Karin Wulf in Smithsonian:

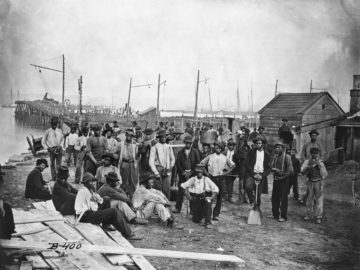

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or the first incidence of slavery in North America, was widely recognized as inaugurating race-based slavery in the British colonies that would become the United States.

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or the first incidence of slavery in North America, was widely recognized as inaugurating race-based slavery in the British colonies that would become the United States.

That 400th anniversary is the occasion for a unique collaboration: Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019, edited by historians Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. Kendi and Blain brought together 90 black writers—historians, scholars of other fields, journalists, activists and poets—to cover the full sweep and extraordinary diversity of those 400 years of black history. Although its scope is encyclopedic, the book is anything but a dry, dispassionate march through history. It’s elegantly structured in ten 40-year sections composed of eight essays (each covering one theme in a five-year period) and a poem punctuating the section conclusion; Kendi calls Four Hundred Souls “a chorus.”

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

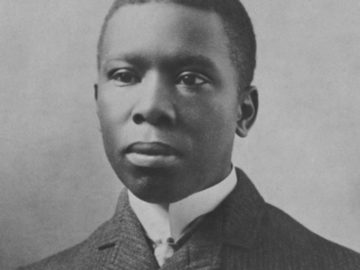

“Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery.

“Suppose the only Negro who survived some centuries hence was the Negro painted by white Americans in the novels and essays they have written. What would people in a hundred years say of black Americans?” This is the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his lecture “Criteria of Negro Art.” The remarks were made at the 1926 NAACP annual meeting in Chicago and later published as part of a multi-issue series titled “The Negro in Art” in The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine. Du Bois gave the speech at a ceremony honoring the contributions of the eminent author, editor, and historian Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had made it his life’s work to document the positive cultural, social, and political contributions black Americans had made to the development of the United States. He did so in an effort to combat the empty but popular rhetoric of those who suggested that black people had no history, no culture, and had nothing to add to the country beyond the labor of their bodies. That same year, Woodson developed Negro History Week, the precursor to what would eventually become Black History Month, an extension of his effort to illuminate black contributions to the American project. And while Du Bois sought to honor Woodson in his remarks, he also used the opportunity to espouse his own beliefs regarding the role and importance of black artists as America wrestled with the evolution of white supremacy only a generation after the end of slavery. I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD

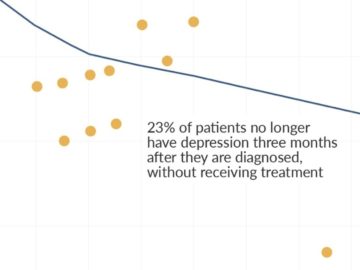

I HAVE RECENTLY REREAD In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings.

In order to tackle the world’s largest problems, we need to be able to identify their causes and effective ways to solve them. How would we know about the effects of a new idea, treatment or policy? Answering this question can be difficult. Some research is poorly done and there are incentives for scientists and funders to exaggerate their findings. In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions.

In The Tragedy of Macbeth, long-time Hollywood presence Joel Coen — who has 18 prior films to his credit — takes sole creative control of a project for the first time. The result, not unlike the tale of Macbeth itself, is a tragedy of epic proportions. After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.”

After her death in May 1944, the painter, poet, and designer Florine Stettheimer was eulogized by fellow painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Although the two were not always on warm terms, no other female artist in the United States equaled Stettheimer for originality, sense of color, or national renown. Indeed, given that there were so few female artists in New York City—or in the United States—who made significant work during the 1920s and ’30s, O’Keeffe was both a fitting and perhaps necessary choice. However, if the orator was predictable, the speech was not. Unlike many eulogies that tend toward glossy retrospection, O’Keeffe’s remarks were purposeful and pointed. This was an opportunity to speak candidly about matters Stettheimer herself might not have expressed so directly. “Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation,” O’Keeffe said. “[She] put into visible form … a way of life that is going and cannot happen again, something that has been alive in our city.” Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Awkwardly for today’s secular progressives, opposition to eugenics during its heyday in the West came almost exclusively from religious sources, particularly the Catholic Church. Eugenic ideas were disseminated everywhere, but few Catholic countries applied them. The only involuntary sterilisation legislation in Latin America was enacted in the state of Veracruz in Mexico in 1932. In Catholic Europe, Spain, Portugal and Italy passed no eugenic laws. By contrast, Norway and Sweden legalised eugenic sterilisation in 1934 and 1935, with Sweden requiring the consent of those sterilised only in 1976. In the US, more than 70,000 people were forcibly sterilised during the 20th century, with sterilisation without the inmates’ consent being reported in female prisons in California up to 2014.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements.

Salwa Sebti was growing impatient. In 2014, she and her colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas had begun tracking mice that had a genetically enhanced ability to detoxify their cells. The goal was to test the anti-ageing effects of boosting autophagy, the biological housekeeping process by which cells rid themselves of damaged components. But it was almost two years — a timespan roughly equivalent to 70 years in humans — before the mice showed any clear signs of health improvements. Of constant fascination for me are the ways in which literature employs skin color to reveal character or drive narrative—especially if the fictional main character is white (which is almost always the case). Whether it is the horror of one drop of the mystical “black” blood, or signs of innate white superiority, or of deranged and excessive sexual power, the framing and the meaning of color are often the deciding factors. For the horror that the “one-drop” rule excites, there is no better guide than William Faulkner. What else haunts “The Sound and the Fury” or “Absalom, Absalom!”? Between the marital outrages incest and miscegenation, the latter (an old but useful term for “the mixing of races”) is obviously the more abhorrent. In much American literature, when plot requires a family crisis, nothing is more disgusting than mutual sexual congress between the races. It is the mutual aspect of these encounters that is rendered shocking, illegal, and repulsive. Unlike the rape of slaves, human choice or, God forbid, love receives wholesale condemnation. And for Faulkner they lead to murder.

Of constant fascination for me are the ways in which literature employs skin color to reveal character or drive narrative—especially if the fictional main character is white (which is almost always the case). Whether it is the horror of one drop of the mystical “black” blood, or signs of innate white superiority, or of deranged and excessive sexual power, the framing and the meaning of color are often the deciding factors. For the horror that the “one-drop” rule excites, there is no better guide than William Faulkner. What else haunts “The Sound and the Fury” or “Absalom, Absalom!”? Between the marital outrages incest and miscegenation, the latter (an old but useful term for “the mixing of races”) is obviously the more abhorrent. In much American literature, when plot requires a family crisis, nothing is more disgusting than mutual sexual congress between the races. It is the mutual aspect of these encounters that is rendered shocking, illegal, and repulsive. Unlike the rape of slaves, human choice or, God forbid, love receives wholesale condemnation. And for Faulkner they lead to murder. IN MAY OF 2012

IN MAY OF 2012 Many of Robinson’s twenty-one science-fiction novels are ecological in theme, and this coming summer he will publish “

Many of Robinson’s twenty-one science-fiction novels are ecological in theme, and this coming summer he will publish “ What the face mask is to American society, the essay is to American literature: deceptively slight, heroically versatile, centuries old but lately a subject of great interest — not because it’s doing anything new, but because everything else is falling apart.

What the face mask is to American society, the essay is to American literature: deceptively slight, heroically versatile, centuries old but lately a subject of great interest — not because it’s doing anything new, but because everything else is falling apart. A great deal of public discussion in recent weeks has suggested that “endemicity”—a state where the virus continues to circulate in the population like scores of other respiratory viruses, with more predictability albeit probably still with seasonal surges—is around the corner. The Europe office of the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently stated that the continent may be entering the “

A great deal of public discussion in recent weeks has suggested that “endemicity”—a state where the virus continues to circulate in the population like scores of other respiratory viruses, with more predictability albeit probably still with seasonal surges—is around the corner. The Europe office of the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, recently stated that the continent may be entering the “ During the first pandemic lockdowns, thousands of vivid dreams were suddenly shared across the internet and among friends. Though some of them had to do directly with COVID, many were simply intense and mysterious, in the way dreams often are. Yet for some reason, people felt newly impelled to convey them to others. The dreams were soon compiled into databases, written up in newspaper articles, and eventually integrated into scientific studies. This phenomenon may turn out to be a significant event in the history of the social imagination. For thousands of years, and in many cultures, talking about dreams has been considered hugely important. But in modernity, dreams have been regularly denigrated. In the mainstream, at least, they have been written off as superstitious, flighty, or boring. Then suddenly, in the pandemic, a great mass of people, mobilized across the internet, felt (at least for a few months) otherwise. There has probably never been such a sudden and expansive efflorescence of public dream sharing in modern history.

During the first pandemic lockdowns, thousands of vivid dreams were suddenly shared across the internet and among friends. Though some of them had to do directly with COVID, many were simply intense and mysterious, in the way dreams often are. Yet for some reason, people felt newly impelled to convey them to others. The dreams were soon compiled into databases, written up in newspaper articles, and eventually integrated into scientific studies. This phenomenon may turn out to be a significant event in the history of the social imagination. For thousands of years, and in many cultures, talking about dreams has been considered hugely important. But in modernity, dreams have been regularly denigrated. In the mainstream, at least, they have been written off as superstitious, flighty, or boring. Then suddenly, in the pandemic, a great mass of people, mobilized across the internet, felt (at least for a few months) otherwise. There has probably never been such a sudden and expansive efflorescence of public dream sharing in modern history.