Rana Mitter and Elsbeth Johnson in the Harvard Business Review:

When we first traveled to China, in the early 1990s, it was very different from what we see today. Even in Beijing many people wore Mao suits and cycled everywhere; only senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials used cars. In the countryside life retained many of its traditional elements. But over the next 30 years, thanks to policies aimed at developing the economy and increasing capital investment, China emerged as a global power, with the second-largest economy in the world and a burgeoning middle class eager to spend.

When we first traveled to China, in the early 1990s, it was very different from what we see today. Even in Beijing many people wore Mao suits and cycled everywhere; only senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials used cars. In the countryside life retained many of its traditional elements. But over the next 30 years, thanks to policies aimed at developing the economy and increasing capital investment, China emerged as a global power, with the second-largest economy in the world and a burgeoning middle class eager to spend.

One thing hasn’t changed, though: Many Western politicians and business executives still don’t get China. Believing, for example, that political freedom would follow the new economic freedoms, they wrongly assumed that China’s internet would be similar to the freewheeling and often politically disruptive version developed in the West. And believing that China’s economic growth would have to be built on the same foundations as those in the West, many failed to envisage the Chinese state’s continuing role as investor, regulator, and intellectual property owner.

Why do leaders in the West persist in getting China so wrong?

More here.

Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members.

Along with fish, aluminium and Björk, Eve Online is one of Iceland’s biggest exports. Launched in 2003, it is a science-fiction project of unprecedented scale and ambition. It presents a cosmos of 7,500 interconnected star systems, known as New Eden, which can be travelled in spaceships built and flown by any individual. In-game professions vary. There are miners, traders, pirates, journalists and educators. You are free to work alone or in loose-knit corporations and alliances, the largest of which are comprised of tens of thousands of members. The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures.

The American Land Museum is a network of landscape exhibition sites being developed across the United States by the Center for Land Use Interpretation and other agencies. The purpose of the museum is to create a dynamic contemporary portrait of the nation, a portrait composed of the national landscape itself. Selected exhibition locations represent regional land use patterns, themes, and development issues. Within each exhibit location are a number of specified experiential zones with collections of material artifacts in the landscape, landmarks selected from among the field of existing structures. Reading Battles in the Desert, one will note the special magic of Pacheco’s writing — that simplicity, so deceptive and so masterful. The narrative voice is a well-calibrated device gliding through the reality of things, stories, and emotions, always giving the impression that memory never betrays. “Pacheco’s craft and mastery make writing look easy,” writes Luis Jorge Boone in “José Emilio Pacheco: Un lector fuera del tiempo” (“José Emilio Pacheco: a reader outside of time”), an essay on the author’s work. “Achieving that almost magical ease took Pacheco years of rewrites, edits, cuts. The layers upon layers of work the author put into his books over the years is legendary.”

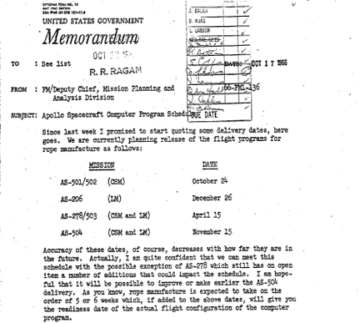

Reading Battles in the Desert, one will note the special magic of Pacheco’s writing — that simplicity, so deceptive and so masterful. The narrative voice is a well-calibrated device gliding through the reality of things, stories, and emotions, always giving the impression that memory never betrays. “Pacheco’s craft and mastery make writing look easy,” writes Luis Jorge Boone in “José Emilio Pacheco: Un lector fuera del tiempo” (“José Emilio Pacheco: a reader outside of time”), an essay on the author’s work. “Achieving that almost magical ease took Pacheco years of rewrites, edits, cuts. The layers upon layers of work the author put into his books over the years is legendary.” During the final weeks of the Trump Administration, a senior official on the National Security Council sat at his desk in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, across from the West Wing, on the White House grounds. It was mid-November, and he had recently returned from a work trip abroad. At the end of the day, he left the building and headed toward his car, which was parked a few hundred yards away, along the Ellipse, between the White House and the Washington Monument. As he walked, he began to hear a ringing in his ears. His body went numb, and he had trouble controlling the movement of his legs and his fingers. Trying to speak to a passerby, he had difficulty forming words. “It came on very suddenly,” the official recalled later, while describing the experience to a colleague. “In a matter of about seven minutes, I went from feeling completely fine to thinking, Oh, something’s not right, to being very, very worried and actually thinking I was going to die.”

During the final weeks of the Trump Administration, a senior official on the National Security Council sat at his desk in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, across from the West Wing, on the White House grounds. It was mid-November, and he had recently returned from a work trip abroad. At the end of the day, he left the building and headed toward his car, which was parked a few hundred yards away, along the Ellipse, between the White House and the Washington Monument. As he walked, he began to hear a ringing in his ears. His body went numb, and he had trouble controlling the movement of his legs and his fingers. Trying to speak to a passerby, he had difficulty forming words. “It came on very suddenly,” the official recalled later, while describing the experience to a colleague. “In a matter of about seven minutes, I went from feeling completely fine to thinking, Oh, something’s not right, to being very, very worried and actually thinking I was going to die.” I

I

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.

Shada Safadi. Promises. 2014.

Shada Safadi. Promises. 2014. The overwhelming majority of pre-service and in-service teachers I have worked with over the past two decades believe that they should, first and foremost, love, care, and nurture their students. Everything else associated with what is euphemistically called “best practice,” they believe, will follow. When pushed to describe what loving, caring and nurturing their students actually looks like within and beyond the classroom and school—in theory and practice—many of them have trouble getting beyond superficial appeals to “multiple intelligences,” “diversity,” “safe spaces,” and “culturally responsive pedagogy.” Focused primarily on making their students feel safe and emotionally supported, they’ve reduced their pedagogical responsibilities to a metaphorical big hug. Stir in a tablespoon of standardized ideological content, blend with a half cup of research-based strategies, add a pinch of job training/college prep, stir in a few high-stakes tests and, voilà, the neoliberal agenda for public education is rationalized and set.

The overwhelming majority of pre-service and in-service teachers I have worked with over the past two decades believe that they should, first and foremost, love, care, and nurture their students. Everything else associated with what is euphemistically called “best practice,” they believe, will follow. When pushed to describe what loving, caring and nurturing their students actually looks like within and beyond the classroom and school—in theory and practice—many of them have trouble getting beyond superficial appeals to “multiple intelligences,” “diversity,” “safe spaces,” and “culturally responsive pedagogy.” Focused primarily on making their students feel safe and emotionally supported, they’ve reduced their pedagogical responsibilities to a metaphorical big hug. Stir in a tablespoon of standardized ideological content, blend with a half cup of research-based strategies, add a pinch of job training/college prep, stir in a few high-stakes tests and, voilà, the neoliberal agenda for public education is rationalized and set.

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.

Aye Chan Zin, a 22 year old competitive cyclist, once raced from Yangon to Mandalay and back. He fell and lost both incisors to gold teeth.