Kathleen Wallace in Aeon:

Many philosophers, at least in the West, have sought to identify the invariable or essential conditions of being a self. A widely taken approach is what’s known as a psychological continuity view of the self, where the self is a consciousness with self-awareness and personal memories. Sometimes these approaches frame the self as a combination of mind and body, as René Descartes did, or as primarily or solely consciousness. John Locke’s prince/pauper thought experiment, wherein a prince’s consciousness and all his memories are transferred into the body of a cobbler, is an illustration of the idea that personhood goes with consciousness. Philosophers have devised numerous subsequent thought experiments – involving personality transfers, split brains and teleporters – to explore the psychological approach. Contemporary philosophers in the ‘animalist’ camp are critical of the psychological approach, and argue that selves are essentially human biological organisms. (Aristotle might also be closer to this approach than to the purely psychological.) Both psychological and animalist approaches are ‘container’ frameworks, positing the body as a container of psychological functions or the bounded location of bodily functions.

Many philosophers, at least in the West, have sought to identify the invariable or essential conditions of being a self. A widely taken approach is what’s known as a psychological continuity view of the self, where the self is a consciousness with self-awareness and personal memories. Sometimes these approaches frame the self as a combination of mind and body, as René Descartes did, or as primarily or solely consciousness. John Locke’s prince/pauper thought experiment, wherein a prince’s consciousness and all his memories are transferred into the body of a cobbler, is an illustration of the idea that personhood goes with consciousness. Philosophers have devised numerous subsequent thought experiments – involving personality transfers, split brains and teleporters – to explore the psychological approach. Contemporary philosophers in the ‘animalist’ camp are critical of the psychological approach, and argue that selves are essentially human biological organisms. (Aristotle might also be closer to this approach than to the purely psychological.) Both psychological and animalist approaches are ‘container’ frameworks, positing the body as a container of psychological functions or the bounded location of bodily functions.

All these approaches reflect philosophers’ concern to focus on what the distinguishing or definitional characteristic of a self is, the thing that will pick out a self and nothing else, and that will identify selves as selves, regardless of their particular differences.

More here.

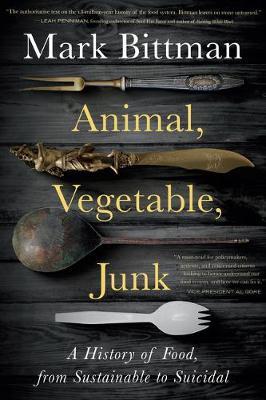

From his magnum opus, How to Cook Everything, and its many cookbook companions, to his recipes for The New York Times, to his essays on food policy, Bittman has developed a breeziness that masks the weight of the politics and economics that surround the making and consuming of food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, his latest book, he offers us his most thoroughgoing attack on the corporate forces that govern our food, tracking the evolution of cultivation and consumption from primordial to modern times and developing what is arguably his most radical and forthright argument yet about how to address our contemporary food cultures’ many ills. But it still goes down easy; the broccoli tastes good enough that you’ll happily go for seconds.

From his magnum opus, How to Cook Everything, and its many cookbook companions, to his recipes for The New York Times, to his essays on food policy, Bittman has developed a breeziness that masks the weight of the politics and economics that surround the making and consuming of food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, his latest book, he offers us his most thoroughgoing attack on the corporate forces that govern our food, tracking the evolution of cultivation and consumption from primordial to modern times and developing what is arguably his most radical and forthright argument yet about how to address our contemporary food cultures’ many ills. But it still goes down easy; the broccoli tastes good enough that you’ll happily go for seconds. When Shashank Yadav took to Twitter to plead for oxygen to save his dying grandfather

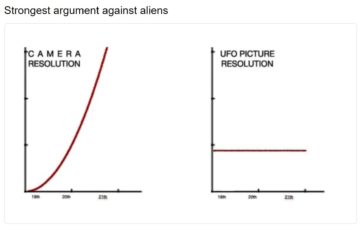

When Shashank Yadav took to Twitter to plead for oxygen to save his dying grandfather  The idea of UFOs has gone mainstream. The dam broke with a New York Times story about a year ago on

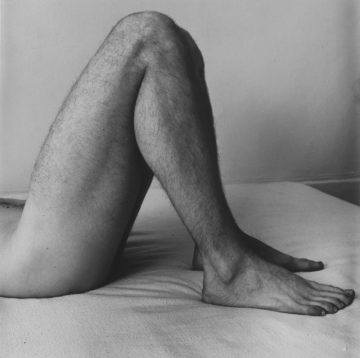

The idea of UFOs has gone mainstream. The dam broke with a New York Times story about a year ago on  “How to describe the effect of these photographs?” writes Moyra Davey on the pictures that the late American artist Peter Hujar took of the Hudson River in 1976. “The water seems embodied, we see faces—eyes and lips—and liquid takes on a velvety smoothness and viscosity that could almost be a solid. Each image seems to have its own personality, and we sense Hujar’s presence as well, a man standing on a pier, with all the connotations of that locale, looking out and taking in the river at his feet. I wonder if he knew when he took the pictures that the resulting images would be so sensual, so corporeal and unearthly at the same time.” Davey writes these words at the end of The Shabbiness of Beauty, a newly published photobook, in which she delves into the image-archives of Hujar and edits his photographs into a new series together with her own.

“How to describe the effect of these photographs?” writes Moyra Davey on the pictures that the late American artist Peter Hujar took of the Hudson River in 1976. “The water seems embodied, we see faces—eyes and lips—and liquid takes on a velvety smoothness and viscosity that could almost be a solid. Each image seems to have its own personality, and we sense Hujar’s presence as well, a man standing on a pier, with all the connotations of that locale, looking out and taking in the river at his feet. I wonder if he knew when he took the pictures that the resulting images would be so sensual, so corporeal and unearthly at the same time.” Davey writes these words at the end of The Shabbiness of Beauty, a newly published photobook, in which she delves into the image-archives of Hujar and edits his photographs into a new series together with her own. W

W I have always been very moved by pictures about slaughterhouses and meat,” the painter Francis Bacon said to an interviewer in 1962. He regarded meat with fellow-feeling. “If I go into a butcher’s shop, I always think it’s surprising that I wasn’t there instead of the animal,” he later said. We have a photograph of him gazing serenely out at us from between two sides of beef. Cloven carcasses—indeed, piles of miscellaneous innards—recur in his paintings. Basically, he liked whatever was inside, as opposed to outside, the skin.

I have always been very moved by pictures about slaughterhouses and meat,” the painter Francis Bacon said to an interviewer in 1962. He regarded meat with fellow-feeling. “If I go into a butcher’s shop, I always think it’s surprising that I wasn’t there instead of the animal,” he later said. We have a photograph of him gazing serenely out at us from between two sides of beef. Cloven carcasses—indeed, piles of miscellaneous innards—recur in his paintings. Basically, he liked whatever was inside, as opposed to outside, the skin. Dana El Kurd in Sidecar:

Dana El Kurd in Sidecar: Ted Fertik (he/him) in Alchemist:

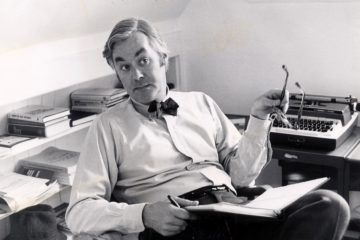

Ted Fertik (he/him) in Alchemist: George Scialabba in The Baffler:

George Scialabba in The Baffler:

“The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society,” Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York said during a lecture at Harvard in 1986. “The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.” Moynihan, an apostle of complexity, lived at the intersection of those two truths, a place where he was free to become one of the most creative American thinkers of the late 20th century. He sensed, and then came to know, that the social problems of what was being called “postindustrial” society would be different from those that came before. He identified these problems, sometimes controversially. In so doing, he predicted the dislocations of the 21st century with uncanny accuracy. He did it with elegance and wit and — this may be a surprise — transcendent humility. His spot-on sense of what truly mattered deserves to be revisited now, if we’re to grope our way past the mess we’ve become as a society.

“The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society,” Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York said during a lecture at Harvard in 1986. “The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.” Moynihan, an apostle of complexity, lived at the intersection of those two truths, a place where he was free to become one of the most creative American thinkers of the late 20th century. He sensed, and then came to know, that the social problems of what was being called “postindustrial” society would be different from those that came before. He identified these problems, sometimes controversially. In so doing, he predicted the dislocations of the 21st century with uncanny accuracy. He did it with elegance and wit and — this may be a surprise — transcendent humility. His spot-on sense of what truly mattered deserves to be revisited now, if we’re to grope our way past the mess we’ve become as a society.