Ed Simon in The Hedgehog Review:

Despite the stereotype of being the Norman Rockwell of verse, Robert Frost’s standing, even sixty-one years after his death, remains blue-chip, still perhaps the most famous American poet among the general public. Frost’s work remains anthologized and interpreted, and taught in secondary and undergraduate classrooms; his lyrics among the handful that can be expected to be namedropped as a reader’s favorite poem (two roads and all of that). If anything, Frost has suffered from the albatross of presumed accessibility. Among the luminaries of American Modernism, Ezra Pound was experimental, T.S. Eliot cerebral, H.D. hermetic, Langston Hughes revolutionary, Wallace Stevens incandescent, and William Carlos Williams visionary, but Frost is readable. David Orr writes in his excellent book-length close reading The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong (2015) that Frost is a poet whose “signature phrases have become so ubiquitous, so much a part of everything from coffee mugs to refrigerator magnets to graduation speeches” that it can become easy to forget the man who penned such phrases.

Despite the stereotype of being the Norman Rockwell of verse, Robert Frost’s standing, even sixty-one years after his death, remains blue-chip, still perhaps the most famous American poet among the general public. Frost’s work remains anthologized and interpreted, and taught in secondary and undergraduate classrooms; his lyrics among the handful that can be expected to be namedropped as a reader’s favorite poem (two roads and all of that). If anything, Frost has suffered from the albatross of presumed accessibility. Among the luminaries of American Modernism, Ezra Pound was experimental, T.S. Eliot cerebral, H.D. hermetic, Langston Hughes revolutionary, Wallace Stevens incandescent, and William Carlos Williams visionary, but Frost is readable. David Orr writes in his excellent book-length close reading The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong (2015) that Frost is a poet whose “signature phrases have become so ubiquitous, so much a part of everything from coffee mugs to refrigerator magnets to graduation speeches” that it can become easy to forget the man who penned such phrases.

More here.

Technology is changing the world, in good and bad ways. Artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, biological engineering, and climate change are dramatically altering the parameters of human life. What can we say about how this will extend into the future? Will the pace of change level off, or smoothly continue, or hit a singularity in a finite time? In this informal solo episode, I think through what I believe will be some of the major forces shaping how human life will change over the decades to come, exploring the very real possibility that we will experience a dramatic phase transition into a new kind of equilibrium.

Technology is changing the world, in good and bad ways. Artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, biological engineering, and climate change are dramatically altering the parameters of human life. What can we say about how this will extend into the future? Will the pace of change level off, or smoothly continue, or hit a singularity in a finite time? In this informal solo episode, I think through what I believe will be some of the major forces shaping how human life will change over the decades to come, exploring the very real possibility that we will experience a dramatic phase transition into a new kind of equilibrium. On my last visit to the National Gallery in London in October 2022, during Frieze Week, the wall beneath Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers still displayed noticeable palm-sized daubs of unmatched gray paint. The day before, Just Stop Oil protestors Phoebe Plummer, and Anna Holland

On my last visit to the National Gallery in London in October 2022, during Frieze Week, the wall beneath Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers still displayed noticeable palm-sized daubs of unmatched gray paint. The day before, Just Stop Oil protestors Phoebe Plummer, and Anna Holland  When it comes to our understanding of the world, we are all like the blind men in the story of the blind men and the elephant. We each know the elephant from our own small vantage point, and what we know is partial and prone to distortions. It is from speaking to one another, reading one another, that a more accurate picture appears. Unfortunately, too often, those we speak to and read come from places very close to ours, whether physically or ideologically, and so the elephant we see together looks to us uncannily like something else, like a wall or a weapon or a trophy, perhaps. I would like to describe the elephant, the world, as I perceive it from my vantage point in Lahore, Pakistan, in the early months of the year 2024. I do this in the hope that each of us, in describing it, helps all of us see it a little better.

When it comes to our understanding of the world, we are all like the blind men in the story of the blind men and the elephant. We each know the elephant from our own small vantage point, and what we know is partial and prone to distortions. It is from speaking to one another, reading one another, that a more accurate picture appears. Unfortunately, too often, those we speak to and read come from places very close to ours, whether physically or ideologically, and so the elephant we see together looks to us uncannily like something else, like a wall or a weapon or a trophy, perhaps. I would like to describe the elephant, the world, as I perceive it from my vantage point in Lahore, Pakistan, in the early months of the year 2024. I do this in the hope that each of us, in describing it, helps all of us see it a little better. Scientists at a recently opened cancer institute at

Scientists at a recently opened cancer institute at  Great tracts of culture, notably the

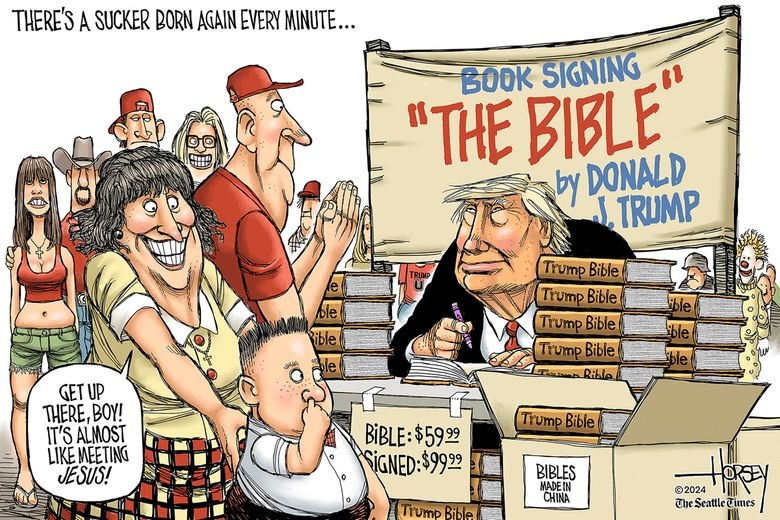

Great tracts of culture, notably the  P.T. Barnum, the great 19th century showman, circus owner and hoax promoter, is quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Donald J. Trump, the great 21st century con man, political phenomenon and hoax promoter, would heartily agree. Trump has built a weirdly successful career in business, entertainment and politics based on his uncanny ability to convince legions of suckers to buy into his self-aggrandizing schemes, from Trump University, the Trump charity and the Big Lie, to his latest scam tricking thousands of poor chumps into chipping in to pay his millions of dollars in legal bills.

P.T. Barnum, the great 19th century showman, circus owner and hoax promoter, is quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Donald J. Trump, the great 21st century con man, political phenomenon and hoax promoter, would heartily agree. Trump has built a weirdly successful career in business, entertainment and politics based on his uncanny ability to convince legions of suckers to buy into his self-aggrandizing schemes, from Trump University, the Trump charity and the Big Lie, to his latest scam tricking thousands of poor chumps into chipping in to pay his millions of dollars in legal bills. One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as

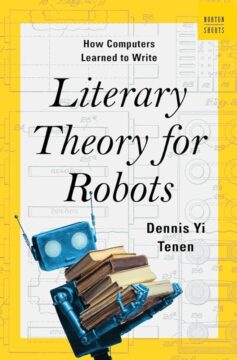

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as  Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as

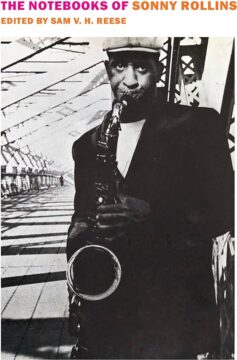

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as  It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.”

It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.” One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own.

One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own.