Morgan Meis at Slant Books:

It is startling and more than a little amusing to finally realize, or to have pointed out to you, as happened to me, that the word ‘dunce’, a not exactly au courant but certainly still, I think, recognizable word that basically means stupid, one who wears the dunce cap, that this word is, actually, a shortened form of saying that a person is like Duns Scotus, the medieval scholastic philosopher and member of the Franciscan order. Calling someone a dunce is calling them a Duns, a Scotist. Why one of the great minds of Western philosophy and theology would have become synonymous with stupidity is not immediately apparent. Something must have gone awry here.

In fact, the trajectory of word and meaning is not so hard to understand once one parses it out. Medieval Scholasticism, of which Duns Scotus was a great luminary, fell out of favor. Scotus’ once admired feats of logical daring began to look empty and pointless. Add to that the Protestant attack on the doctrines of the Church that Scotus did so much to defend intellectually and you get to the point where a person who was once called doctor subtilis, The Subtle Doctor, is now openly referred to as a dumb ass.

The question, though, and this is something I am still in the process of thinking through and which would require, I fear, rather too much reading of abstruse and difficult to love medieval works of philosophy, a task to which I devoted some time as a younger person studying philosophy while, at the same time, trying to bone up my medieval Latin, to varying degrees of success I should add, though I did get through quite a bit of Scotus’ work unraveling a couple of the trickier problems in what Aristotle means, exactly, by the words ‘being’ and ‘essence’.

More here.

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke.

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke. President

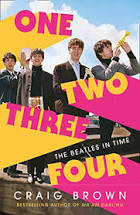

President  Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story.

Wait, not another book about the Beatles? Surely that story’s bones have been picked clean by now? What saves One Two Three Four from being just another Beatles indulgathon is how the author has reworked the standard biography template. His take is a seductive miscellany of essays, insider accounts, opinions, flight-of-fancy yarns, and more. Much of it is sourced from already published material but Brown also includes his own opinions and anecdotes. Somehow he has managed to create a uniquely fresh perceptive on a well-worn story. “FILING FOR DIVORCE,”

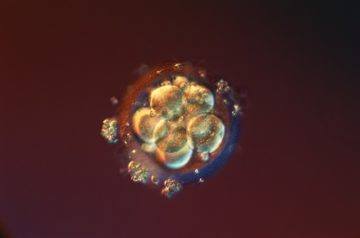

“FILING FOR DIVORCE,”  The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped.

The international body representing stem-cell scientists has torn up a decades-old limit on the length of time that scientists should grow human embryos in the lab, giving more leeway to researchers who are studying human development and disease. Previously, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommended that scientists culture human embryos for no more than two weeks after fertilization. But on 26 May, the society said it was relaxing this famous limit, known as the ‘14-day rule’. Rather than replace or extend the limit, the ISSCR now suggests that studies proposing to grow human embryos beyond the two-week mark be considered on a case-by-case basis, and be subjected to several phases of review to determine at what point the experiments must be stopped. George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

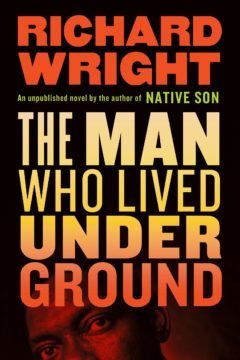

George Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stewart Mill, and even pre-empted elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick. A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s.

A surrealist and existentialist tale, The Man Who Lived Underground was rejected by several publishers, but the novel found an afterlife via a series of winding roads. The rejections led Wright to condense the narrative, in particular cutting the lengthy description of police violence in the novel’s opening, and turn it into a short story that was published in 1944. That story was admired by Wright’s friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison. Later, after winning the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, Ellison stated that his novel had been inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. While he and Wright had fallen out by this time, Wright’s influence on the novel was hard to deny. Despite this fact, Invisible Man entered the American literary canon, while Wright’s story languished in obscurity. In the popular imagination, he became known as the author of Native Son, Black Boy, and (for those interested in anti-colonialism) The Color Curtain, but not as the originator of invisible men living underground. That honor remained Ellison’s. I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think.

I am going to try to account for the reasons painters have consistently felt it OK to take note of the critiques aimed at the validity of their art form but almost always dismiss them in practice. A lot of what I have to say here is well-known in the mainly unspoken way things can get well-known. So I am trying to spell out what I think many people already know, and what I believe most painters do think. One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

One day last August, as they struggled to figure out whether to lift Covid-19 restrictions, the supervisors of Placer County, California, convened a panel of experts. It was a reasonable move. If being a local official could be thankless in normal times, the pandemic had made it nearly impossible. Federal messaging had been hopelessly muddled. Rules meant to stop viral spread came with painful side effects. One constituent insisted the sheriff enforce lockdowns; another called stay-at-home-orders an economic death sentence. Wanting advice from doctors and professors was hardly surprising.

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace.

For decades, the Democratic Party has stood by Israel in times of war and peace. I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song.

I believe that the books and stories we fall in love with make us who we are, or, not to claim too much, the beloved tale becomes a part of the way in which we understand things and make judgments and choices in our daily lives. A book may cease to speak to us as we grow older, and our feeling for it will fade. Or we may suddenly, as our lives shape and hopefully increase our understanding, be able to appreciate a book we dismissed earlier; we may suddenly be able to hear its music, to be enraptured by its song. Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician

Democracy posits the radical idea that political power and legitimacy should ultimately be found in all of the people, rather than a small group of experts or for that matter arbitrarily-chosen hereditary dynasties. Nevertheless, a good case can be made that the bottom-up and experimental nature of democracy actually makes for better problem-solving in the political arena than other systems. Political theorist Henry Farrell (in collaboration with statistician