by Tim Sommers

(The butter robot realizing the sole purpose of its existence is to pass the butter.)

In the halcyon days of “self-driving cars are six months away,” you probably encountered this argument. “If self-driving cars work, they will be safer than cars driven by humans.” Sure. If, by “they work,” you mean that, among other things, they are safer than cars driven by humans, then, it follows, that they will be safer than cars driven by humans, if they work. That’s called begging the question. Unfortunately, the tech world has more than it’s share of such sophistries. AI, especially.

Exhibit #1

In a recent issue of The New Yorker, in an article linked to on 3 Quarks Daily, Geoffrey Hinton, the “Godfather of AI,” tells Joshua Rothman:

“‘People say, [of Large Language Models like ChatGPT that] It’s just glorified autocomplete…Now, let’s analyze that…Suppose you want to be really good at predicting the next word. If you want to be really good, you have to understand what’s being said. That’s the only way. So, by training something to be really good at predicting the next word, you’re actually forcing it to understand. Yes, it’s ‘autocomplete’—but you didn’t think through what it means to have a really good autocomplete.’ Hinton thinks that ‘large language models,’ such as GPT, which powers OpenAI’s chatbots, can comprehend the meanings of words and ideas.”

This is a morass of terrible reasoning. But before we even get into it, I have to say that thinking that an algorithm that works by calculating the odds of what the next word in a sentence will be “can comprehend the meanings of words and ideas” is a reductio ad absurdum of the rest. (In fairness, Rothman attributes that view to Hinton, but doesn’t quote him as saying that, so maybe that’s not really Rothman’s position. But it seems to be.)

Hinton says “training something to be really good at predicting the next word, you’re actually forcing it to understand.” There’s no support for the claim that the only way to be good at predicting the next word in a sentence is to understand what is being said. LMMs prove that, they don’t undermine it. Further, if anything, prior experience suggests the opposite. Calculators are not better at math than most people because they “understand” numbers. Read more »

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends.

For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends. B

B Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of

Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of  In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.”

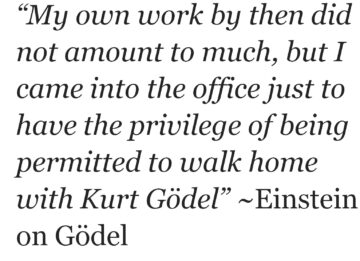

In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.” When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems.

When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems. In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community.

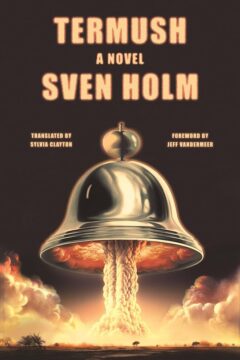

In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community. Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe.

Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe. Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life.

Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life. Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses?

Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses? Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me.

Two weeks after my wife died this past October, she briefly returned. Or so it seemed to me. I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

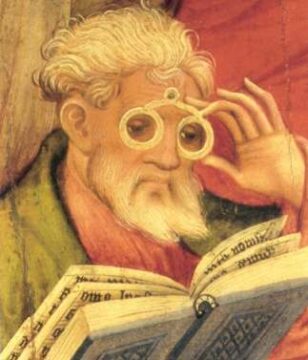

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).