R W B Lewis in The New York Review:

Shadow and Act contains Ralph Ellison’s real autobiography—in the form of essays and interviews—as distinguished from the symbolic version given in his splendid novel of 1952, Invisible Man Some of the twenty-odd items in it were written as early as 1942, and not all of them have been published before. One or two were rejected by liberal periodicals, apparently because Ellison insisted on saying that Negro American life was not everywhere as hellish or as inert or as devastated by hatred and self-hatred as it was sometimes alleged; it is not unlikely that liberal criticism will be equally impatient with this new book. Most of the pieces, were, however, written after Invisible Man and in part are a consequence of it. They may even help to explain the long gap of time between Ellison’s first novel and its much awaited successor. There have been other theories about this delay: for example, an obituary notice by Le Roi Jones who, in a recent summary of the supposedly lethal effect of America upon its Negro writers, referred to Ellison as “silenced and fidgeting away in some college.” But he has not been silent, much less silenced—by White America or anything else. The experiences of writing Invisible Man and of vaulting on his first try “over the parochial limits of most Negro fiction” (as Richard G. Stern says in an interview), and, as a result, of being written about as a literary and sociological phenomenon, combined with sheer compositional difficulties, seem to have driven Ellison to search out the truths of his own past. Inquiring into his experience, his literary and musical education, Ellison has come up with a number of clues to the fantastic fate of trying to be at the same time a writer, a Negro, an American, and a human being.

Shadow and Act contains Ralph Ellison’s real autobiography—in the form of essays and interviews—as distinguished from the symbolic version given in his splendid novel of 1952, Invisible Man Some of the twenty-odd items in it were written as early as 1942, and not all of them have been published before. One or two were rejected by liberal periodicals, apparently because Ellison insisted on saying that Negro American life was not everywhere as hellish or as inert or as devastated by hatred and self-hatred as it was sometimes alleged; it is not unlikely that liberal criticism will be equally impatient with this new book. Most of the pieces, were, however, written after Invisible Man and in part are a consequence of it. They may even help to explain the long gap of time between Ellison’s first novel and its much awaited successor. There have been other theories about this delay: for example, an obituary notice by Le Roi Jones who, in a recent summary of the supposedly lethal effect of America upon its Negro writers, referred to Ellison as “silenced and fidgeting away in some college.” But he has not been silent, much less silenced—by White America or anything else. The experiences of writing Invisible Man and of vaulting on his first try “over the parochial limits of most Negro fiction” (as Richard G. Stern says in an interview), and, as a result, of being written about as a literary and sociological phenomenon, combined with sheer compositional difficulties, seem to have driven Ellison to search out the truths of his own past. Inquiring into his experience, his literary and musical education, Ellison has come up with a number of clues to the fantastic fate of trying to be at the same time a writer, a Negro, an American, and a human being.

It is hard at the best of times to be even two of those things; the attempt to be all four must be called gallant.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

Note: Photograph of the sculpture Invisible Man on Riverside Drive in New York by Azra.

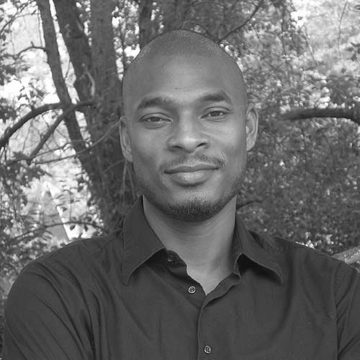

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length. If the great campaigners for free speech of the past, such as Baruch Spinoza or Mary Wollstonecraft or Frederick Douglass, were alive today, “they would surely declare the 21st century an unprecedented golden age”. So suggests Jacob Mchangama in his

If the great campaigners for free speech of the past, such as Baruch Spinoza or Mary Wollstonecraft or Frederick Douglass, were alive today, “they would surely declare the 21st century an unprecedented golden age”. So suggests Jacob Mchangama in his  In a time

In a time Do laws criminalizing prostitution violate the Constitution? Probably. Until recently, such a proposition would have been as absurd as

Do laws criminalizing prostitution violate the Constitution? Probably. Until recently, such a proposition would have been as absurd as

“If a fat person behaves badly in an artistic context, then they are doubly misbehaving. Being fat is a transgression in itself. . . . An obese person’s simple existence constitutes misbehaving,” Susiraja once remarked in an interview. The impropriety she mentions runs rampant throughout her self-portraiture. Part of this is fueled by her talent for turning commonplace items—food, toys, women’s shoes, boring underwear—into uncanny and even oddly visceral props. Take Happy Meal, 2011, in which various lengths of apple peel delicately grace the top of the artist’s plump bare foot, calling to mind old scabs, skin ulcers; or Let’s Call, 2016, a picture of Susiraja hunched over, an orange rotary telephone shoved between her legs and trapped in the crotch of a hideous pair of pantyhose that have been pulled down around her knees. The phone makes me think of a miscarried infant—the long, coiled cord of the handset, which is draped over the artist’s neck, feels more than a little umbilical.

“If a fat person behaves badly in an artistic context, then they are doubly misbehaving. Being fat is a transgression in itself. . . . An obese person’s simple existence constitutes misbehaving,” Susiraja once remarked in an interview. The impropriety she mentions runs rampant throughout her self-portraiture. Part of this is fueled by her talent for turning commonplace items—food, toys, women’s shoes, boring underwear—into uncanny and even oddly visceral props. Take Happy Meal, 2011, in which various lengths of apple peel delicately grace the top of the artist’s plump bare foot, calling to mind old scabs, skin ulcers; or Let’s Call, 2016, a picture of Susiraja hunched over, an orange rotary telephone shoved between her legs and trapped in the crotch of a hideous pair of pantyhose that have been pulled down around her knees. The phone makes me think of a miscarried infant—the long, coiled cord of the handset, which is draped over the artist’s neck, feels more than a little umbilical. One day, as a small boy, I was copying the portrait of Napoleon. His left eye was giving me trouble. Already I had erased the drawing of it several times. My father leaned over and lovingly corrected my work. I threw the paper and pencil across the room, saying “now it is your drawing, not mine.” Two cannot make a single drawing. I am sure the most skillful imitation can be detected by the originator. The sheer delight in the act of drawing has its way in the drawing and that also is a quality that the imitator can’t imitate. The personal abstraction, the rapport between subject and the thought also are unimitatable.

One day, as a small boy, I was copying the portrait of Napoleon. His left eye was giving me trouble. Already I had erased the drawing of it several times. My father leaned over and lovingly corrected my work. I threw the paper and pencil across the room, saying “now it is your drawing, not mine.” Two cannot make a single drawing. I am sure the most skillful imitation can be detected by the originator. The sheer delight in the act of drawing has its way in the drawing and that also is a quality that the imitator can’t imitate. The personal abstraction, the rapport between subject and the thought also are unimitatable. From the moment it appeared in April 1903, The Souls of Black Folk caused a sensation. Among black readers,

From the moment it appeared in April 1903, The Souls of Black Folk caused a sensation. Among black readers,  The recent

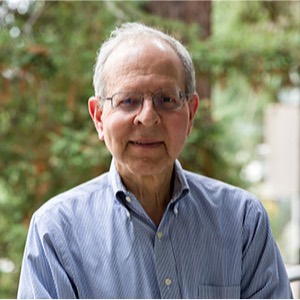

The recent  Modern particle physics is a victim of its own success. We have extremely good theories — so good that it’s hard to know exactly how to move beyond them, since they agree with all the experiments. Yet, there are strong indications from theoretical considerations and cosmological data that we need to do better. But the leading contenders, especially supersymmetry, haven’t yet shown up in our experiments, leading some to wonder whether anthropic selection is a better answer. Michael Dine gives us an expert’s survey of the current situation, with pointers to what might come next.

Modern particle physics is a victim of its own success. We have extremely good theories — so good that it’s hard to know exactly how to move beyond them, since they agree with all the experiments. Yet, there are strong indications from theoretical considerations and cosmological data that we need to do better. But the leading contenders, especially supersymmetry, haven’t yet shown up in our experiments, leading some to wonder whether anthropic selection is a better answer. Michael Dine gives us an expert’s survey of the current situation, with pointers to what might come next. “Can you see me?” In the age of video calls, this has become a common question. But when posed to philosopher David Chalmers, it takes on a deeper significance. Regarding the basic version of virtual reality (VR) in which we’re having our conversation, Chalmers suggests that “some very conservative philosophers would say no, I am merely seeing a pattern of pixels on a screen and I’m not seeing you behind it.” But Chalmers has a different view: “Yes, I’m seeing you perfectly,” he replies, covering both meanings with his answer. His seemingly simple claim has implications not just for the possibilities of virtual reality, but the nature of actual reality, too.

“Can you see me?” In the age of video calls, this has become a common question. But when posed to philosopher David Chalmers, it takes on a deeper significance. Regarding the basic version of virtual reality (VR) in which we’re having our conversation, Chalmers suggests that “some very conservative philosophers would say no, I am merely seeing a pattern of pixels on a screen and I’m not seeing you behind it.” But Chalmers has a different view: “Yes, I’m seeing you perfectly,” he replies, covering both meanings with his answer. His seemingly simple claim has implications not just for the possibilities of virtual reality, but the nature of actual reality, too. Lee wanted to make Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as a movie that was by China, for China, while the country was at this turning point. But though it was embraced around the world, it failed to meet that criterion of the holy grail production, since it was of little interest to audiences in China. There, moviegoers were watching True Lies because it was the kind of action-packed spectacular their own country’s filmmakers couldn’t produce. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had seemed so novel in America, was old hat to Chinese moviegoers reared on kung fu.

Lee wanted to make Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as a movie that was by China, for China, while the country was at this turning point. But though it was embraced around the world, it failed to meet that criterion of the holy grail production, since it was of little interest to audiences in China. There, moviegoers were watching True Lies because it was the kind of action-packed spectacular their own country’s filmmakers couldn’t produce. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had seemed so novel in America, was old hat to Chinese moviegoers reared on kung fu. S

S

One of the most famous and admired African-American women in U.S. history, Sojourner Truth sang, preached, and debated at camp meetings across the country, led by her devotion to the antislavery movement and her ardent pursuit of women’s rights. Born into slavery in 1797, Truth fled from bondage some 30 years later to become a powerful figure in the progressive movements reshaping American society.

One of the most famous and admired African-American women in U.S. history, Sojourner Truth sang, preached, and debated at camp meetings across the country, led by her devotion to the antislavery movement and her ardent pursuit of women’s rights. Born into slavery in 1797, Truth fled from bondage some 30 years later to become a powerful figure in the progressive movements reshaping American society.