linguistically—was to prove a lifesaver after 1933 when Klemperer, although a convert to Christianity, was systematically deprived of his academic privileges, and then of his civil rights, by the Nazis now in power, who regarded him as an unalterably “biological” Jew. Klemperer’s marriage to an “Aryan” woman saved him from the deadly fate reserved for millions of others, but he nevertheless suffered as a form of torture his exclusion from libraries, his confinement with his wife to a Judenhaus, and the mindless industrial work he was forced to perform:

In my hours of revulsion and hopelessness, during the endless drudgery of sheerly mechanical factory labor, by the side of the sick and dying, at gravesites, when I myself was in distress, at moments of the greatest agony, as my heart was failing in my body—the demand I made of myself came faithfully to my aid: to observe, to study, to remember what has occurred—tomorrow things will look different again, tomorrow you will feel different again; set down the way this moment announces itself, record its impact. And very soon, this call to elevate myself above the situation and to preserve my inner liberty had been condensed into a secret formula, one with reliable effect: LTI, LTI!

“LTI,” Klemperer’s “secret formula,” was his shorthand for the project that sustained him: documenting the language used by the National Socialists as they gradually exerted totalitarian control over German minds (and “non-German” bodies). “LTI” stands for Lingua Tertii Imperii, Klemperer’s own taxonomy for “The Language of the Third Reich”.

The neo-Latin formulation paid tribute to the philologist’s training in Romance languages at the same time as it parodied the petty bourgeois puffery of the Nazis, while its abbreviation—LTI—lampooned the German fascists’ tendency to produce mystifying bureaucratic initialisms (BDM, HJ, NSDAP…). Klemperer had kept a diary since the age of 16 and he continued the practice, if under increasingly straitened circumstances, during the period of Hitler’s reign, from 1933 to 1945. His notes in those diaries on language under the Nazis then served him after the fall of the Reich as the basis for LTI: Notizbuch eines Philologen (1947), published in what was soon to become the German Democratic Republic (DDR), where Klemperer regained his academic career and played a role as parliamentarian until shortly before his death in 1960.

In a series of 36 mordant, academically precise essays, occasionally apologizing to the reader for his presumed pedantry, Klemperer brilliantly exposes the deep (or rather, shallow) structure of Nazi language, which he maintains provides a precise map of National Socialist thought, such as it was. Like a dire forerunner of Mythologies, Roland Barthes’s celebrated study of the clichés subtending the French imaginary, LTI sensuously evokes the atmosphere of its cultural moment even as it subjects that culture to critical analysis. Klemperer notes in his introduction that the 1947 publication does not simply render his observations as they were jotted down at the time, in secret, but has been embellished with knowledge only available in the postwar period; and yet the book manages to convey an immediacy, a sense of history unfolding in the present, of ominous terminology being created (or modified) on the fly—and thus at once summons up dread and anxiety in the reader, and elicits a scholarly absorption in the material to match the author’s own.

Klemperer’s linguistic archeology begins with Strafexpedition (“punitive expedition”), which denoted the violent hazing intended to intimidate Communists and chillingly recalls the genocidal approach of German Imperial troops in the Kaiser’s African colonies; it continues with such “ordinary” words, all lent new significance by their Nazi context, as Gefolgschaft (“retinue”), Weltanschauung (“worldview”), Staatsakt (“official occasion”), and System, which last the Nazis narrowed in sense to refer exclusively to the constitutional politics of the Weimar Republic they disdained, and eventually overthrew. Klemperer’s damning theoretical explanation for the Nazis’ aversion to the word System, beyond its simple identification with Weimar, draws brilliantly on the German idealist tradition:

The Kantian system is a logically constructed cognitive network designed to capture the totality of the world; for Kant—for the trained professional philosopher, as it were—to practice philosophy means to think systematically. But that is precisely what the National Socialist rejects with every fiber of his being, what his instinct for self-preservation compels him to abhor.

Klemperer notes the Nazis’ numbing fondness for the “historic”, the “heroic”, and especially the “fanatical”—a label to be applied with approval or disapproval depending on its subject—and dwells on their obsessive use of the superlative form to describe their own exploits, which he identifies as a habit borrowed from the carnival-barker character of the American press in the interwar period. In all such explications, his focus is also on the infectious spread of Nazi language throughout the German body politic, as evidenced by its adoption in the quotidian speech not only of hardline adherents to the National Socialist cause, but also of everyday, “apolitical” Germans, including those friendly to their Jewish compatriots, and even on occasion to Jewish Germans themselves.

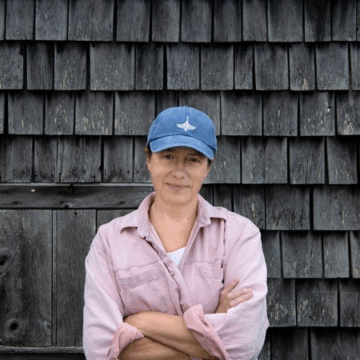

I’ve been thinking about Victor Klemperer recently, whenever I read Heather Cox Richardson’s “Letters from an American,” among the most heartening products of our current era’s media. A professor of American history at Boston College and the author of acclaimed studies of the Civil War, the Republican Party, and Wounded Knee, among other topics, Richardson began in 2019 publishing a regular newsletter on current events in American politics, and their echoes of earlier American history, as the first Trump administration entered its final, catastrophic year. Her daily briefings, now available on Substack, where they are followed by over a million readers, have taken on a greater urgency since Trump’s re-election in 2024: more dispassionate than Rebecca Solnit’s regular posts, with their hortatory, highly personal narrative style, Richardson’s meticulously footnoted “Letters” are an equally clear call to an American public in peril.

Richardson herself does not, of course, face the same threat to her existence as Klemperer, although she did appear on Charlie Kirk’s Professor Watchlist of academics who “discriminate against conservative students”—about which she has said that “I made the list not because of complaints about my teaching, but because of my public writing about politics.” Nor is her interest principally, or ever overtly, in language change under Trump—although implicit observations of linguistic corruption are inevitable, in coverage of a regime committed to disinformation and accusations of “fake news,” and whose leader’s background in real estate and reality TV gives his communications the very same placative flourish and preference for superlatives identified by Klemperer as the National Socialists’ early-20th-century “Americanist” style. And since Richardson’s “Letters” are also available in audio form on Substack, read by the author herself, she can be heard lending ironic force to such Trumpian terms of art as “enemy combatants” (Venezuelan fishermen summarily executed by American drones), “criminal aliens” (undocumented immigrants), and “less-lethal” weapons and tactics. (The last expression recalls the era of Bush Jr and Obama, in which “enhanced interrogation” of those subject to “extraordinary rendition” at Guantanamo was the cover name for torture, echoing the Nazis’ euphemistic verschärfte Vernehmung.) On occasion, Richardson resorts to spelling out the distancing punctuation, as when she talks about Trump’s “so-called border czar Tom Homan” or when, earlier this year, during the heyday of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, she would regularly pronounce its acronym “doggy”—when speaking in her own voice, rather than citing an administration source—instead of the Department’s preferred sound-styling of “Doge”: thus giving what had been intended to conjure up the noble atmosphere of Venetian oligarchy an absurdly lubricious tang.

What Richardson has most obviously in common with Klemperer is a clear-eyed, progressive humanism in the face of an increasingly inhumane regime. Klemperer went on after the war to join the SED, the Socialist Unity Party in the DDR, while Richardson, who identifies as a “Lincoln Republican,” is not a member of either major US party; and yet the two professors are nevertheless allied in their will to document for posterity the flagrant injustice and contempt for humankind exhibited by their respective national governments, three generations apart. And although the Romance language expert, with his 19th-century classical Bildung, relates anecdotes from his Ancient Greek lessons at Gymnasium and produces subordinate clauses worthy of Thoman Mann for his acid comments on Nazi barbarism, while the New Englander occasionally adopts a self-consciously plain-spoken tone to foreground Trump’s cruelty—“What are we doing here, folks” is her laconic protest at the Republican administration’s refusal to fund the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Plan—the two are equally, stirringly outraged by the dismantling of democracy in progress around them, in 1940s Germany as in 2020s America. Indeed, in their very different ways, whether by writing ornately correct German or jargon-free American English, Klemperer and Richardson both enact the possibility of remaining resistant to the toxic language, and thus to the odious ideology, of the various species of fascism infecting their republics. For, as Klemperer notes at several junctures, “language composes and thinks for us.”

Only once so far have I briefly feared for Richardson’s linguistic immunity, in a minor, but still telling locus. On October 21, 2025, in her comments on the Trump administration’s proposed bailout of Javier Milei’s government in Argentina, Richardson reported the following:

Bessent claims that Argentina is a “systematically important ally” of the U.S., but as economist Paul Krugman noted in his newsletter last week, that importance is not economic. Unlike Mexico, which borders the U.S. and which accounted for 10% of U.S. exports when the U.S. stepped in to help stabilize its economy in 1994, Argentina is not geographically close and accounts for less than 0.5% of U.S. exports.

Bessent, quoted verbatim here, has simply misspoken. He meant to say “systemically important” but, perhaps inhibited by a need to avoid echoing the “systemic racism” identified by the Critical Race Theory his regressive party has placed under erasure, he has mistakenly replaced the adverb indicating immanence with one denoting regularity.

So far so good: the present Treasury Secretary is no brighter a light than any other member of Trump’s Caligari-esque cabinet. What worried me was the following paragraph, in which Richardson adopts Bessent’s solecism in her own voice:

Argentina’s systematic importance to the administration is, as Krugman notes, both that the administration wants a Trump-like politician to succeed and apparently that some of Bessent’s hedge-fund billionaire associates invested heavily in Argentine bonds in a bet on Milei.

Surely not the most acute linguistic infection, since “systematic” does not obviously belong to the terminological armory of Trumpian pseudo-politics: but an indication nevertheless that even the most steadfast defenders of democracy and civility, like Richardson, are not entirely immune to the cognitive deformation afflicting American public life by way of its “leaders’” language.

Or perhaps Bessent’s use of a derivation of the word “system,” in however misunderstood a form, along with Richardson’s unquestioning adoption of that use, is precisely a sign that the US is not yet as far gone on the path to fascism as Germany was in the 1930s, when Klemperer noted the regime’s identification of the term System entirely pejoratively with the “systematic” parliamentary structure of Weimar, while the National Socialists were said to be a romantically “organic” Organisation. After all, on October 28, 2025, the eve of the anniversary of the Great Crash of 1929, Richardson recalled FDR’s election in 1932 and his proposal of the New Deal, what she terms a “new system”:

[W]hen World War II broke out, the new system enabled the United States to defend democracy successfully against fascists both at home—where by 1939 they had grown strong enough to turn out almost 20,000 people to a rally at Madison Square Garden—and abroad.

Trump’s Republicans are currently engaging in a frontal assault on that “new system,” on the “Big Government” that grew out of it, and which it required for its implementation. But at least MAGA has not yet demeaned the word “system” the way the Nazis demeaned it, for all that both “organic” movements struggle to think systematically. Let’s hope that Heather Cox Richardson, like Victor Klemperer, keeps an eye out for that particularly baleful development.

Note: LTI is available in English; the passages cited above are my own translations from the German.