by Mark Harvey

I have a horse named Mexico that tore one of his legs to shreds last week when he got caught in a wire fence. It was a bit of a fluke because we try to keep our fences tight and well-maintained. But one morning, a herd of 50 elk ran straight through the fence, leaving a twisted mess of wire. Mexico was grazing in that pasture and innocently stepped into the wire and then fought like hell to get out. He’s a horse with the sound temper of a saint, but any horse that gets a leg trapped will fight with all the force taught them through a million years of evolution. He was a mile from any trailer, and we had to limp him slowly off the meadow.

When we got him down to the barn, we loaded him up with three grams of phenylbutazone, better known as bute in the horse world, to ease the pain and give us a fighting chance of getting him in the trailer. Even with the bute running through his veins, he had a hard time bearing weight on the injured leg, and it took a long while to load him.

This is an animal with one instinct: to please. He is an ears-always-forward horse, seems to enjoy human company as much as the company of his hoofed friends, and rarely spooks at anything. He stands patiently when being shod, occasionally bending his neck as if to check on the quality of the farrier’s work.

He was sweating profusely through the pain and trauma, and it hurt all of us to watch him try to get into the trailer, even with the help of a ramp. Somehow, when animals get injured, we take it more personally than when human beings get hurt. At least I do. I joked to my ranch foreman that if it was him who had gotten cut up in the wire, I’m not sure I’d bother taking him to the vet—even if I could get him in the trailer.

We’re lucky to have arguably the best equine vet clinic in Western Colorado, aptly named Roaring Fork Equine Medical Center. It’s staffed with vets who know their science, anatomy, equine behavior, medicine, and surgical techniques as well as anyone. They have state-of-the-art mobile imaging machines and have seen so many gory injuries that an exposed bone, a ripped stomach, flayed ribs, or cancerous eyes never faze them.

So they received Mexico in stride, calmly explained his injury to me in lay terms—without simplifying the potential complications—and then went to work cleaning and debriding the wound, applying local antibiotics, and reducing the swelling with hypertonic salt packs. They called me twice a day to provide detailed reports on his progress and estimates of his healing time, and when the swelling was reduced, they sutured the wound. I’ve never had a fully licensed medical doctor give anywhere near the thorough explanations of my own maladies.

As I write this, I can already hear the shrill chorus of a thousand horsey people offering advice and scolding from their recliners in Kentucky, Texas, or California: “Should have known about the elk trashing the fence, never keep horses in a pasture with wire, that was too much bute, should have made the trailer entry easier.”

There are people who love horses and are superb riders that I would not call horsey people. They might have a mastery over the animals, but they’re not horsey. To me, horsey people are the ones who are pretty damn sure they know it all and are happy to share just how much they know with you, even if you just won the Rolex Grand Prix or a 100-mile endurance race on an Arab running through the desert.

If I had the choice between winning the Nobel Peace Prize for ending famine in Sub-Saharan Africa or getting horsey people to shut the f— up with their opinions on everything from bits to spurs, and fetlocks to foreplay, I might have to let the poor people in Africa suffer another year while I sorted things out among the jodhpur class. Not all horsey people are insufferable, and not all insufferable people are horsey, but the Venn diagram describing the two groups looks suspiciously like a circle.

I named that horse Mexico because there was already a horse on the ranch called Colorado and a dog called Texas. I’m not that imaginative, so Mexico was the obvious choice to round out the geography. Azerbaijan was out of the question because I can’t place it on the map, and Arkansas has a governor who has spoiled that name.

If you think about the millions of years in a horse’s evolution, it’s kind of amazing that we can saddle them, ride them, work cattle on them, run them over huge jumps, and get them into trailers.

What most people don’t know is that horses evolved in North America over some fifty million years, and only went extinct on this continent about 13,000 years ago. They are part of the Perissodactyla order, a group of ungulates characterized by an odd number of toes on each foot. Other animals in that order include tapirs and rhinoceroses.

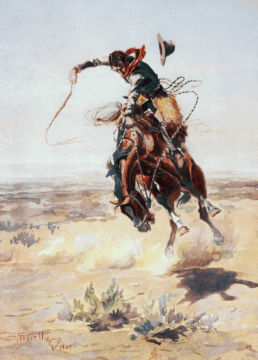

Over their millions of years roaming North America, they spent a lot of time shaking big cats such as the saber-toothed tigers and later, mountain lions, off their backs. And also defending themselves against wolves using violent kicks. So the ones that survived were very good at kicking, biting, bucking, and fleeing.

Thousands of years of breeding and domestication may have mellowed horses somewhat, but they are still hardwired to get strange things off their back, listen for weird sounds, and kick objects that might appear to be predators. Hence, the process of training a colt involves a lot of desensitizing with touch, introducing them to threatening things like loose tarps and loud noises, groundwork with halters and driving reins, and finally, a blanket and saddle.

Horse training in the West has evolved a lot from the “buster days” when cowboys would rope a two-year-old, snub it to a post, get a saddle on, and then get their best bronc riders up in the saddle, inevitably leading to a wild, bucking ride. Nowadays, most men and women take a lot more time doing ground work before ever getting into the saddle. It’s easy to criticize the old ways, but there was a practical necessity to “break” a horse in a short amount of time. People in those times simply didn’t have days and days to train horses, and they needed the animals to get to work quickly.

A good bronc rider is something to watch. It’s a fantastic mix of balance and anticipating the animal’s next move. I worked a stint on the Bell Ranch in New Mexico, a sprawling place of more than 200,000 acres, and it had some of the best cowboys I’ve ever seen. The ranch had a herd of more than a hundred horses, and every spring the men would go out and rope a few two-year-olds, do a little groundwork, and then jump in the saddle. How they stayed on some of those animals was beyond me. And when they were thrown, they got right back into the saddle for more.

They were tough guys, and the first time we played a game of football on a field of rocks and cactus, I assumed it was touch football. Not for them. Full tackle with no pads and no helmets.

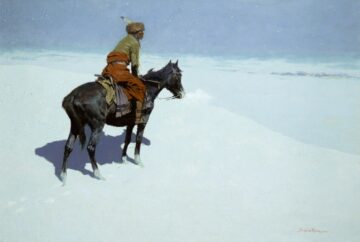

During the spring roundup at The Bell Ranch, we were each assigned a string of five or six horses to use while gathering, branding, and vaccinating cattle over a period of about two weeks on a sprawling camping trip around the ranch. There was so much riding that each man needed the extra mounts to rotate through, sometimes using two in the same day. Every morning while it was still dark, two wranglers would gather the remuda of seventy or so horses wherever we were camping and bring them into a small makeshift corral of ropes strung tightly between stakes. Then the wagon boss and one other man would enter the pen, and rope whichever horse you called out to use that day.

The cowboys would yell out names like Pardner, Blue, Boozer, Shorty, Frosty, and Smoke, and the two guys in the pen would throw graceful loops into the herd to land quietly around the neck of the chosen mount. How they could remember so many different horses when some of them looked nearly identical was beyond me.

If you’re ever wondering why so many men who’ve never worked on a ranch wear the full kit of boots, snap shirts, and a ten-gallon Stetson, it has to do with wanting to be more like those men. Plus it’s a good look if done right.

We’ve confined Mexico to a small pen and are bandaging and rebandaging his wound every two days. He stands patiently for the treatment and appears to be healing nicely. Only time will tell how his leg is in the future, but I’m hopeful.

I haven’t received the vet bill yet, but I know that with the imaging, the days spent at the clinic, the local antibiotics, and other medicine, it will be in the thousands. The original purchase price of a ranch horse is usually a fraction of the costs that run over the animal’s lifetime. Between farriers, vets, and winter hay, the bills never end.

I love to ride, but I take as much or more pleasure in seeing other people enjoy my horses, even if they only visit the ranch a few times per year. A few hours crossing beautiful country on the animals often brings peace and healing to those wrestling with life’s sorrows and setbacks. Mexico, in particular, with his sweet disposition is a favorite among friends and nearly everyone who has ridden him is convinced that they have a special bond. I won’t spoil that impression by telling them that he acts like an overgrown puppy around everyone.