We’ve Come to Expect

—an excerpt

Let’s remember not only the local wars

over claims but a late conflict of siblings

in aristocracy and the stock market,

………….. sharing destruction.

Or recollect the brothers who stayed back east

laboring in the shoe factory, or their

bosses who summered hunting in Scotland and

………….. reside forever

in the protestant cemetery at Rome

among cats, the pyramid of Cestius,

and Keats’s grave. What use are those forefathers

…………..to our condition?

We want comfort: . . .

…………..…………..~~~~

…………..Or say: We’re sixty

…………..years old we know better

…………..and do less. Things we

…………..know better are antinomian

…………..adventure, sequent despair,

…………..error, self-deception, failure,

…………..and good cheer. No wonder

…………..that we’d prefer, with

…………..the dying Irish poet, to

…………..be “young” and “ignorant.”

by Donald Hall

from The Museum of Clear Ideas

Ticknor and Fields 1993

Biologists have discovered another incredible skill of ants that put humans to shame—they have a special technique to avoid traffic jams. Scientists from Texas Tech University and other institutions studied the 20-minute rhythms of the Leptothorax ant and discovered that their clever synchronization skills allowed them to avoid congestion. Their findings are published in a Proceedings of the Royal Society study.

Biologists have discovered another incredible skill of ants that put humans to shame—they have a special technique to avoid traffic jams. Scientists from Texas Tech University and other institutions studied the 20-minute rhythms of the Leptothorax ant and discovered that their clever synchronization skills allowed them to avoid congestion. Their findings are published in a Proceedings of the Royal Society study. On that gray February morning, the exhibit galleries smelled of perfumed wool and vibrated with a hushed reverence for Picasso’s creatures—two-legged, four-legged, winged, taloned, hooved. A man with a goat, a tiny horse with casters for feet, a girl jumping rope, Picasso’s ever-present Minotaur. And many, many women.

On that gray February morning, the exhibit galleries smelled of perfumed wool and vibrated with a hushed reverence for Picasso’s creatures—two-legged, four-legged, winged, taloned, hooved. A man with a goat, a tiny horse with casters for feet, a girl jumping rope, Picasso’s ever-present Minotaur. And many, many women. The Artificial Intelligence landscape is changing with remarkable speed these days, and the capability of Large Language Models in particular has led to speculation (and hope, and fear) that we could be on the verge of achieving

The Artificial Intelligence landscape is changing with remarkable speed these days, and the capability of Large Language Models in particular has led to speculation (and hope, and fear) that we could be on the verge of achieving  Henry Farrell: You’ve written a very influential

Henry Farrell: You’ve written a very influential  On the outskirts of Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany, nestled among car dealerships and hardware shops, sits a two-storey factory stuffed with solar-power secrets. It’s here where UK firm

On the outskirts of Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany, nestled among car dealerships and hardware shops, sits a two-storey factory stuffed with solar-power secrets. It’s here where UK firm  As we age, our memory declines. This is an ingrained assumption for many of us; however, according to neuroscientist Dr. Richard Restak, a neurologist and clinical professor at George Washington Hospital University School of Medicine and Health, decline is not inevitable. The author of more than 20 books on the mind, Dr. Restak has decades’ worth of experience in guiding patients with memory problems. “The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind,” Dr. Restak’s latest book, includes tools such as mental exercises, sleep habits and diet that can help boost memory.

As we age, our memory declines. This is an ingrained assumption for many of us; however, according to neuroscientist Dr. Richard Restak, a neurologist and clinical professor at George Washington Hospital University School of Medicine and Health, decline is not inevitable. The author of more than 20 books on the mind, Dr. Restak has decades’ worth of experience in guiding patients with memory problems. “The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind,” Dr. Restak’s latest book, includes tools such as mental exercises, sleep habits and diet that can help boost memory. Even though Kierkegaard treats despair as a spiritual and existential condition rather than just a psychological state, The Sickness Unto Death sparkles with psychological insight. Especially compelling is his diagnosis of the different forms of despair that arise from an imbalance between the various pairs that make up the human synthesis (those first folds in our sheets of paper). Too much necessity, and we lose all imagination and hope—we cannot breathe; too much possibility, and we float airily, ineffectually, above our own lives. Too much finitude, and we lose ourselves in trivial things; too much infinitude, and we’re disconnected from the world. Since life is so rarely in balance, despair is the inevitable state—but understanding this, for Kierkegaard, opens up a renewed perspective on how to live with this inevitability.

Even though Kierkegaard treats despair as a spiritual and existential condition rather than just a psychological state, The Sickness Unto Death sparkles with psychological insight. Especially compelling is his diagnosis of the different forms of despair that arise from an imbalance between the various pairs that make up the human synthesis (those first folds in our sheets of paper). Too much necessity, and we lose all imagination and hope—we cannot breathe; too much possibility, and we float airily, ineffectually, above our own lives. Too much finitude, and we lose ourselves in trivial things; too much infinitude, and we’re disconnected from the world. Since life is so rarely in balance, despair is the inevitable state—but understanding this, for Kierkegaard, opens up a renewed perspective on how to live with this inevitability. Elizabeth Bishop delighted in the postcard. It suited her poetic subject matter and her way of life—this poet of travel who was more often on the move than at home, “wherever that may be,” as she put it in her poem “Questions of Travel.” She told James Merrill in a postcard written in 1979 that she seldom wrote “anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.”

Elizabeth Bishop delighted in the postcard. It suited her poetic subject matter and her way of life—this poet of travel who was more often on the move than at home, “wherever that may be,” as she put it in her poem “Questions of Travel.” She told James Merrill in a postcard written in 1979 that she seldom wrote “anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.” K

K W

W Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion.

Rather than focusing on how people and societies think and talk about morality, normative ethicists try to figure out which things are, simply, morally good or bad, and why. The philosophical sub-field of meta-ethics adopts, naturally, a ‘meta-’ perspective on the kinds of enquiry that normative ethicists engage in. It asks whether there are objectively correct answers to these questions about good or bad, or whether ethics is, rather, a realm of illusion or mere opinion. This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “

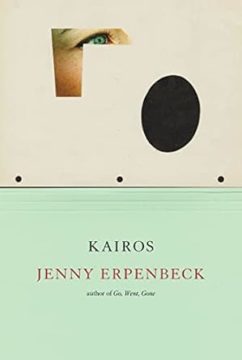

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the International Year of Quinoa (IYQ), a celebratory initiative created by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. At the inaugural 2013 IYQ, Evo Morales, then president of Bolivia, proclaimed that quinoa was “ Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.”

Born in East Berlin in 1967, Jenny Erpenbeck was 22 when the Wall that had divided her native city for her entire life fell. The socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), the only country she had known, vanished overnight. By her own account, in the essays collected in Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces (2018), this historical rupture confronted her with fundamental questions about continuity and change, agency and contingency, borders and identity, liberation and loss. Although these questions have animated her fiction for more than twenty years, her most recent novel, Kairos (2021), is the first to be centered on how the radically transformative period of German reunification was experienced by those who found themselves, as she writes, “at home on the wrong side.” On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.”

On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged from a New York City courtroom, where he had testified in a civil trial alleging that he and others in the Trump Organization had committed fraud, and gave himself a great review. “I think it went very well,” he told reporters. “If you were there, and you listened, you’d see what a scam this is.” He meant that the case was a scam and not that his company was. “Everybody saw what happened today,” he went on. “And it was very conclusive.”