Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

Ars Technica: You make frequent references not just to The Matrix but to other classic works in science fiction in your book. What is it about such works that resonate so strongly with philosophers?

Ars Technica: You make frequent references not just to The Matrix but to other classic works in science fiction in your book. What is it about such works that resonate so strongly with philosophers?

David Chalmers: The Wachowskis do a beautiful job in The Matrix of illustrating so many deep philosophical ideas. And Stanislaw Lem is clearly a very deep philosopher who reflected on some of these scenarios very early on in the 1950s and 1960s, well before any philosophers had. I think almost every science fiction writer is a kind of philosopher because what is a science fiction story but a kind of thought experiment? What if there were machines as intelligent as humans, or what if we were living in a simulation? They go on to reason about the consequences. In a way, that’s what philosophers do, too. We think about these scenarios, and we reason about what follows. When done well, that can bring out something important about the nature of the mind or the nature of reality.

More here.

When I was a journalist for The Times (London) in Moscow in December 1992, I saw a print-out of a speech by the then Russian foreign minister, Andrei Kozyrev, warning that if the West continued to attack vital Russian interests and ignore Russian protests, there would one day be a dangerous backlash. A British journalist had scrawled on it a note to an American colleague, “Here are more of Kozyrev’s ravings.”

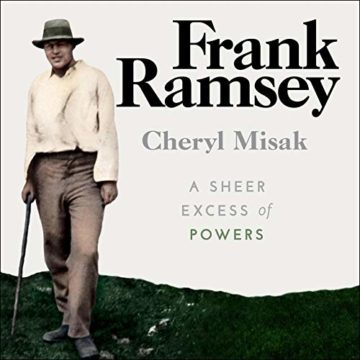

When I was a journalist for The Times (London) in Moscow in December 1992, I saw a print-out of a speech by the then Russian foreign minister, Andrei Kozyrev, warning that if the West continued to attack vital Russian interests and ignore Russian protests, there would one day be a dangerous backlash. A British journalist had scrawled on it a note to an American colleague, “Here are more of Kozyrev’s ravings.” Cheryl Misak’s new book is the first intellectual biography of Frank Plumpton Ramsey, a brilliant but tragically short-lived scholar who illuminated Cambridge in the 1920s. The biography has been eagerly awaited by many of us, in several fields, who’ve built chunks of our own careers from fragments of Ramsey’s astonishing meteorite.

Cheryl Misak’s new book is the first intellectual biography of Frank Plumpton Ramsey, a brilliant but tragically short-lived scholar who illuminated Cambridge in the 1920s. The biography has been eagerly awaited by many of us, in several fields, who’ve built chunks of our own careers from fragments of Ramsey’s astonishing meteorite. When you wake up in the morning, how do you know who you are? You might say something like: ‘Because I remember.’ A perfectly good answer, and one with a venerable history. The English philosopher John Locke, for example, considered memory to be the foundation of identity. ‘Consciousness always accompanies thinking,’ he wrote in 1694. ‘And as far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past Action or Thought, so far reaches the Identity of that Person.’

When you wake up in the morning, how do you know who you are? You might say something like: ‘Because I remember.’ A perfectly good answer, and one with a venerable history. The English philosopher John Locke, for example, considered memory to be the foundation of identity. ‘Consciousness always accompanies thinking,’ he wrote in 1694. ‘And as far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past Action or Thought, so far reaches the Identity of that Person.’ The Cold War ended 30 years ago. But since the 2007-08 financial crisis, it has not only returned but mutated into a hybrid lukewarm war. And with the United States and its European allies now struggling to manage the threat of a Russian attack on Ukraine, the specter of a hot war is looming. The 1938

The Cold War ended 30 years ago. But since the 2007-08 financial crisis, it has not only returned but mutated into a hybrid lukewarm war. And with the United States and its European allies now struggling to manage the threat of a Russian attack on Ukraine, the specter of a hot war is looming. The 1938  Olga Tokarczuk’s twelfth book, the novel The Books of Jacob, first published in Poland in 2014 to great acclaim and considerable controversy, kicks off in 1752 in Rohatyn, in what is now western Ukraine, and winds up in a cave near Korolówka, now eastern Poland, where a family of local Jews has hidden from the Holocaust. Between mid-18th-century Rohatyn and mid-20th-century Korolówka, Olga traverses the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in search of the manifold secrets of Jacob Frank, a highly charismatic real historical figure, beloved and despised by his contemporaries, the leader of a wildly heretical Jewish sect that converted in different moments to both Catholicism and Islam.

Olga Tokarczuk’s twelfth book, the novel The Books of Jacob, first published in Poland in 2014 to great acclaim and considerable controversy, kicks off in 1752 in Rohatyn, in what is now western Ukraine, and winds up in a cave near Korolówka, now eastern Poland, where a family of local Jews has hidden from the Holocaust. Between mid-18th-century Rohatyn and mid-20th-century Korolówka, Olga traverses the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in search of the manifold secrets of Jacob Frank, a highly charismatic real historical figure, beloved and despised by his contemporaries, the leader of a wildly heretical Jewish sect that converted in different moments to both Catholicism and Islam. For most of November, 2020, the director Céline Sciamma didn’t have any lamps in her apartment. They were all on the set of her fifth film, “Petite Maman.” Each day, she got ready before sunrise, leaving her Paris apartment in the dark. One morning when she was running late, she rushed into her room and hit something with her foot. It hurt, a lot, but she put on her shoes and hurried to the set, where she sat around for three hours, waiting for everyone else to be ready. Suddenly, she heard a familiar, uneven step behind her: that of her maternal grandmother, Marie-Paule Chiron, who walked with a limp and who had been dead for six years. Sciamma jumped from her chair, remembering too late her injured foot. Instinctively, she reached for the closest support: a silver-topped walking stick that had belonged to Marie-Paule.

For most of November, 2020, the director Céline Sciamma didn’t have any lamps in her apartment. They were all on the set of her fifth film, “Petite Maman.” Each day, she got ready before sunrise, leaving her Paris apartment in the dark. One morning when she was running late, she rushed into her room and hit something with her foot. It hurt, a lot, but she put on her shoes and hurried to the set, where she sat around for three hours, waiting for everyone else to be ready. Suddenly, she heard a familiar, uneven step behind her: that of her maternal grandmother, Marie-Paule Chiron, who walked with a limp and who had been dead for six years. Sciamma jumped from her chair, remembering too late her injured foot. Instinctively, she reached for the closest support: a silver-topped walking stick that had belonged to Marie-Paule. February is Black History Month in the US, a month dedicated to paying tribute to Black American history. It is also a month dedicated to raising awareness about the deeply inequitable treatment that Black communities have endured in the US, as well as the incredible contributions Black individuals and communities have made to the wellbeing of all people, despite the disadvantages that exist to this day. This article names twelve of the many Black Americans in history who have had, and continue to have, a profound impact on the health and wellness of people in the US and worldwide.

February is Black History Month in the US, a month dedicated to paying tribute to Black American history. It is also a month dedicated to raising awareness about the deeply inequitable treatment that Black communities have endured in the US, as well as the incredible contributions Black individuals and communities have made to the wellbeing of all people, despite the disadvantages that exist to this day. This article names twelve of the many Black Americans in history who have had, and continue to have, a profound impact on the health and wellness of people in the US and worldwide. The historian Marcus Rediker opens “

The historian Marcus Rediker opens “