Nick Zangwill in Aeon:

If you care about animals, you should eat them. It is not just that you may do so, but you should do so. In fact, you owe it to animals to eat them. It is your duty. Why? Because eating animals benefits them and has benefitted them for a long time. Breeding and eating animals is a very long-standing cultural institution that is a mutually beneficial relationship between human beings and animals. We bring animals into existence, care for them, rear them, and then kill and eat them. From this, we get food and other animal products, and they get life. Both sides benefit. I should say that by ‘animals’ here, I mean nonhuman animals. It is true that we are also animals, but we are also more than that, in a way that makes a difference.

If you care about animals, you should eat them. It is not just that you may do so, but you should do so. In fact, you owe it to animals to eat them. It is your duty. Why? Because eating animals benefits them and has benefitted them for a long time. Breeding and eating animals is a very long-standing cultural institution that is a mutually beneficial relationship between human beings and animals. We bring animals into existence, care for them, rear them, and then kill and eat them. From this, we get food and other animal products, and they get life. Both sides benefit. I should say that by ‘animals’ here, I mean nonhuman animals. It is true that we are also animals, but we are also more than that, in a way that makes a difference.

It is true that the practice does not benefit an animal at the moment we eat it. The benefit to the animal on our dinner table lies in the past. Nevertheless, even at that point, it has benefitted by its destiny of being killed and eaten.

More here.

Joanna Lumley, one of the judges the year it won, found the book ‘indefensible’. Decades later, Booker winner

Joanna Lumley, one of the judges the year it won, found the book ‘indefensible’. Decades later, Booker winner  The idea that polarization is the predominant ailment of American democracy looms large in political commentary. It is asserted across the partisan spectrum, taking center stage in President Biden’s Inaugural Address and in recent statements by former Presidents Bush and Carter. The diagnosis resonates with voters as well. Though pronounced in the US, polarization isn’t strictly America’s problem. The UK remains significantly divided over Brexit, and one in five French voters identifies as “extreme.” A pair of researchers has called polarization the new specter haunting Europe. Another team says it is a “global crisis.”

The idea that polarization is the predominant ailment of American democracy looms large in political commentary. It is asserted across the partisan spectrum, taking center stage in President Biden’s Inaugural Address and in recent statements by former Presidents Bush and Carter. The diagnosis resonates with voters as well. Though pronounced in the US, polarization isn’t strictly America’s problem. The UK remains significantly divided over Brexit, and one in five French voters identifies as “extreme.” A pair of researchers has called polarization the new specter haunting Europe. Another team says it is a “global crisis.” The Ulysses centenary is a momentous occasion. It is an event for celebration, but one that prompts the question of what exactly is to be celebrated. The publication of an extraordinary Irish novel? Perhaps, but what precisely is Ulysses’s relationship to the Irish novel tradition that preceded or has followed it? The publication of a work that transformed the inherited form of the novel more generally? Certainly, Ulysses revolutionised the modern novel as form but what sort of revolution did it enact and what was its later issue? How do aesthetic revolutions relate to sociopolitical revolutions? Do they, like the latter, have their radical springtimes and then become autumnally institutionalised and conservative? Or must they each be assessed on quite different terms? That Ulysses was an event nearly everyone will agree. However, can we say even now, a century later, what kind of event it really was in Irish or world literary terms? And is Ulysses really a novel at all in any case?

The Ulysses centenary is a momentous occasion. It is an event for celebration, but one that prompts the question of what exactly is to be celebrated. The publication of an extraordinary Irish novel? Perhaps, but what precisely is Ulysses’s relationship to the Irish novel tradition that preceded or has followed it? The publication of a work that transformed the inherited form of the novel more generally? Certainly, Ulysses revolutionised the modern novel as form but what sort of revolution did it enact and what was its later issue? How do aesthetic revolutions relate to sociopolitical revolutions? Do they, like the latter, have their radical springtimes and then become autumnally institutionalised and conservative? Or must they each be assessed on quite different terms? That Ulysses was an event nearly everyone will agree. However, can we say even now, a century later, what kind of event it really was in Irish or world literary terms? And is Ulysses really a novel at all in any case? In the spring of 1953, a former Nazi named Anton Melchers, who in the Third Reich had been a newspaper editor, war reporter, and—according to his brother—talented propagandist, was admitted to the university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg. His brother, a former high-ranking SS officer, brought him there because Melchers had stopped eating. At the clinic, Melchers reported hearing voices that accused him of sexual immorality and intimated that he would be “paraded” in the streets. Melchers was also preoccupied, his brother said, with anxieties about being “rounded up and taken away” as punishment for his National Socialist past.

In the spring of 1953, a former Nazi named Anton Melchers, who in the Third Reich had been a newspaper editor, war reporter, and—according to his brother—talented propagandist, was admitted to the university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg. His brother, a former high-ranking SS officer, brought him there because Melchers had stopped eating. At the clinic, Melchers reported hearing voices that accused him of sexual immorality and intimated that he would be “paraded” in the streets. Melchers was also preoccupied, his brother said, with anxieties about being “rounded up and taken away” as punishment for his National Socialist past.

In 1152, a curious scene unfolded outside the

In 1152, a curious scene unfolded outside the  The phrase “black lives matter” was born in July of 2013, in a Facebook post by Alicia Garza, called “a love letter to black people.” The post was intended as an affirmation for a community distraught over George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the shooting death of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida. Garza, now thirty-five, is the special-projects director in the Oakland office of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which represents twenty thousand caregivers and housekeepers, and lobbies for labor legislation on their behalf. She is also an advocate for queer and transgender rights and for anti-police-brutality campaigns.

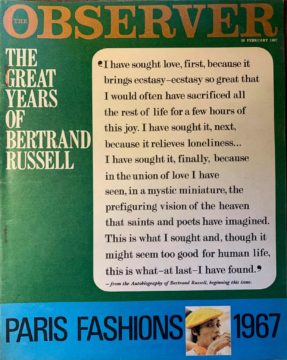

The phrase “black lives matter” was born in July of 2013, in a Facebook post by Alicia Garza, called “a love letter to black people.” The post was intended as an affirmation for a community distraught over George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the shooting death of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida. Garza, now thirty-five, is the special-projects director in the Oakland office of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which represents twenty thousand caregivers and housekeepers, and lobbies for labor legislation on their behalf. She is also an advocate for queer and transgender rights and for anti-police-brutality campaigns. The Observer Magazine has never again featured an extract from the autobiography of a philosopher on its cover after ‘The Great Years of Bertrand Russell’, 26 February 1967.

The Observer Magazine has never again featured an extract from the autobiography of a philosopher on its cover after ‘The Great Years of Bertrand Russell’, 26 February 1967. New high-speed cellphone services have raised concerns of interference with aircraft operations, particularly as aircraft are landing at airports. The Federal Aviation Administration has

New high-speed cellphone services have raised concerns of interference with aircraft operations, particularly as aircraft are landing at airports. The Federal Aviation Administration has  Every few days, there’s another article pointing out the likelihood that a Democratic win[1] in the 2024 US election will be overturned, and suggesting various ways it might be prevented, none of which seem very likely to work. The best hope would seem to be a crushing Democratic victory in the 2022 midterms, which doesn’t look likely right now[2]

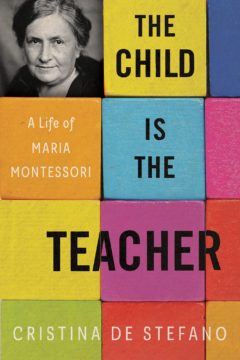

Every few days, there’s another article pointing out the likelihood that a Democratic win[1] in the 2024 US election will be overturned, and suggesting various ways it might be prevented, none of which seem very likely to work. The best hope would seem to be a crushing Democratic victory in the 2022 midterms, which doesn’t look likely right now[2] She hires the daughter of a custodian to teach kindergarten. It is 1907 in a poor neighborhood in Rome, where there has never been a kindergarten before. An agency tasked with improving neighborhoods in the city is trying to provide a place for children to go while their parents are working, and Maria Montessori has been asked to run the program. Montessori instructs the inexperienced teacher that the children should be allowed to lie on the floor or sit under the table—to do whatever they want. Observe them closely and tell me what you notice, she says. The new teacher reports back: the children are more interested in helping her sweep than in playing with the donated toys. Montessori writes this down. One day when Montessori is on her way to the classroom, she notices a peaceful baby girl with her mother in the courtyard. She invites them in and challenges the young children to be as quiet as the baby. This goes well. Montessori decides to make a ritual out of it: a period of silence for the children, one that ends when each child is called by name into the next room. This, also, the children love. The practice is adopted.

She hires the daughter of a custodian to teach kindergarten. It is 1907 in a poor neighborhood in Rome, where there has never been a kindergarten before. An agency tasked with improving neighborhoods in the city is trying to provide a place for children to go while their parents are working, and Maria Montessori has been asked to run the program. Montessori instructs the inexperienced teacher that the children should be allowed to lie on the floor or sit under the table—to do whatever they want. Observe them closely and tell me what you notice, she says. The new teacher reports back: the children are more interested in helping her sweep than in playing with the donated toys. Montessori writes this down. One day when Montessori is on her way to the classroom, she notices a peaceful baby girl with her mother in the courtyard. She invites them in and challenges the young children to be as quiet as the baby. This goes well. Montessori decides to make a ritual out of it: a period of silence for the children, one that ends when each child is called by name into the next room. This, also, the children love. The practice is adopted. The essays in Extinct often answer two questions: What was it that has disappeared and why? And then, what was the significance of this loss? Some, like Slessor’s, are lucidly personal meditations, stuffed with anecdotes and design history; others are more technical treatises on the reason a particular technology failed to take root. The editors identify six general reasons why things become extinct and categorize each object in this way. Certain objects are deemed “failed”; they simply didn’t work. Many more, though, are “superseded” by more advanced models of similar things. Some dead objects, especially commercial products, are “defunct”—these have failed to gain widespread adoption, or couldn’t be mass-produced, or have simply gone out of style. Others are “aestivated,” meaning that they disappear but are revived in a new form. Still others are classified as “visionary,” in that they never quite came into being at all. The rest are “enforced,” basically regulated into disappearance.

The essays in Extinct often answer two questions: What was it that has disappeared and why? And then, what was the significance of this loss? Some, like Slessor’s, are lucidly personal meditations, stuffed with anecdotes and design history; others are more technical treatises on the reason a particular technology failed to take root. The editors identify six general reasons why things become extinct and categorize each object in this way. Certain objects are deemed “failed”; they simply didn’t work. Many more, though, are “superseded” by more advanced models of similar things. Some dead objects, especially commercial products, are “defunct”—these have failed to gain widespread adoption, or couldn’t be mass-produced, or have simply gone out of style. Others are “aestivated,” meaning that they disappear but are revived in a new form. Still others are classified as “visionary,” in that they never quite came into being at all. The rest are “enforced,” basically regulated into disappearance. When Oscar Wilde left prison in 1897, shocked observers saw how a two-year sentence with hard labour for gross indecency had prematurely aged the Irish playwright. Shunned by London society and ostracized by his family, he died penniless in Paris three years later, aged 46. Had the scientific field of human ageing

When Oscar Wilde left prison in 1897, shocked observers saw how a two-year sentence with hard labour for gross indecency had prematurely aged the Irish playwright. Shunned by London society and ostracized by his family, he died penniless in Paris three years later, aged 46. Had the scientific field of human ageing  F

F